Hollywood has never lacked for self-obsession, but rarely has it turned the camera so gleefully against itself as in “The Studio”: Apple TV’s sharp, surreal comedy about the inner machinery of modern filmmaking. As someone far removed from the world of agents, awards shows and greenlights, I’ve never felt much sympathy for the executive class behind the screen, and “The Studio” does nothing to change that. If anything, it reinforces the suspicion that those who run Hollywood are less tragic artists than chic buffoons clinging to relevance, power, and occasionally, a coherent thought. It’s chaos, and that’s the beauty of it.

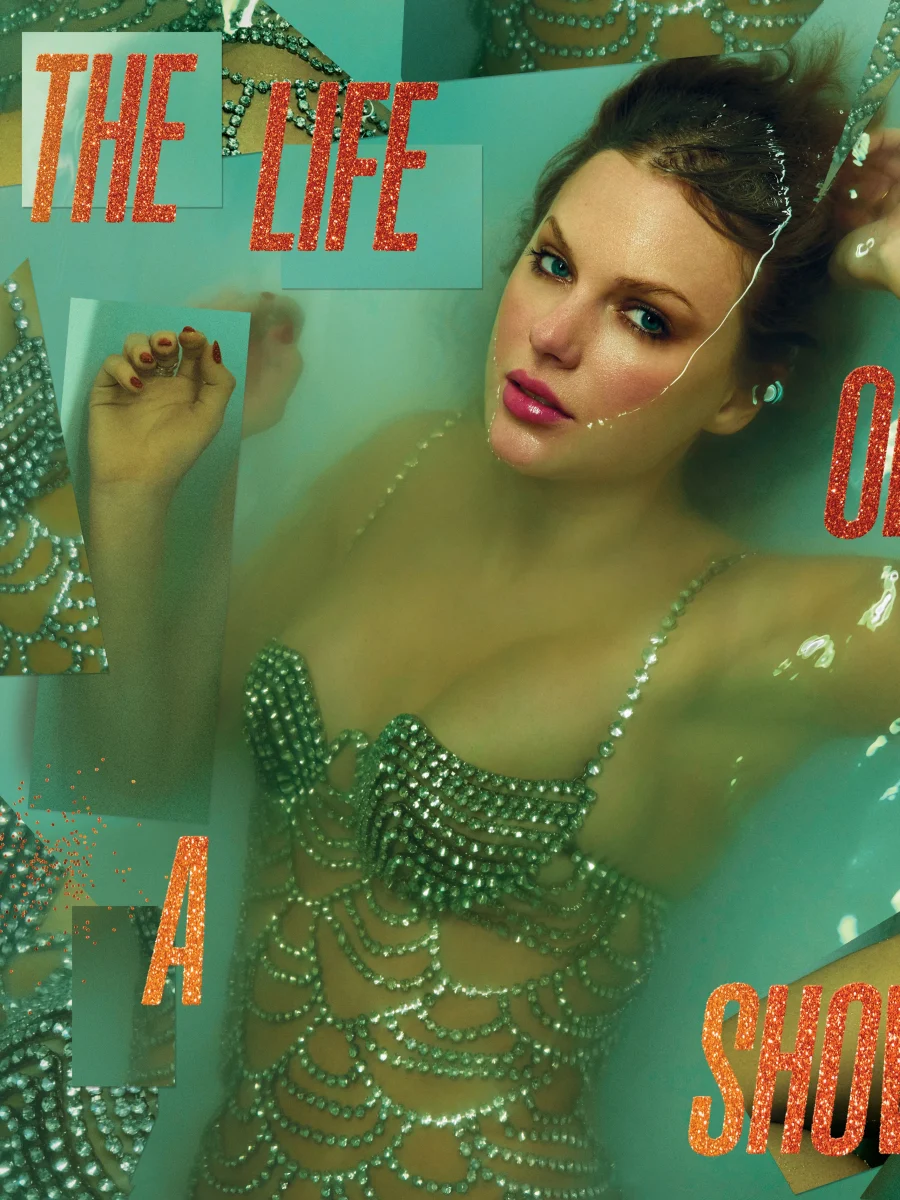

Directed and written by Seth Rogen, who also plays its beleaguered protagonist, “The Studio” opens on a premise that careens between the earnest and the unhinged. Matt Remick (Rogen), a guileless, movie-obsessed everyman, is unexpectedly thrust into leading the struggling Continental Studio. He enters the corridors of power with the zeal of a purist, lamenting franchise excess, streaming-era cynicism, and the general loss of cinema’s artistic ambitions. But idealism rarely survives institutional opposition. Across nine sharp, often hectic episodes, Remick’s moral compass spins utterly out of control, his manifesto abandoned as he capitulates to the very institution he had sought to overthrow

This crumbling of conviction is often played off as comedy, though there is also a pathos to it. Remick awkwardly praises Paul Dano (playing himself) for his direction of “Wildlife”. It’s a moment that is said with so much sincere admiration that it deflates the show’s irony. He’s right, of course — Wildlife is good. And that instant, brief as it is, reveals all about Remick: he’s still a cinephile, even as he’s engulfed by an industry that generally isn’t.

The show’s true ambition is its sprawling, metatextual humor. Cameos aren’t window dressing; they’re part of the show’s satirical machinery. In the first five minutes, Dano appears in a film in the series; later, there is a pitch for a Jonestown biopic by Martin Scorsese; and Ron Howard — known for being the nicest guy in Hollywood — assaults Remick at a boardroom meeting. Johnny Knoxville and Josh Hutcherson appear in a wild horror-comedy. They’re existential jokes, an extension of a larger criticism of Hollywood that no longer knows the difference between reality and performance.

At times, this blurring becomes disorienting in its surrealism. Olivia Wilde, playing a maniac version of herself, directs a clearly exhausted Zac Efron in a parody of crime films, which somehow mutates into a detective story, ending with Wilde tossing a reel down a hill. The entire episode would feel rather ridiculous and uninteresting if not leaning on Wilde and Efron as guest stars.

While Rogen centers the narrative, his character is often overshadowed by the electric performances around him, most notably Ike Barinholtz as Sal Saperstein, an executive so unhinged he makes Remick look sedated, and Catherine O’Hara as ex-studio head Patty Leigh continues to entertain as always. Barinholtz, in particular, is a shock: in episodes like “The Golden Globes” and “The War,” he performs a mania that is outrageous and entertaining.

Visually, “The Studio” is stunning. Certain scenes are filmed in sustained long takes, complicated, detailed sequences that reveal the careful architecture beneath the show’s chaos. Behind-the-scenes footage of the camera motions has been posted online, and it’s equally captivating as the finished product. These stylistic touches aren’t gratuitous; they’re used to sharpen the show’s tension between illusion and effort, between movie magic and the sweat that fuels it.

Still, for all its brilliance, “The Studio” occasionally leans too hard on its star-studded Rolodex. When the punchlines rely solely on the incredulity of a celebrity cameo, they fail. Meta only works when it bites back, and unfortunately, “The Studio” begins to miss at the penultimate episode.

Apple TV, already home to the cerebral oddity of “Severance,” continues its streak of taking big creative swings. “The Studio” is no exception. It does satirize Hollywood, but it also shows the best of it. It is a satire made not from outside the system, but deep within its center.

“The Studio” is a love letter to film, penned with sarcasm and red corrections. It is not tidy. It is not always sensible. But it is, like the industry it depicts, engrossing endlessly.