In a moment when American pride often feels like little more than a spectacle, one reduced to slogan-draped flag displays and political theater, it feels easier than ever to be disillusioned with the very notion of national pride. The flag has been co-opted, the national anthem has become more a symbol of division than unity and it’s hard to shake the feeling that the America we are told to love has strayed far from its most idealistic roots. It is into this landscape that Beyoncé’s "Cowboy Carter" arrives, a bold, expansive piece on reimagining the very ideal of Americanism. With “Cowboy Carter,” Beyoncé doesn’t just offer up an album; she offers a powerful redefinition of what it means to embrace, interrogate and even love a fractured American identity.

Released in March 2024, “Cowboy Carter” was met with a mix of praise and outright indignation. Some were quick to question if it was truly a country album, but that question felt willfully obtuse. It overlooked the album’s deliberate engagement with country music’s roots and its challenge to the genre’s historically narrow definitions. Beyoncé’s work doesn’t merely adopt country aesthetics; it interrogates and reclaims them, spotlighting the Black origins of country music and confronting the racial gatekeeping that has long excluded artists of color. By collaborating with country legends like Dolly Parton and Willie Nelson, and featuring voices like Linda Martrell, she underscores the genre’s diverse heritage. The discomfort wasn’t musical but rather cultural. Beyoncé doesn’t step into the costume of America, she reclaims it.

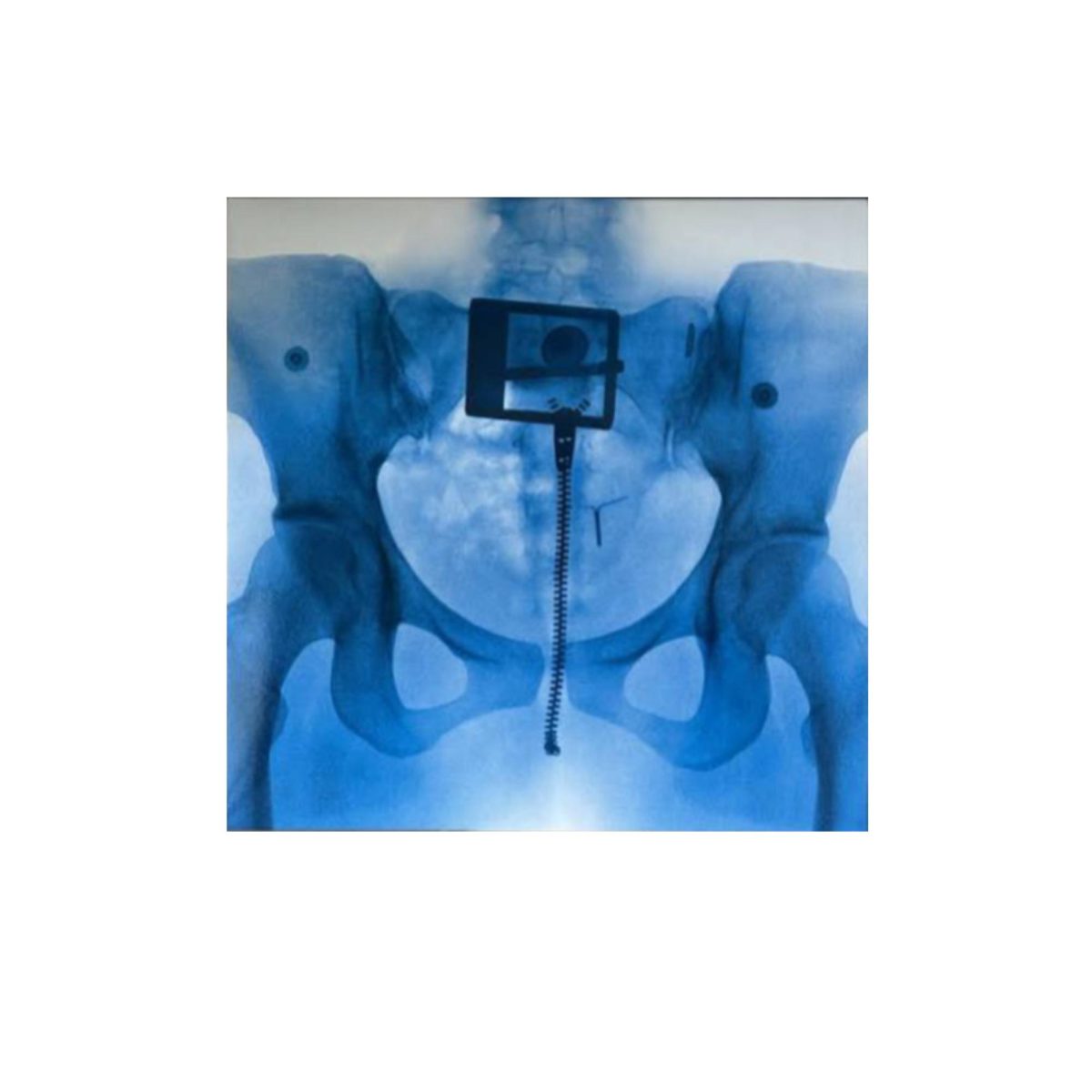

The album travels through southern genres and brings them to the forefront of radio, country, gospel, zydeco and flamenco, which brings the genre argument to a halt. The image of her poised sidesaddle in a red, white and blue leather ensemble, holding an American flag, comes off as a declaration rather than a presentation. She's not asking to be let into the culture; she's already inside, rearranging the furniture.

In contrast, mainstream country music often gravitates towards formulaic expressions, frequently relying on cliched motifs of patriotism and rural life. Morgan Wallen, for instance, while commercially successful, his music’s repetitive themes and lack of stylistic evolution. His recent song, “I’m The Problem,” for instance, is a track that’s emotionally flat despite aiming for vulnerability. It leans hard on the tired tropes that plague country: whiskey as a metaphor, toxic relationships dressed as passion and a vague self-blame that lands as more deflection than depth. It recycles the same imagery that’s come to define the genre's commercial side, offering little new insight to artistry. It’s a reminder that while artists like Wallen play it safe, “Cowboy Carter” was always aiming higher, even if its boldness wasn’t immediately understood.

Still, the rollout gave me pause. The lead single, “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” struck me as my biggest fear: a flat, pop flavored commercial ploy rather than a genuine artistic gesture. It didn’t showcase the depth Beyoncé is capable of, and, more frustratingly, it didn’t seem to care. Had this been the only tone-setter for the album, I would have avoided it entirely. But then came “16 CARRIAGES,” a full bodied, sonically unique song with lyrical and instrumental heft. This was the Beyoncé I was waiting for: audacious, emotive and expansive. The kind of artist who reconfigures a tradition into her tone. And for a brief moment, I was almost grateful for her muse, until I remembered it was, regrettably, Jay-Z.

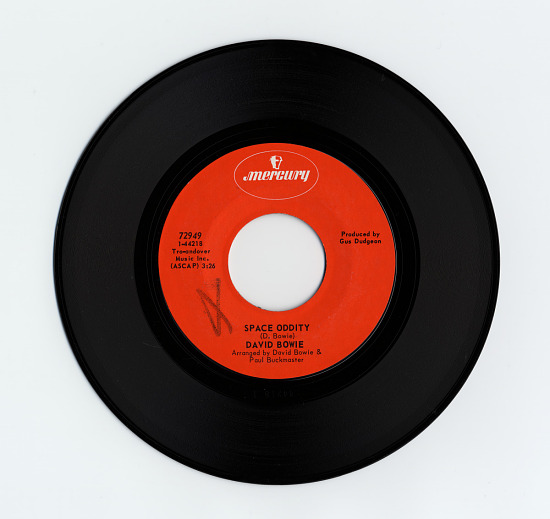

Sonically, the album is sprawling and at times unruly, but purposely so. Her covers of “JOLENE” and “BLACKBIIRD” are among the most radical acts on the record. She sings “JOLENE” not as a pleading woman, but as a warning one, turning Parton’s vulnerability into authority. Of course, with every Beyoncé album, we’re reminded somewhat tragically that the man inspiring such lyrical grandeur, protection and devotion is Jay-Z. Her “BLACKBIIRD” is sparse and reverent, another reclamation. Paul McCartney originally wrote ‘Blackbird” inspired by the courage of the Little Rock Nine—nine Black students who bravely integrated a previously all-white high school in 1957. According to a GQ interview from 2019, McCartney said, “In England, a bird is a girl, so I was thinking of a Black girl going through this—you know, now's your time to arise, set yourself free, and take these broken wings.” Hearing Beyoncé sing it, the lineage becomes literal, a powerful reminder of resilience and hope.

As someone who was born around the time “I Am… Sasha Fierce” was released, Beyoncé has been a continuous presence in my cultural upbringing. I grew up watching her evolve, not just as a performer, but as a creative force who seemed to operate on an entirely different frequency. I don’t share her cultural background or personal history, nor would I pretend to. But what I have always responded to is her precision, ambition and control, she wields performance as both shield and invitation. In a media landscape often dominated by overexposure, Beyoncé’s intentionality has always felt radical. She isn’t just producing music but legacy. Watching her work has shaped my understanding of what it means to be an artist, boundary-pushing and intensely fervent.

And then there’s the joy of it. Songs like “BODYGUARD,” “YA YA,” and “SPAGHETTII” are impossibly fun. They’re catchy, playful and even a little bratty, in the best way. They aren’t burdened by narrative expectations or genre puritanicalism. They are a celebration of the musical freedom America as a country has made. They’re pure joy: the “Partition” and “Formation” moments of “Cowboy Carter,” echoing the liberated spirit of her prior album, “Renaissance.”

But the true triumph of “Cowboy Carter” lies deeper in its tracklist; songs like “II MOST WANTED” with Miley Cyrus, “TYRANT” and most especially, “AMERIICAN REQUIEM” feel like the album’s nucleus. These songs are emotionally stunning, melodically inventive and vocally astonishing as always. “AMERIICAN REQUIEM,” in particular, is a masterwork: a sweeping meditation on identity, myth and a survival that sounds like it was carved out of the American psyche itself. It is a eulogy and a vision in the same breath.

All of this was not unexpected, as Beyoncé at last won Album of the Year at the Grammys after years of being snubbed. That engendered backlash, especially from fans who had expected albums like BRAT and HIT ME HARD AND SOFT to win. Such criticism usually issues from those without a cultural sense of how important Beyoncé has been—and sometimes thinly disguised racial bias. Double standards have been imposed on Beyoncé by her career. For example, artists like Billie Eilish (whose lead songwriter and producer is her brother Finneas) and Elton John (who has collaborated with lyricist Bernie Taupin for decades) have always had co-writers and producers, but are never by any means criticized for it. However, Beyoncé herself is frequently criticized for never writing or co-writing a single song herself. This assumption, rarely questioned of her contemporaries, underscores the disproportionate burdens placed upon Black women in the genre. Critics rarely talk about this imbalance explicitly, but it underlies much of the discomfort with her appearing in places long held for others. Country music—with its whitewashed history and gate kept heritage, is one of them. And yet, here she is, outdressing cowboys, outsinging stars, and doing it all with the finesse of a woman who's seen it all through the industry and dinner with Shawn Carter.

“Cowboy Carter” is not a flawless album. Beyond it’s bad single, certain moments do fall short. But the broader narrative remains: Beyoncé has long been denied her due. Albums like “Lemonade,” which reshaped cultural conversations, lost out to the more traditional choice of Adele’s “25,” even Adele herself used her acceptance speech to acknowledge Beyoncé as a vocalist and musician. More recently, Renaissance was passed over in favor of “Harry’s House,” a decision that felt nearly absurd. So while I remain somewhat perplexed by “Cowboy Carter’s” success in the Grammys, I recognize the symmetry. Perhaps now, fans of Taylor Swift know what it felt like when her self-titled “Beyoncé” lost to “1989.” It’s frustrating, but we move forward.

The “Cowboy Carter” Tour only reinforces this. Visually and vocally, Beyoncé delivers on a level few artists can approach. But that is hardly new— Beychella and the latest Beyoncé Bowl have made that clear. What's different this time is context. She's not working within a genre. She's working above it, below it, around it—reinventing it on the fly. And maybe the biggest shock of all? She's doing all of this without ever once having to need to include her husband. A mercy.

“Cowboy Carter” is not a country album by the industry's standards. It's something else, something more grandiose and more culturally relevant. In a time of political disillusionment and aesthetic exhaustion, Beyoncé has done something I did not expect: she made me feel patriotic. Not the star-spangled, boot-stomping kind. But a new faith that America, even now, is worth fighting for.