Before she ever wore the uniform, Kaylee Gadepalli already felt like a scout.

Ever since she was a child, Gadepalli had been tagging along to her older brother’s Boy Scout meetings and events, learning all about the rituals, values and community that surrounded the organization. But as the Boy Scouts of America were only open to boys, she had no opportunity to join herself.

This was all until 2019, when they officially rebranded as Scouts BSA, and allowed entries for everyone, regardless of gender.

“I joined immediately when I was old enough,” Gadepalli said. “I’d always gone to the events and now it's official.”

But for Gadepalli, joining was only the beginning. As a young woman of color entering a space built by and for boys for more than a century, Gadepalli quickly discovered that belonging wasn’t the same as being seen. Still, she embraced the challenge, not just to fit in, but to lead on her own terms.

In scouting, in order to become an Eagle Scout, all scouts must go create a large, well-planned project that benefits a religious institution, a school, or the community and demonstrates the Scout's ability to lead and direct others.

And when it came time for Gadepalli to pursue her Eagle Scout rank, the highest achievement in scouting, Gadepalli wanted her project to be more than something to check off the box. Her brother had created a rain garden at a local elementary school during his junior year of high school, a project she’d helped with, but she knew she wanted something more personal.

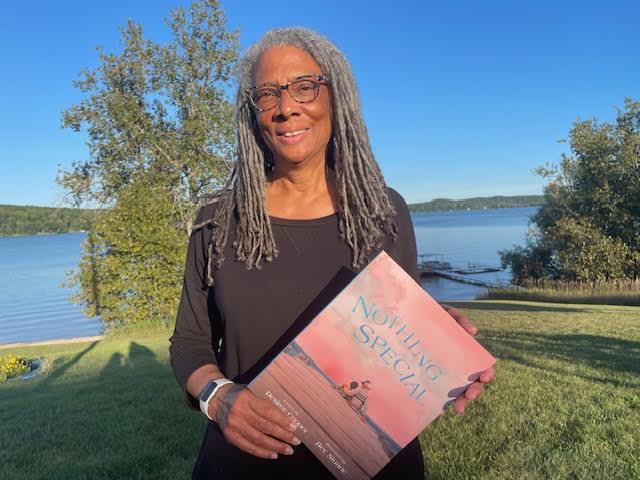

“My dad works at the hospital, so he always tells me all these stories about his patients and how there's a need for books,” Gadepali said. “Reading was super important to me growing up, so I decided that if these people need more books, I want to provide that.”

Specifically, Gadepalli wanted to make sure that kids in difficult situations had access to stories in the languages they speak at home. Inspired by her love of reading and her father’s work at Michigan Medicine, Gadepalli decided to partner with the hospital’s Giving Library, a program that provides free books to children receiving care. When visiting, she noticed that there was a clear lack of books in languages other than English, and Gadepalli saw that as an opportunity.

Planning for the project started in the summer, and a little more prep work was done in the fall. And after a busy winter quarter with little to no work done, mostly due to being busy with extracurricular activities such as Mock Trial and CET, Gadepalli decided to move on to the final step of the project late January.

“I had to finish the project. I was so close and I'd been working on it the whole time, but I needed to lock in,” Gadepalli said. “I needed to actually schedule work days and get stuff done.”

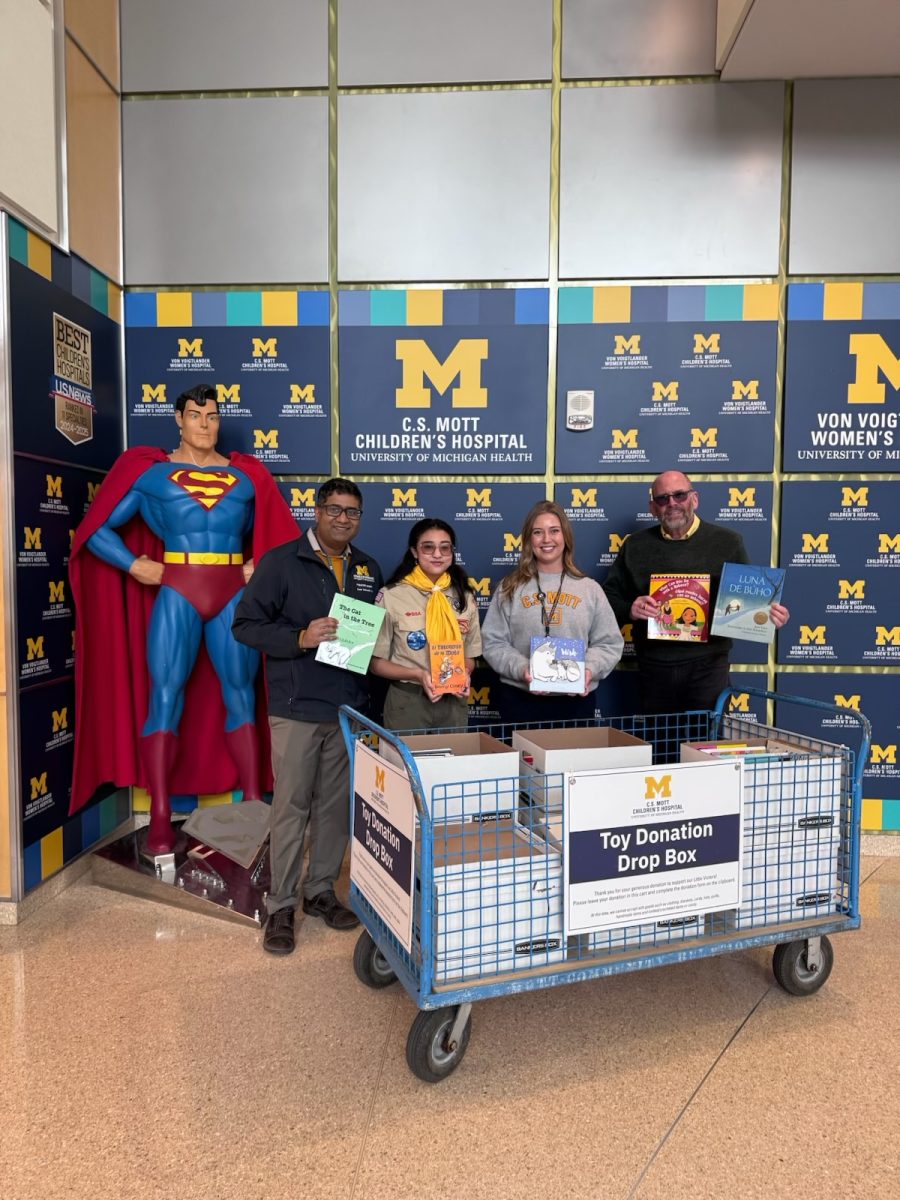

So after organizing volunteers, curating a donation wishlist and much more, Gadepalli went all in on the fundraising over mid-winter break, raising a few hundred dollars in just the first few days. Gadepalli also created a detailed Amazon wish list of titles in Spanish, Arabic, Mandarin, and more, making it easy for donors to contribute. By the end, she had raised enough money to buy hundreds of books for the Giving Library.

Throughout this entire process, Gadepalli found one thing most difficult: tradition.

“The point of it is to be a leadership project, but I don't think leading has to be only you telling people what to do,” Gadepalli said. “I think a big aspect of it is noticing the need in the community, addressing that and doing your best to make that happen.”

In the century-old tradition of scouting, where merit badges and campfire tales have remained relatively unchanged for generations, Gadepalli found herself navigating an unexpectedly difficult terrain. Her project proposal didn’t match with the organization's traditions, creating an unexpected obstacle that went beyond all the paperwork and planning.

“Honestly, the hard part of it wasn't the project, it was just all of the red tape,” Gadepalli said.

In the end, Gadepalli raised over 200 books for the Giving Library, but beyond the numbers, she found deeper connections formed through the process. Her conversations with neighbors during fundraising and interactions with fellow Eagle Scouts who supported her project revealed the continuing cycle of community support.

"I was talking to one of the lawyer coaches in Mock Trial about it," she shares. "He told me he was an Eagle Scout, and he showed me pictures and his old stuff,” Gadepalli said. “He was kind of paying it forward, in a way. And I'm like, maybe one day I'll be an Eagle Scout, and some kid will be like, 'Hey, do you want to donate to my project?' And then I get to pull out my pictures and sort of be part of that shared experience."

For Gadepalli, becoming an Eagle Scout represents more than personal achievement, and also about legacy, paving the way for her younger sisters as well as other girls in her troop.

"It means sort of like graduating and moving up," Gadepalli said. "Realizing my time in high school is coming to an end, my time in scouts is coming to an end, but this isn't over, it's just the next step."

The significance of her accomplishment isn't lost on her. In a world where Eagle Scouts have included presidents and influential leaders throughout history, Gadepalli understands the weight of being able to say she's an Eagle Scout. And who knows? Maybe one day she’ll become the first female person of color to become president, just like how she was in her troop.