A Different Beginning

Nadya Matish has always known she was born from a sperm donor. Because she has two moms, Matish was born through artificial insemination: the process of conceiving a baby without sexual intercourse.

Matish’s parents used a donation from a man who chose to remain anonymous. Because of his anonymity, Matish refers to her biological father as simply ‘the donor’.

“My family refers to the donor to explain our unexplainable physical traits,” Matish said. “Me and my sister have very short thumbs, and we sometimes joke about how we must have gotten the donor’s “stubby thumb”, because neither of our moms have short thumbs like we do.”

In the use of a sperm bank, the donor’s identity typically remains anonymous to the families who use their donations. Some people have eventually unearthed the identities of their donors, but this event has yet to come to fruition for Matish and her sister. Aside from a sheet of his medical history that her parents received upon their purchase of the sperm, Matish knows no personal information about him.

“I honestly don’t really want to know who he is,” Matish said. “He doesn’t carry any emotional weight in my mind, because he’s not my parent.”

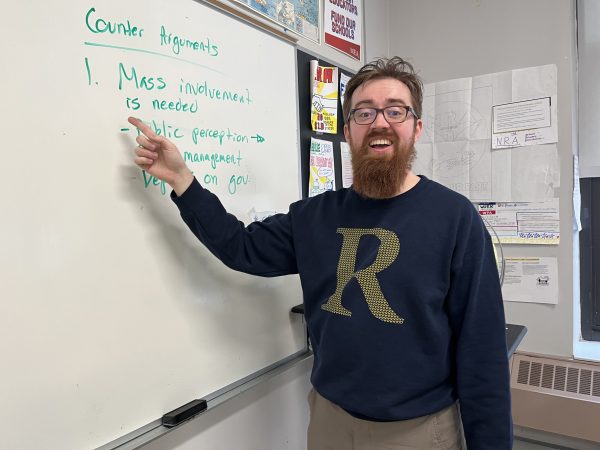

An OB-GYN at the University of Michigan, Dr. John Randolph has been the fellowship director in reproductive endocrinology and infertility at the University since 2003. He helps counsel couples who are struggling to have biological children and has worked closely with the process of artificial insemination for 37 years.

In addition, Randolph is familiar with the process of in vitro fertilization, or IVF. As opposed to artificial insemination, with IVF the initial growth and development of the embryo takes place in a lab.

“The way I see it is that you take gametes out, put them together, and then put them back in someplace where they can grow,” Randolph said.

Leah van der Velde’s story begins with IVF. During van der Velde’s freshman year at Community High, they learned that their conception differed from what they had always assumed.

“I was writing an essay about my ancestry for U.S. history and I asked my older sister if I could look at her old paper to take inspiration. In reference to our Dutch ancestry, her paper said that we weren’t actually related to anyone Dutch because we were born through IVF,” van der Velde said. “No one in my family had ever told me before then.”

Van der Velde was stunned by the news, but had no urge to unearth either of their donor’s identities, particularly their male donor.

“I don’t think I’ve ever needed a father figure,” van der Velde said. “My mom provided for us, and she’s been a great parent. I’ve never wished there was someone else.”

However, a possible half-sibling connection intrigued van der Velde. Their sister took a genetics test while writing her ancestry paper and a handful of matches appeared in her results. Van der Velde believes that these matches could be their biological half-siblings related to them through one of their donors.

“There has been [some conflict] since I’ve become more curious about my siblings,” van der Velde said. “Everyone in my family is very non-confrontational so when I found out, I didn’t talk to my mom about it at all. Over time, I worked it into the conversation, so that she knew that I knew about it.”

The prospect of additional people related to someone through the donor is a moving one. It brings comfort in the knowledge that there may be other people to form close relationships with in the future. And despite their subtle approach, van der Velde is excited about the idea of having half-siblings out in the world.

In addition to inseminations conducted in a lab or through a sperm bank, there’s another method that prospective parents use: home insemination.

“If somebody has a donor they want to use outside of a sperm bank, they can,” Randolph said. “With home inseminations, [the parent] will find a companion or a friend or somebody, and just get a semen sample which they use instead of a sample from a bank.”

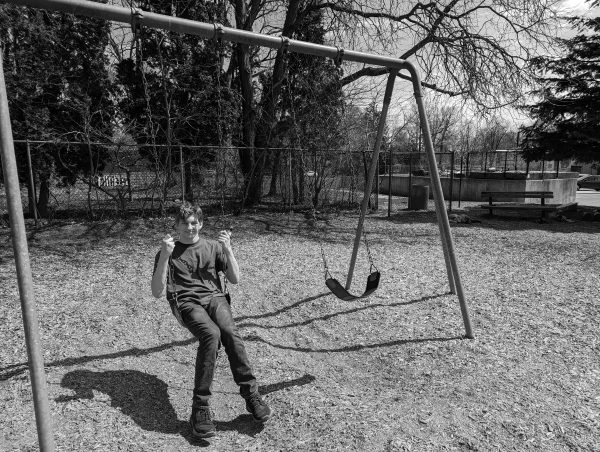

Walden Jones-Perpich’s parents chose to do a home insemination for their two children. By the time he was 10 years old, Jones-Perpich wondered about his donor constantly.

“I used to bug my parents to tell me who he was,” Jones-Perpich said. “It felt like I was playing 20 questions all the time.”

Jones-Perpich’s moms had previously told him that his donor was not from a sperm bank, but was someone their family knew personally. Despite his strong desire to know his donor’s identity, Jones-Perpich wasn’t looking for a missing piece of himself that could be found through discovering his biological father. He was driven by curiosity— the thought that there was knowledge about himself and his biology that his parents possessed, but couldn’t access himself.

Eventually, he didn’t have to keep wondering. After months of asking questions, Jones-Perpich finally received an answer.

“It was very surprising to figure out who my donor was, because he’s somebody that my family and I see semi-regularly,” Jones-Perpich said. “When my parents first told me, I was like, ‘Oh, huh.’ ”

Jones-Perpich’s donor turned out to be a family friend who he visited in South Carolina every spring break with his older sister Loey Jones-Perpich, and their moms. The donor has two kids of his own, who Jones-Perpich had known long before learning his relation to them. Although the donor’s children are his biological half-siblings, Jones-Perpich’s relationships with them feel different than the one he has with his full sister.

“When I think of the definition of a sibling, my relationship with them doesn’t fit into that,” Jones-Perpich said. “They’re not somebody who I’ve grown up with at all, not like Loey.”

Randolph believes that these experiences of kids being born non-traditionally is a beautiful thing and that their stories are important.

“Everything I’ve seen over my career is the evolution in how we define families, and how creative we can be in helping people have families,” Randolph said. “There are so many ways to be together, and to be happy. And [these stories are] just another manifestation of that.”