As I watched my family walk toward the edge of a cliff, I panicked. I scooted along on my multicolored skis with my brother at almost 13,000 feet above sea level and felt the snow under me, as thin as my confidence. I thought about what would happen if I fell. My fear took control: I wasn’t doing this run. Despite the 10 years of skiing under my belt and my brother’s whining of wanting to do the run, I couldn’t.

I hate being scared. But more than anything, I hate my response to being scared. Fear is healthy when it is protecting us from something dangerous, when it’s a survival instinct. In the case of the run, though, everyone who did it was fine, and I ended up missing out.

I don’t need to jump off cliffs to be fearless, but I do want to be brave and know that I can fight the power of fear. But that’s really hard.

I feel like every day I come home to my dad fighting a battle with fear, telling me about another value being targeted by the American government. He tells me about the takeover President Donald Trump is planning in the Middle East and the ongoing deportation of thousands of immigrants. It feels like just another reason on the stack of ones to fear the power of this man: it’s taller than the towers that display his name across them.

But what may be even more unnerving is that fear is what got Trump to this position of power and feeds his influence on the American people on all sides of a divided country. Through his exploitative yet common use of a natural human instinct, he has become the protector of the evils that he has intensified.

Donald Trump, in addition to his 34 felony counts, is guilty of a psychological crime. He is using fear to short-circuit the minds of Americans left, right and center.

Only a few months ago, Americans couldn’t get through even a YouTube video without hearing claims of unconstitutional behavior of political candidates set to dramatic music. In many cases, these accusations specifically targeted the fears of viewers. Every time I turned on the TV, I was welcomed by an aggressive male voice telling me that Ellissa Slotkin would hurt Michigan’s economy or that Mike Rogers wouldn’t protect my reproductive rights. These commercials, like so many others, were an attack, an army sent to the brain, meant to deactivate critical thinking.

That’s what fear does.

If I am told that funding is being taken away from schools, my first thought isn’t about what kind of fundraising can be done; it’s just worst-case scenario thinking.

I would think that I wouldn’t have the resources I need, scared for the teachers I love. This is helpful when fear is acting as a survival instinct so that one isn’t thinking too critically if being chased by a predator, but it is dangerous when used as a weapon against one’s own kind.

When Trump reinforces negativity and terrible consequences on issues like immigration to rally-goers, their minds go to this place that exists without critical thinking. He capitalizes on this vulnerability by presenting himself as the savior.

On the night of Oct. 28, 2024, I spoke with a scared man from Dearborn, Michigan, at a Kamala Harris rally. I knew TikTok had fed him information that could shroud him in a dark, untrusting, fearful view of the world. What I did not know was just how much power that fear had over him.

Instead of answering the questions I asked, he redirected back to what he wanted to talk about. He moved his hands in and out when he talked about abortions and immigration, reminding me of the man who had inspired much of what he felt.

Donald Trump holds power over almost everyone, not just those who trust him.

In the case of American people who oppose Trump, values being jeopardized can push and push until they are trapped in a space not too different from that of his supporters. Sometimes, I find my loved ones in this space.

Sometimes, I find myself in this space — and often, it comes from a combination of fear and frustration. It’s a space of worst-case scenarios.

Trump has a position to hold as much psychological power over the people of the U.S. as legal power, but this psychological power doesn’t mean anything. That is, until it motivates action, and it so often does.

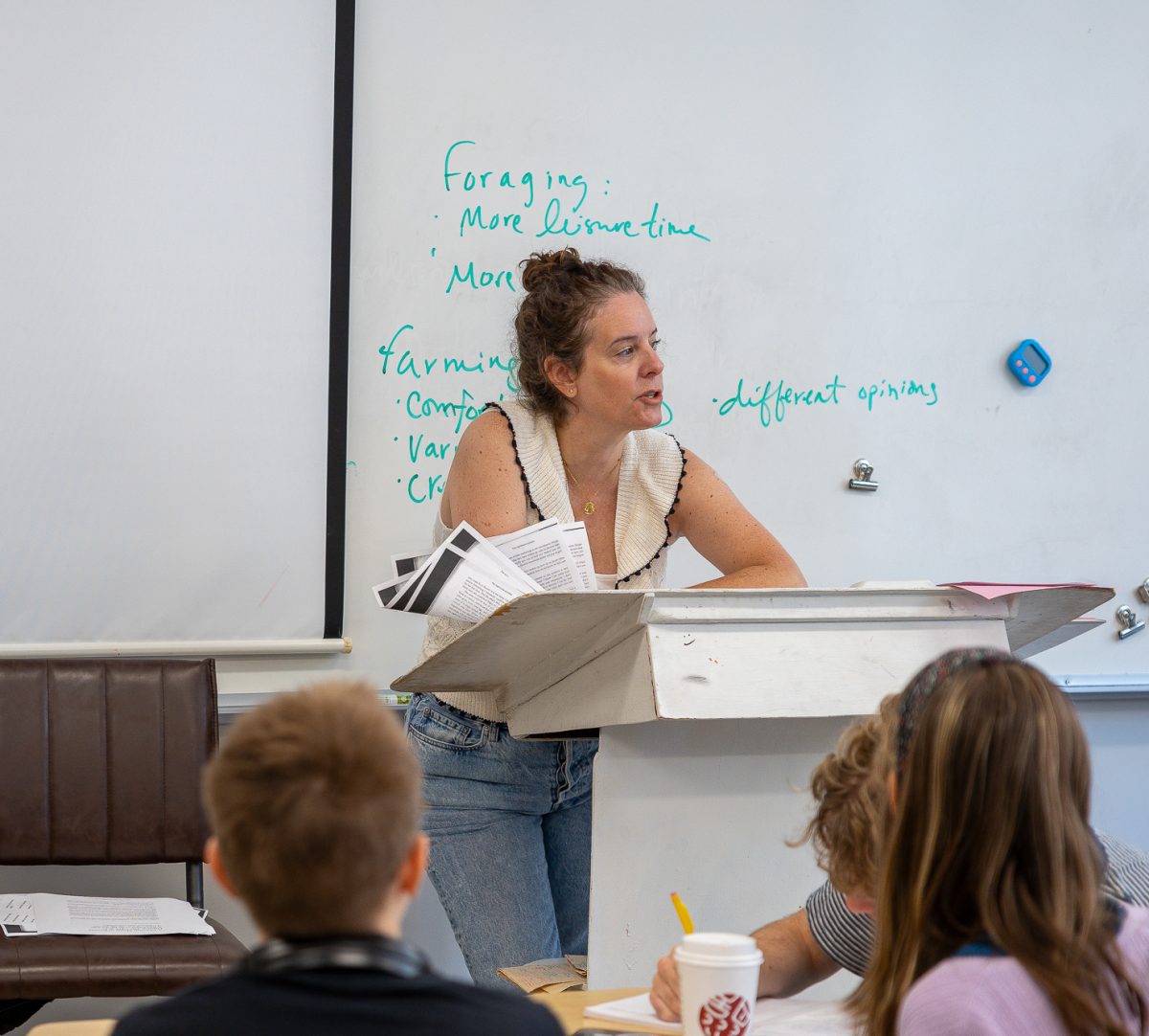

CHS history teacher Chloe Root sees one of the most dangerous effects of fear in her students and in her loved ones: self-policing.

Root teaches her U.S. History class through the lens of race, class and gender, an offense that could get her fired if she lived just 60 miles south. Ohio is one of the many states that have put restrictions on teaching diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). Concerned and scared students have asked Root if she will continue to teach classes that deal with DEI, but Root knows her rights. For now, Michigan is a place where Root can teach these topics, and she will not let fear control her. She will not give up the rights she has.

“If we start to give up our rights preemptively, then we’ve already lost,” Root said. “I think the really scary thing about fear is that it makes people obey the directives of someone who doesn’t actually have authority to do what they’re doing.”

This self-policing that Root sees is a result of the emotional response that fear initiates — that bypass of critical thinking or a lack of a full assessment of the situation. Recently, Root’s partner expressed his own fears about her safety due to the bumper stickers on her car.

“I’m not going to live in a world where I can’t have my bumper stickers,” Root said. “I’m not going to then change the way I do the things that are important to me.”

The bumper stickers aren’t just stickers. What’s important to Root is that she can express her opinions and stand by her values. Some of the words on the back of her car may be at odds with the Trump administration, but Root has the right to stand up for what she believes in, and that is powerful. Root gets scared, too; but she has to remember not to let this fear take over.

“People are afraid of being targets, they start to be like, ‘Oh, wait, maybe I need to be more careful, too,’” Root said. “I’ve had those thoughts, but then I’m like, ‘Whoa. You need to stop yourself, you need to keep doing the things that you do that matter because otherwise, you’re just letting them win.’”

Root sets an example for resistance: she isn’t going to stop doing the things that are important to her. Even the little things, like the bumper stickers on her Honda Fit.

I am unified with many others on the stance that it sucks to live in a world where you can’t rely on the validity of the news you hear, but that just means we as Americans have to question what we hear and see. We have to use our critical thinking. In the U.S., people have the right to speak out, and as long as that’s true, Root will be taking advantage of her rights. So will I, and I hope that the rest of our country can, too, by questioning that fear, taking that power and jumping off that cliff.