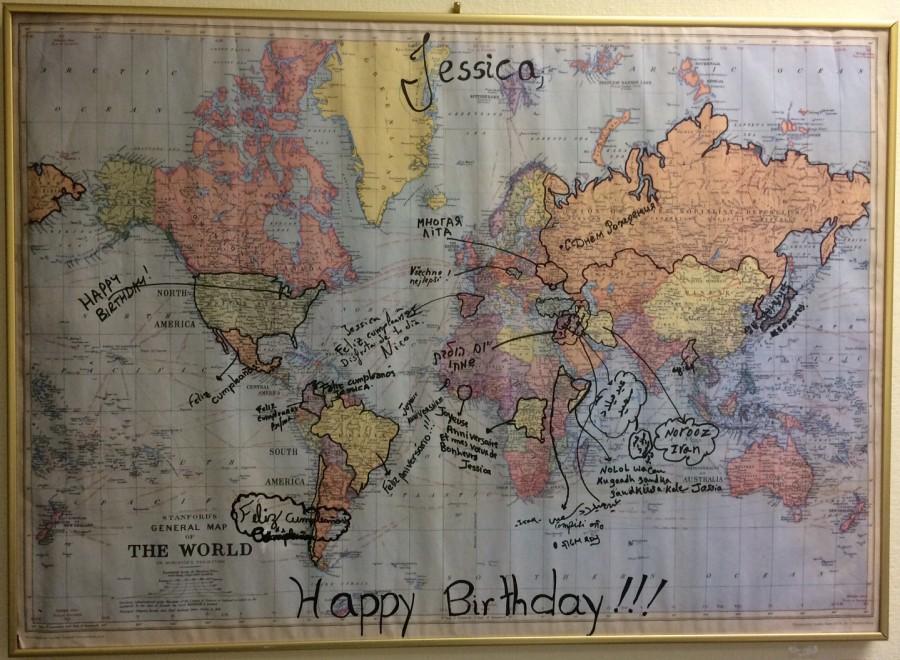

Jessica Vinter has worked with the program for five years and teaches Intermediate and Advanced classes. For her birthday she received this map as a gift from her students. Vinter said, “It’s a birthday card. Isn’t it the greatest birthday card ever? They said ‘happy birthday’ all around the world. So each of those countries is where my students are from. “

With a New Life, a New Language

Getting to America is only half the battle for immigrants. For many, learning English has proved critical for success in America.

February 15, 2016

Husseen Al Ali* heard explosions as he dashed out of his home in Homs, Syria. Carrying his son and a few of his things, he, his wife and his five children ran to get on a bus while people yelled, “Hurry up! Hurry up! Hurry up!”

The bus took them from Homs to Damascus, the capital of Syria. Al Ali had left Homs so quickly that he could not bring much with him. Once in Damascus, he bought some food and clothing for his family. The next step was getting from Damascus to Daraa, the border between Syria and Jordan. Al Ali had arranged for a friend to drive him and his family. From Daraa to Jordan, they continued, but this time they had to walk along the road.

“[It was] about two hours walking. 11 [at] night,” Al Ali said. He and his family continued until they reached Zarqa, Jordan. They stayed there for three years and resumed a somewhat normal life. His children — three daughters and two sons — attended school there. But his sister-in-law, who had already been in Michigan for ten months, awaited them in the United States.

Al Ali and his family finally arrived in Ann Arbor on Sept. 17, 2015. But they still knew adjusting to their new life wouldn’t be easy. They had left everything in Syria.

“I am forgetting my home,” he said.

Starting over

It has been difficult for Al Ali’s family to adapt to the big differences between America and Syria, like being away from his family. Al Ali has two sisters still living in Syria, and he is not used to being so far away from them. The freedom in the U.S. is also striking to Al Ali. In Syria, he had fewer privileges, and now he has the complete opposite.

“Here, [there is] too much freedom. It’s good sometimes, but it’s too much,” he said. “Like when the kid of sixteen years is taking driving lessons … You must take bus! No cars!”

Despite the difficulties of living in a new country, there are many positives to living in America. Most importantly to Al Ali, safety is no longer an issue for him and his family. He imitated the sound of explosions and said that he no longer hears them.

“I am sleeping in my bed. But in Syria, no sleeping. [I am] scared,” he said.

Al Ali has high hopes for living in America. He said that everything is expensive but he is confident he will get a job and money to buy food.

“I wish I have a good job. I wish my children [will] study in America [and have a good education] for their future,” he said. “I hope I speak English as an American.”

A place for immersion

This is why he comes to the English as a Second Language (ESL) Program at Jewish Family Services. Al Ali takes classes with other non-English speakers, some of whom are refugees and others who are on student visas.

The ESL program, which has been serving refugees since 1997, originated as a resettlement for Jewish refugees mainly from Russia. It has begun to turn into a place with refugee services such as immigration aid and ESL. The program is drop-in style: students come as they wish, depending on their work schedules and children. Currently there are about 120 students from 20-25 countries, ranging from Iraq, Syria, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and other Middle Eastern countries, to Nicaragua, Ecuador and other South American countries.

Jessica Vinter began as a teacher for the program and eventually evolved into being the Program Coordinator. She knew she wanted to work for an organization providing public service, and also had previous experience teaching Russian, Spanish, English literature and ESL. Vinter understood the importance of these refugees learning English.

“When they are living in another country for extended periods of time or permanently, it’s not a question of wanting to learn English, it’s an absolute necessity to learn English,” Vinter said.Beginning, Intermediate and Advanced classes are held three days a week, in the mornings and afternoons. Vinter teaches the Intermediate and Advanced classes. She begins her classes with 20 minutes of speaking, where students walk around the room with a script given to them and make conversation with the other students in the class. Vinter also teaches reading, writing, grammar and culture.

During one class taught by another teacher, students looked at a picture and described what was going on by forming sentences using the names of the other students in the class. They put these sentences on the board and read them; afterwards, the teacher corrected their spelling and pronunciation.

Volunteers also come in to help the classes and work individually with students as conversation partners. Al Ali worked with Nancy Szabo, on one recent afternoon this past December. They looked at the same picture that Al Ali was working on in class. This time, he was to form multiple sentences for Szabo.

“Okay so tell me some of the things you see in this picture,” Szabo said. “What is happening?”

“They are dancing on the ice,” Al Ali replied.

“And what are they wearing?”

“Hat.”

“Okay so she is wearing a hat, and he is wearing a hat. You say they are wearing.”

“They are wearing hat.”

“Hats. So more than one you put an s at the end. She is wearing, he is wearing, they are wearing.”

After this, Szabo goes on to explain the drop the “e”, add “-ing” rule to Al Ali, a rule that Americans learn at a very young age.

Seeing her students’ English improve is one of the reasons Vinter loves what she does.

“[The most rewarding part of the job is] seeing people make progress and make huge strides in their life goals, and not knowing English is a huge obstacle to that,” Vinter said.

She recalled the memory of a student from Senegal who came six months ago, knowing almost no English, who is now applying to the University of Michigan and taking the Advanced class at the ESL program. Vinter explained this while pointing to his transcript, which she had on her desk. Another one of her students came from Congo, also knowing no English. Now she is studying nursing at Washtenaw Community College.

JFS does so much more than just teaching English. They expose the refugees to the community by taking them on field trips to places such as the Farmers Market or the Botanical Gardens, going to museums, and having potluck lunches. They support families with employment by helping them apply for jobs. Some refugees can not afford a car, so JFS gives them a bus pass. A food pantry is available in the building as well as clothes on hand. The organization does whatever they can to help the refugees during this difficult time, and also serves as a safe and comfortable place to show the refugees that people support them.

“They come here, there are people that are just like them, in the same situation,” Vinter said. “They know they can come here any time, and learn English and socialize, and get help.”

*name has been changed to protect anonymity