Lee Hirsch’s new documentary Bully is a fascinating, horrifying, and well-researched film. But it is also a misnomer. Although Hirsch followed several victims of bullying throughout the 2009 school year to reveal to the world the problem in America’s schools, the actual bullies of the film are conspicuously absent, making the movie more of a sob story about the horrors of bullying than a real critique of the social system that enforces it.

The movie begins with teary interviews with the parents of Tyler Long, who killed himself in 2009 at the age of 17. Clips abound of parents David and Tina describing how much they loved their son and revisiting the day they found him hanging in his closet. Home videos of Tyler learning to ride a bike and blurry baby pictures, juxtaposed with his parents’ tears, set the tone for the rest of the movie: Bully’s main effect is to get viewers crying, not thinking.

Next, Hirsch introduces Alex Libby, age 12. Libby is an awkward boy who hasn’t quite adapted to puberty and has trouble interacting with his peers. Classmates call him “fishface.” They also punch him, strangle him, and sit on him on the bus. Viewers also meet Kelby Johnson, who has since come out as a transgender male but faced much ostracization and bullying in his hometown due to his sexual orientation, and Ja’Meya Jackson, who held her entire school bus at gunpoint after months of relentless verbal abuse. The film’s final character, Ty Smalley, was another suicide victim who was bullied in his final months.

With the exception of the video used to convict Ja’Meya and some footage of Libby’s bus ride torment, Hirsch shies away from actually portraying bullying or bullies. Instead, his film is loaded with interviews with students, parents and friends, and their responses are pretty uniform. They affirm that bullying is terrible. The parents cry that they want something better for their kids and bemoan the apathetic school system.

The students agree that what’s happening to them is pretty horrible, and make it feel even more unacceptable by laughing it off. Johnson tells a story of how a couple of her classmates tried to run her over with a minivan, then jokes that “it couldn’t have been something cool like a Jeep, could it?” Libby describes another disconcerting incident on the bus to his parents, but adds hurriedly that “I think they were just messing around.” The appalling treatment of these kids, combined with a casual attitude that makes them seem used to it, just further drives home the film’s only message: bullying is bad.

But do any of us really need that message? It’s a generally accepted fact that bullying isn’t exactly good, and while this film’s intense focus on the horrors of bullying may shame the minority who think bully victims just need to man up and punch their tormentors in the face, it’s not doing much for the rest of us. People who already abhor bullying get little out of the film but a reaffirmation of what they already know: bullying is a problem that needs to be stopped.

What they do not get is advice on how to stop it. Hirsch’s film gives very little insight into what concerned individuals can do to combat bullying in their schools, apart from emphasizing that school administrators are useless. The only character to fully escape her torment, Kelby, had to transfer to a different school in a different town.

And while the film does, obviously, point out the problematic epidemic of bullying, Hirsch’s failure to point to specific causes of the situation makes it easy for viewers to distance themselves from the issue at hand. “Those poor kids,” we can think, exiting the movie theater. “That was horrible. But that wouldn’t happen here.” Since Hirsch doesn’t point to bullies and bystanders as the real source of the abuse, it’s difficult for viewers to recognize their own behavior as bullies and bystanders.

It’s far too easy to dismiss bullying as someone else’s problem. Most of Hirsch’s subjects lived in Southern towns, far removed from places like Ann Arbor, and this makes the bullying issue seem far away and irrelevant to our lives. Community High School in particular is notorious for our attitude of “that doesn’t happen here” about bullying, especially of gay students.

But it does happen here. Bullying happens everywhere, and Ann Arbor is no exception. A survey in 2007 found that 84 percent of Ann Arbor Public Schools students surveyed heard derogatory remarks towards LGBTQ students “often to frequently.” And our self-satisfied insistence that such things aren’t a problem often just makes it harder for bullying victims to come forward and for bystanders to recognize bullying for what it is.

If we really want to stop bullying, both the subtler type we see in our own schools and the extreme examples Bully documents, we need to throw off our complacency. Instead of blindly pitying Hirsch’s protagonists, we need to look around our own schools for similar situations. And instead of simply sighing about the “epidemic” of bullying, we need to stand up and combat it.

That begins by looking inward. Just because most of us aren’t in the habit of shoving freshmen into lockers or shaking down third graders for their lunch money doesn’t mean that we’re innocent of bullying. We bully by laughing behind people’s backs in class. We bully with snide, witty remarks. We bully by ostracizing people who make us uncomfortable. We bully by turning a blind eye when our classmates do all these things and more.

If Hirsch were to fully portray the bullies in his film, would we see stereotypical dumb, muscled jocks searching for easy prey? Or would we see ourselves? If we really want to combat bullying and make its victims safe, it’s time we stopped passively bemoaning the issue and started looking it straight in the face. Only then will students like those in Bully feel safe and accepted in their own schools.

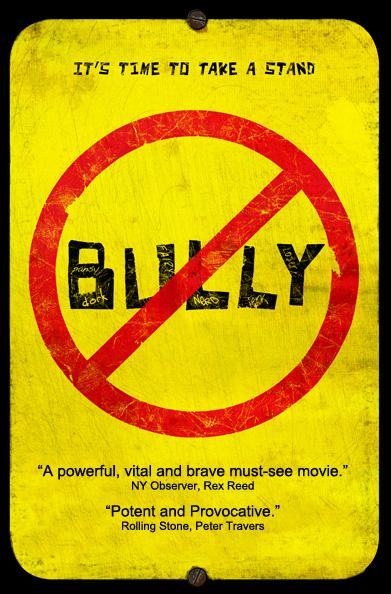

Image taken from http://thebullyproject.com/