Behind the beautiful American smile: one adoptee’s journey from Russia to Ann Arbor

March 15, 2019

*This article contains details of abuse and violence, which may be triggering to some readers.*

In the family room of his two-story orphanage in the town of Chebarkul, Russia, 12-year-old Oleg Lougheed watched his future adoptive mother scribble down a few of his potential American middle names as they sat together on the couch. It wasn’t until the fifth or sixth name on the list until he recognized one: Michael.

Although Lougheed had never seen a basketball in his life, he was inspired to take up this name because of Michael Jordan: a symbol of identity for him. It provided a sense of familiarity to Lougheed, and it became one of the few American words he knew when he was officially adopted in a courthouse in 2005:

I do accept my name as Oleg Michael Lougheed.

Three years prior, Lougheed gave himself up for adoption at age nine. For the first nine years of his life, Lougheed found himself being tossed between wherever his mother’s boyfriends were staying and where his sister lived, who was 18 years older than him. His father disappeared early in his life – Lougheed had heard rumors of his father being killed or in jail because of killing someone, though none were ever confirmed.

His sister became his legal guardian when his mother stopped pursuing her nursing career and turned to drinking. At around 20 years old, his sister became the parental figure to her toddler-aged brother and was told by their mother that Lougheed was now her responsibility:

This child is for you.

Lougheed had multiple memories of fights between his mother and his sister. After witnessing such events and being juggled around, Lougheed decided he needed to change the trajectory of his life by giving himself up for adoption.

“I wanted to bring my family back together one more time,” Lougheed said. “But I couldn’t.”

In turn, he had to give up his sister’s right to be his guardian, whom he speculates had immense guilt giving him up. He remembers his sister standing behind him as they approached city hall. There, the woman in charge of placements in the orphanage described the vast benefits of their orphanage:

His own toys, food, shelter and everything Lougheed wanted to hear was detailed in this woman’s description. While Lougheed felt saddened by giving up his parents’ rights, he felt that the orphanage had the tools he needed to escape his current reality. So he agreed to waive his sister’s rights and turned around to face her yet again.

She was covered in tears.

The day he was introduced into the orphanage, he and his sister held a bag of his clothes. Walking through front doors, they were greeted by a caregiver and eventually the director of the orphanage. The two of them were given a brief summary of what the orphanage was like and when his sister was allowed to visit. He gave his sister a final hug, as she wasn’t allowed to go upstairs to where he was staying.

Once upstairs with the caregiver, he was paired up with an older orphan, who subsequently gave him a tour of the orphanage, which was split up into 3 “families.” “Family one” operated in the left wing of the second-floor; “family two” lived in the right wing of the second-floor; lastly, “family three” was responsible for the area by the doors over from the office of the director.

There was an emphasis on independence for the orphans because once they aged out of the orphanage, they were immediately thrown into society with no aid. Cleaning their assigned rooms, serving meals to their fellow orphans and hand-washing dishes were done daily to put emphasis on chores. They would rotate rooms to clean and jobs to fulfill, weekly, on top of their schoolwork.

In the weeks that followed, it was made clear that the threat of physical and verbal abuse was a common discipline for the orphans.

Depending on the caregiver, any time an orphan had poor schoolwork, forgot to do a chore or failed to do their job, a child would be made an example to the “family.” The caregiver would sometimes order older orphans to beat “trouble-makers” as they were standing in the middle of the room.

The older orphan ended his tour with choice advice for Lougheed.

If you say anything, you’ll be punished.

Lougheed ended up running away in his first week there, jumping the fence of the orphanage and running to see his mother. He explained to her the abusive conditions of the orphanage and begged her to take him back. He remembers her saying something along the lines of “I’ll try.”

Despite his mother’s words, he knew that this orphanage was most likely his living situation indefinitely. When he returned to the orphanage, he was beaten in front of the other orphans for the first time.

His mother ended up visiting the orphanage just twice in the three years he was there: once sober, giving him a bag with orange juice and chocolate, and once so drunk that the workers would not let her in as she pounded on the doors to the building.

Even when his sister would visit him, whether it be once a week or once a month, he was fearful of the workers and caregivers overhearing him exposing the true conditions of the orphanage. The sole visitation spot was located directly across the director’s office as well as the break room where most workers hung out. In fear of punishment, Lougheed had to tell his sister that everything was fine. While the orphanage provided food, water and shelter, it was a stark difference from the place described to him by the administrator.

“It was a tough pill to swallow to know you picked something that you had to live with,” Lougheed said.

It would be three years until Lougheed and eleven other Russian orphans would head to America for a “tryout” period for adoption. Performing folk singing, a music requirement that Lougheed took interest in at the orphanage, they flew to Ann Arbor in exchange with the Hands Across the Water adoption agency in Michigan. Lougheed first met his adoptive family at a performance in an Ann Arbor church.

While folk singing was a chance for Lougheed to express a lot of feelings and trauma, pleasing the audience was still an integral part of it. There was so much emphasis and preparation on every single performance, and Lougheed speculates that the orphanage received more funding and recognition if they placed well in competitions. He felt that in order to not be punished, he had to excel.

When he returned back to Russia from America, part of him was insecure about his performance. He wasn’t sure if his folk singing translated into art for the American audience. The other part of him was reassured by his adoptive parents, who had kept contact with him since he left America.

The orphanage dynamic immediately changed when workers at the orphanage found out he would get adopted. He was put on a pedestal. Abuse decreased. And positive remarks were constantly given out:

Look at that beautiful American smile.

However, there was a snag in paperwork, which caused a delay in the court date for Lougheed to get adopted. Uncertainty built up in him and things at the orphanage appeared to go back to normal. Positive remarks began to subside; if Lougheed forgot to do chores or got in a fight with the family, then he was in trouble like before.

Luckily, his adoptive family still had the intention of adopting him, and the entire family flew to Russia on the new court date.

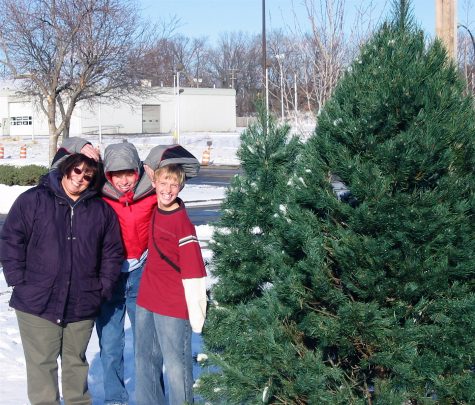

Standing on the steps of the orphanage, preparing to leave Russia, he found himself seeing his adoptive family, consisting of a mother, father and brother on the left; his sister, his cousin and one of his sister’s friends were on the right. He was saying goodbye to not only his past three years of life in the orphanage but the birth family that he had known for the first nine years of his life.

Once he reached America, he found new struggles when it came to interfacing with others. Enrolled at Ann Arbor Open middle school, he felt embarrassed as he was placed amongst five year olds to learn English and catch up in his education. His first two years of communication with his parents consisted of pointing at words in a paper dictionary. And when those words failed to express his frustration or anger, he found himself spilling his emotions onto his parents, who could not fully understand his broken English and the difficult experiences he was going through: not only as an adoptee, but as an adolescent.

Calling his sister and his aunt in the first year in America resulted in expensive phone bills. Once, as he hung out with his friend from Ann Arbor Open, he nonchalantly called his aunt for about an hour before hanging up. His father later came up to his room and suggested that they find a new form of communication, like Skype or Facetime. Lougheed misunderstood this as the phone bills being too high, so he could not call his relatives in Russia again.

He would not call again for seven years.

It was not until he began being a pupil of Rick Hall, his sixth-grade teacher at Ann Arbor Open, where he truly began feeling seen by others than his family. Hall was one of the first people to stay with Lougheed before, during and after class to teach him math, science, English and computer skills — always staying the extra hour.

Catching up was difficult, but eventually Lougheed found himself proficient in English. He found an interest in reconnecting with his past through the Community Resource program at Community High School, which allowed him to begin taking Russian classes at the University of Michigan. He stopped having to use the paper dictionary to talk to his parents. He made friends.

Around the high school, he began seeing fellow adoptees, who were adopted around the same age he was adopted, with some of them having a lot of difficulties because of such factors as the language barrier. He found himself asking why he was able to overcome the abuse and neglect he faced in Russia, and the language barrier and uncertainty he faced in Ann Arbor.

“Why was I put through the same exact test but able to overcome some aspects of that?” Lougheed asked himself.

After graduating from Kent State University with a degree in Russian translation and a business minor, Lougheed found himself in Newark, Delaware at an accelerated business program, along with a mentor that encouraged him to explore his interests. Lougheed then came to the conclusion that his own purpose in life was to share his story.

He sat down and wrote his story in chronological order, finishing it with an imperative for readers to share their own stories. He titled the blog post “Overcoming Odds.” Over the next couple of days, he began getting email inquiries, stories of other adoptees and began asking himself yet again, “why me?”

He realized that the people wanted to be heard, validate their experience and look for a sense of community. A two-page blog post became a platform for them to share experiences, as well as a place for foster parents or adoptive parents to understand the different perspectives of foster and adopted youth. Yet people submitting a story wasn’t enough to connect with their past. He felt there had to be something else in addition for stories to be told and voices to be heard.

Lougheed took inspiration from his blog post and started his own podcast and organization called “Overcoming Odds” in 2017: its main theme revolving around telling the stories of foster and adopted youth.

Lougheed has created opportunities for these groups to tell their stories by holding conferences throughout the country with speakers on foster care and adoption, talking about different aspects of a current theme. Their first conference, called “Hear Me Now,” was held in Austin, Tex., and hoped to share the formerly unheard stories of foster youth and adoptees, as well as provide universal tools for success.

Coming back to Ann Arbor for a conference was important to Lougheed, and establishing the theme of the event in Ann Arbor as “Seeing is Believing” was essentially paying it back to the family that welcomed him, the educators that spent their extra hours teaching him and the peers that supported him throughout his journey; these were the people that saw him at his weakest moments.

Planning the event in Ann Arbor has not been easy: sometimes he feels that organizations need an extra push to understand the importance of telling their stories. The conference will be held on March 16, from 12-5 p.m., featuring guest speakers on foster care and adoption, including Lougheed himself, who is giving a talk appropriately titled “Everyone has a story. Live yours.”

“We all have a story to tell,” Lougheed said. “We have a responsibility to live that story. Live the story that suits yourself. The end goal is to show journey of a single story, and [to show] how we can change people’s lives if they decide to listen.”

***************************************

During his sophomore year in college, Lougheed was able to find his birth sister’s friend through an adoptee-recommended messaging app called Classmates. Sending her a message, his sister’s friend then sent him his sister’s profile.

In a three hour Skype call, Lougheed saw his sister for the first time in ten years. She cried for the majority of the call, saying that all she wanted was to see his face again. She had thought that he intentionally never called back ten years ago. In the call, she reminded him of a memory that he had long forgotten about, particularly, the last words he said to her before departing Russia:

I am going to become a Russian translator and save you.

Although these particular words had exited his memory long before he arrived in America, he felt that, subconsciously, he had fulfilled this goal, more than ten years after his adoption.