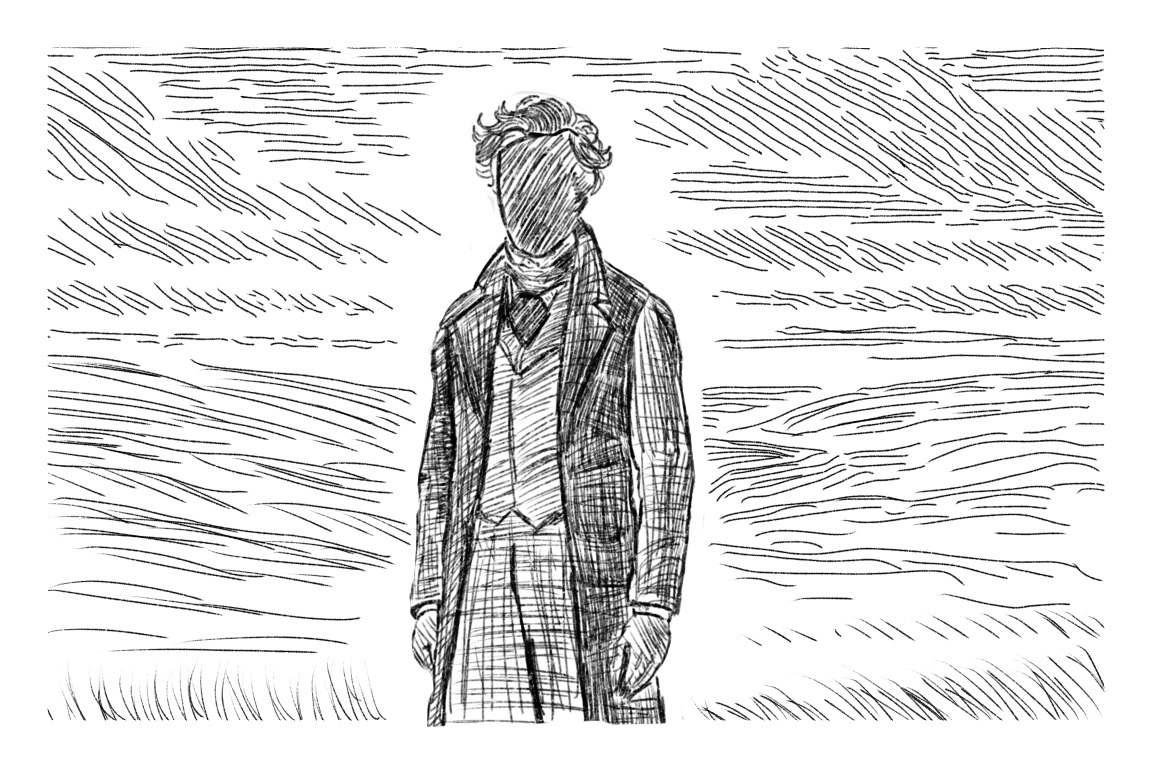

Somewhere between the battered cliffs of Yorkshire and the production rooms of Hollywood, Heathcliff has lost his face again.

Heathcliff, the brooding centerpiece of Wuthering Heights is a character defined by as much mystery as by menace. Equal parts lover and tormentor, he remains one of literature’s most haunting antiheroes

When it was announced that Jacob Elordi and Margot Robbie would star in Emerald Fennell’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights, the announcement sparked the kind of swift, collective outcry that only the internet can deliver. But this is not just another instance of fan nitpicking, like when Daniel Craig was cast as James Bond in the 2000s. Something deeper and repetitive for all adaptations of Brontë’s work was at stake.

At the center of controversy is Heathcliff, one of English literature’s most brutal, inscrutable and romantic antiheroes. Bronte, with her ambiguity, describes him as a “dark skinned gypsy,” a “little Lascar,” an outsider who is radicalized, brutalized and made monstrous by the world that refuses to see him in his entirety. Heathcliff is not a blank canvas but a figure carved from marginalization, coded with a kind of ethnic ambiguity that Victorian readers would have found unsettling, and deliberately so.

Heathcliff’s racial ambiguity is central to the plot’s emotional and social machinery. He is repeatedly dehumanized by other characters, not just because he is poor and orphaned, but because he is visibly other. The Earnshaws adopt him but never quite accept him; Hindley abuses him and Cathy ultimately chooses social safety over her love for someone the world refuses to see as fully human. Heathcliff’s rage, his vengeance, his slow transformation into the cruelty he once suffered are racialized. His outsider status shapes not only how others treat him, but how he sees himself. To erase or soften that racial coding is to strip its darkest and most essential truths: that the monster Heathcliff becomes is born of a society that saw him as less than man.

And it’s worth noting: Heathcliff’s foreignness would have been even more jarring in Brontë’s time than ours. The British Empire was busy expanding across the globe, and the people it conquered were seen as both exotic and threatening. Heathcliff’s presence in a Yorkshire household wasn’t just unconventional; it was radical.

So when a tall, white Australian is cast in this role, it isn’t just a creative choice. It’s a political one.

The decision to cast Margot Robbie as Cathy adds another, far less problematic layer. Robbie is a spectacular performer, no doubt—but she is also, by all measures, Hollywood’s archetype of female desirability; she’s Barbie. Her casting alongside Elordi doesn’t challenge or complicate the dynamics of Wuthering Heights; it reinforces them, flattening its strangeness into something digestible. The story of ferality becomes a high-gloss drama about two beautiful people in turmoil. Of course, this is show business, which hasn’t cast a brunette Cathy since Kaya Scodelario did something right, finally. The aesthetics win. Politics lose.

It only makes sense that Fennell, Elordi and Margot would continue their partnership for Wuthering Heights. Their collaboration has been a winner from the start. Fennell’s vision for Promising Young Woman and Saltburn, featuring Elordi as a main character, was supported by Robbie’s production team, LuckyChap Entertainment. So when it came to adapting Wuthering Heights, who wouldn’t love playing the complex and iconic role of both Cathy and Heathcliff?

Because at the end of the day, casting isn’t about looks or skill, it’s about ideology. Who gets to be seen as desirable? As tragic? As complicated? As human? These decisions tell us who stories are for and who they exclude. When Heathcliff is cast as a conventionally attractive white actor, it sends a message: even our most feral, anguished characters can only be palatable if they are draped in whiteness.

Gothic literature was never meant to be pretty. It was feral, feverish and filled with decay, taboo and a sense of madness. But in the age of prestige, where polished aesthetics often replace uncomfortable truths, and beautiful gowns, we keep trying to give it good lighting and clean hair. Wuthering Heights isn’t supposed to be aspirational. It’s supposed to be a wound.

Adaptation is interpretation. It’s an act of translation and transformation across time, culture and medium. But this is never neutral; every decision of who plays who, what is emphasized and what is erased is a statement about what we think matters. And in this case, the statement seems to be clear: messiness must be cleaned up, softened and made handsome.

In a moment when conversations around representation are more visible than ever, it feels like this adaptation has missed the very point, not just of the book but of what it means to adapt a classic in 2025. The stories we retell are choices and the faces we cast are declarations. Heathcliff was never meant to be easy or even likable. He was meant to unsettle and remind us what happens to people when they are cast out of the frame.

And yet, once again, he has been cast out.