Desiree Cooper worked for five years in a major law firm in corporate law. Then, one morning, her life changed.

“I woke up one day and said, ‘What’s a nice girl like me doing in a place like this?’” Cooper said.

Cooper left that job and started working for a nonprofit that was “dealing with many of the on-the-ground issues that Detroiters were facing.”

She was in charge of community anti-crime projects and a race relations project.

From there, Cooper went to Wayne State University and studied in their Center for Urban Studies, where she researched anti-crime policies and began teaching classes. Twelve years after receiving her undergraduate degree in journalism and economics at the University of Maryland, she began working as a journalist for the Detroit Metro Times.

“I often say that my resume looks like I have issues, because I went from career to career,” Cooper said.

At the Detroit Metro Times, she went from writing as a columnist to working as an editor to running the paper. She then moved on to working in public radio and working for a free press, acquiring a Pulitzer Prize nomination for journalism along the way.

Amidst all this, Cooper became the communications director for Planned Parenthood of Michigan. Her job at Planned Parenthood was her last full-time job before moving back to Virginia to write full-time and care for her grandchildren.

Cooper believes that each of her previous jobs have impacted her experience with writing.

“I got to know the community. Then, when I transitioned to creative writing and essay writing, there was so much to draw upon, and I had so much more education, empathy and understanding about urban life,” Cooper said. “I knew about the bigger effects of history and race on how people work and interact together.”

Cooper’s story collection, “Know the Mother,” came out in 2016. It’s described by her publisher, Wayne State University Press, as “short, searing glimpses of how race and gender shadow even the most intimate moments of women’s lives.”

“The Choice,” a short film that grew out of her story “First Response,” is a powerful documentary about women’s reproductive rights. It won an award for Outstanding Achievement at the Berlin Flash Film Festival in 2018.

Cooper first considered writing a book for children at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, which she attended in 2019. She stayed in the same house as Marilyn Nelson, an acclaimed poet who writes for both adults and children.

“I was stuck. The project I was working on just wasn’t working,” Cooper said.

That was when Nelson suggested she try writing a children’s book.

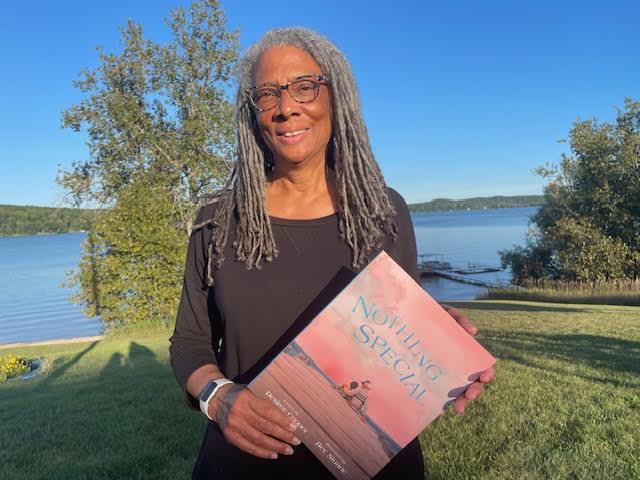

Cooper spent the rest of the conference beginning to write “Nothing Special,” which would go on to be selected as one of the New York Public Library’s 10 Best Children’s Books of 2022.

“Nothing Special” is a story about a boy named Jax and his grandfather. In the story, Jax’s grandfather — his PopPop — talks to Jax about what they’ll do together.

“I think we’ll do some of the things that I did as a boy,” PopPop says.

“Like what?” Jax asks.

PopPop smiles and says, “Nothing special.”

Jax expects to visit the zoo with his grandfather, go to the movies or eat a hamburger. They don’t do any of these things, yet still, at the end of the book, Jax feels like all of his wishes have come true. He went crabbing. He flew a kite that he and his PopPop made. He feasted on crabs and corn, and he sat outside and counted fireflies.

Cooper’s childhood experiences guided the writing of “Nothing Special.”

“It really is based on my life. My dad was born in the 1930s, and he was part of a generation called the Great Migration, where millions of African Americans left the south to go to northern cities, where they sought equal opportunities and a way to climb out of poverty.”

Cooper’s family returned to the south every summer, like so many children of the Great Migration did. Her family would put the kids in the car and drive to Virginia.

That’s the story behind “Nothing Special”: a kid in Detroit travels south to visit his grandfather.

“I think sharing the stories people resonate with helps keep the traditions alive,” Cooper said. “I think that, culturally speaking, the Black experience in America has, ever since Emancipation, been a story of us trying to find each other.”

Cooper’s writing appeared in The New York Times in 2023. Her piece “What if I Hadn’t Been There To Catch Them?” is a beautiful, moving story about her grandchildren and her role as their caretaker.

Cooper’s new anthology, “Black Summers: Growing Up in the Urban Outdoors,” comes out in Feb. 2026. Wayne State University Press describes it as a “triumphant, cross-generational exploration of Black joy and resilience.” Cooper selected work by 28 journalists, poets, essayists and cartoonists from Detroit that addresses how race has impacted their experience with outdoor and public spaces.

At the end of August, Cooper taught a three-day workshop at the Bear River Writers’ Conference, which is held annually in Northern Michigan. Since 2018, she’s taught seven workshops, including ones in flash fiction and editing. This year’s workshop was titled “The Good, The Bad, and the Fascinating: Creating Realistic Characters.”

Cooper says that she was full of faith and determination to become a writer from a very young age. Even when her parents smiled patronizingly at her and asked “Okay, but what are you really going to be?,” even when her college professor called her “illiterate,” and even when her first serious boyfriend took a red pen to her writing, she never doubted that she’d become an author.

However, it was taking on the roles of wife, mother and breadwinner that dealt, as Cooper put it, “a deathblow to my writerly heart.”

“There were too many patriarchal systems railing against me at once,” Cooper said. “I couldn’t hold on to my dreams while fighting on all fronts.”

Cooper gave up her dream, but she couldn’t give up writing. She wrote in secret. She wrote for herself. She “wrote with people who were also holding on to an impossibility.”

In 2015, Cooper’s car was hit by a truck barreling down the Lodge Freeway in Detroit. She could have been killed as she spun across three lanes of oncoming traffic.

Three months later, her first book, “Know The Mother,” was published.

“My younger self had held the faith for my older self,” Cooper said. “My younger self would look at me with a side-eye and say ‘I told you so.’”