“Rush” Is As Sleek and Engaging as It Is Philosophically Muddled

Some directors gain a degree of their reputation on the basis of sheer versatility; greats like Howard Hawks, Akira Kurosawa and their modern equivalent, Spielberg himself, are distinguished by both their remarkable variety in genre, scope and style and fairly singular thematic focus. Ron Howard, by contrast, may be one of the most undecipherable directors today — and oddly enough, one of the most popular. Just when he seems to be a dedicated provider of high-stakes adult dramas (Apollo 13, Frost/Nixon), Howard takes a bizarre sidetour into simplistic childrens’ film garbage (How the Grinch Saved Christmas), or abysmal Tom Hanks conspiracy dramas (The Da Vinci Code). Even after four decades in show business, it’s frustratingly difficult to get a grasp on where Howard is coming from, and worse yet, where he’s going much of the time.

Rush makes the quest to understand Howard no easier, but that’s only because it’s much more progressive than anything else in his oeuvre. Collaborating again with Frost/Nixon screenwriter Peter Morgan, Howard has crafted a biopic that’s surprisingly edgy and wickedly entertaining for the exact same reason — its protagonists, two real-life Formula 1 rivals, must literally cheat death every time they go to work. It is a job requiring both intense calculation and a loose, improvisational outlook on life, and Rush largely focuses on this disconnect.

The two protagonists, James Hunt (Chris Hemsworth) and Niki Lauda (Daniel Brühl) embodied clashing perspectives as well. At the peak of their 1976 powers, which Rush explicitly chronicles, the two represented wildly opposite ideologies, with Hunt being the carefree playboy counterpart to Lauda’s clinical, calculating professional. What unites the two, however, is their perverse comfort with deathly conditions, savage hunger to rise to the top of their field, and willingness to throw most other relationships in life to the wayside in order to succeed.

The young leads performing them, Hemsworth and Brühl, are uncannily good. Hemsworth’s calling-card to the role was his effusive charisma in the otherwise unremarkable Thor, and I can’t imagine a better output for his signature intelligent arrogance. Brühl, by contrast, is steely, intelligent, and is a genuinely intense, fascinating presence. His character, Lauda, is certainly more in line with the general philosophies that guide Rush; there’s a sleek professionalism brimming beneath the surface here, often driving forward the more kinetic sequences but somewhat diminishing any emotional impact.

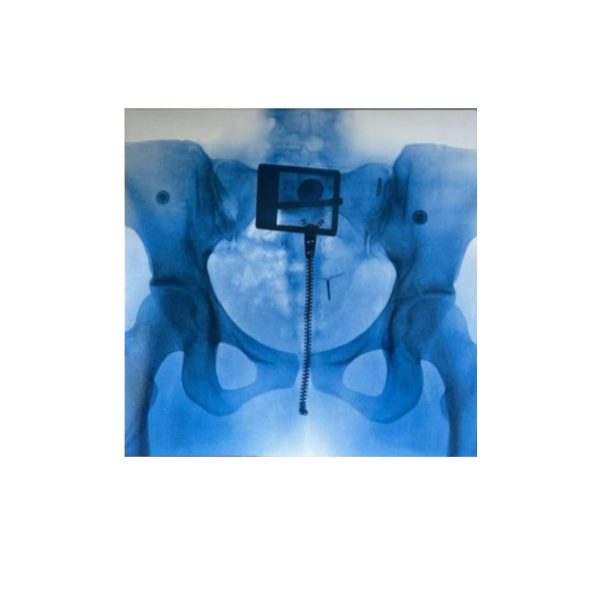

The film has to compress so many events into such a narrow timeframe that they’re often explained rather than truly evoked. One never gets much of a sense of triumph, loss, or connection to the protagonists and their achievements. It is only in Rush’s extended racing sequences that it transcends its emotional emptiness and becomes something else entirely — a manic, rapid, mechanical dance with death. Anthony Dod Mantle, one of the most adventurous cinematographers today, gives the film a deliriously colorful pop that is good enough to convince us we are watching events more thrilling than we are, especially when the characters are off the race-track.

But for all of the things Rush absolutely nails, it’s difficult to make out much of a guiding philosophy to the film. It presents two clashing belief systems regarding racing, life and death, and spends considerable time demonstrating they’re equally valid, but given that its director, Mr. Howard, has spent an entire career avoiding statements of major controversy, one doesn’t come away with much. Rush brings us ever-so-closely to the verge of major ideas and genuine contemplation, then speeds away.