Cull of the Wild

AAPS Media Specialist and Citizens for Safe Deer Management Co-founder Jeri Schneider spoke the minds of many Ann Arbor citizens when she said she was “shocked and appalled” at Ann Arbor City Council’s 8-1 approval of a deer cull program on Aug. 18. It was an important turning point in an ongoing struggle to deal with Ann Arbor’s increasingly prevalent deer problems.

Perhaps “deer problems” is a bad way to put it. Schneider pointed out that the issue at hand is less of a “deer problem” and more of a “deer-human conflict,” highlighting the

importance of figuring out how to coexist with deer as opposed to getting rid of them. Her organization is opposed to a deer cull, or an organized killing of deer as a population reduction technique, in Ann Arbor.

The question of deer management was first raised several years ago, when a group of Ann Arbor residents came to City Council with concerns about their landscaping being eaten by deer. Since then, several other deer complaints have received relatively little public attention, never resulting in any major decisions. The recent push for a cull stems from reports of increasing deer populations, although such reports are not supported by actual data and are purely anecdotal.

Other than consumption of vegetation, there are several reasons why people support a cull. For one, they often claim that deer increase the spread of Lyme disease, although Schneider pointed out that this is not necessarily the case. “When you look at a map of the deer populations in the state versus a map of the Lyme disease instances, there’s no direct correlation,” she said. “There have been studies done where they’ve done deer culls and they’ve tracked the incidents of Lyme disease in those areas, and the results have been mixed. Some have shown that by culling deer it has reduced the incidence of Lyme disease, but others studies have shown no change.”

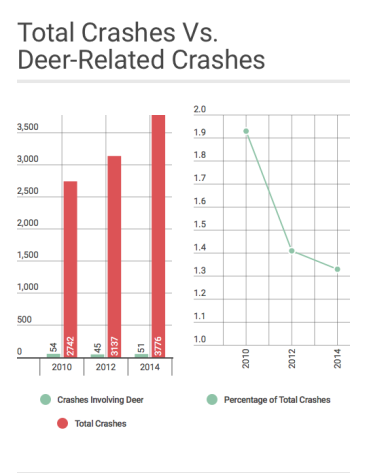

Another common argument for a cull is that the number of car collisions involving deer has been increasing, although this seems to be false as well.

It seems that the number of deer-related car crashes is fluctuating. Even if there is an upward trend, it is clearly in accordance with an increase in the total number of crashes, to the point that there has been a general decrease in the percentage of total crashes that are deer-related.

A major criticism of a deer cull is its cost. For this year alone, $90,000 have been authorized for use in culling; this includes the cost of scouting the area where a cull will occur, the cost of laying out bait several nights in a row, the cost of public engagement (public meetings about the issue), the cost of aerial deer counts throughout the winter and the cost of actually hiring sharpshooters to come and shoot deer. Furthermore, a cull is not a one time solution. As Schneider said, “There are a number of places where they do culls, and they have to repeat the culls year after year after year after year because it never really reduces the population.”

So what is the alternative to a cull? “Non-lethal” is a broad term that includes all possible methods of reducing deer-human conflicts besides culling. There are two categories of non-lethal methods: birth-control methods and changes to the behaviors and policies of the people or the city.

Methods other than birth-control, which don’t involve direct changes to the deer, are often ignored due to their lack of immediacy. The reality is, however, that if citizens of Ann Arbor wish to have a long-term solution to the current deer-human conflicts, there may be a need for long-term methods of solving them. These methods include putting up better signage to alert vehicles, using scare tactics, building fences and removing vegetation from the sides of roads, because deer don’t like wide open spaces. Still, while these methods may aid in resolving deer-human conflicts, it is unlikely that they alone would be employed as solutions.

There are two main ways to sterilize a doe. One is through injection of the porcine zona pellucida (PZP) vaccine, which, if successful, makes a doe infertile for one to three years. The PZP vaccine is still in an experimental stage throughout the country, and has an unfortunately limited success rate.

Perhaps the most plausible non-lethal method is ovariectomy. Ovariectomy has a greater up-front cost than injection of the PZP vaccine, but it only has to be done once, and it has a nearly perfect success rate.

No method of deer sterilization is well-tested and certain to work, but there’s no reason that Ann Arbor can’t be the first place to test it. This is what Christopher Taylor, Mayor of Ann Arbor, pointed out. Taylor cast the lone dissenting vote on the proposal for a cull, and he did so partly due to a feeling that non-lethal methods had not been sufficiently explored. “There are no broad studies analyzing and seeking to deploy non-lethal birth control methods in an environment such as ours,” he said. “We have not tried to explore whether we can get such a study off the ground, working with DNR [Department of Natural Resources] or a principal investigator from, say, MSU, or some similar institution in the state. I’d rather we give that a shot before moving to a cull.”

Why, then, with so little research done as to whether non-lethal methods are possible, did eight City Council members vote to approve a cull? Taylor explained his take on their stances, saying, “They’re not bloodthirsty folks. I think they concluded that the deer are negatively affecting our natural areas by their consumption, and that the only way to effectively reduce their numbers is through shooting them. They would take the position, ‘Look, I’m sorry. I would rather there be no cull. I would rather nonlethal methods be successful. But,’ they would say, ‘they’re not proven, so we have to take a choice, and the choice is to be effective or not effective.’”

The main reason Taylor voted against the proposal, however, was that he felt there was an “insufficient community consensus” on a cull. Ultimately, Ann Arbor citizens’ views are what matter the most, and there are a variety of things citizens can do, independently of the city, to try to ease deer-human conflicts without having to kill any deer.

First of all, people can avoid feeding the deer. City Council recently passed an ordinance that makes deer-feeding a civil infraction, but if not to avoid a fine, people should avoid deer-feeding because it makes deer feel more welcome in neighborhoods, causing the sort of deer-human conflicts that made culling an option in the first place. People should feel free to resort to scare tactics; if a person has an unwanted deer in their yard, they can admire its beauty, but then chase it away so it doesn’t come back.

People can “deer proof” their yards. The obvious way is to put up fencing, but there are other ways as well. Certain aromatic plants (like sage, thyme, lavender, etc.), when interspersed throughout a garden, tend to repel deer from that garden. There are also deer-repellent solutions that can be purchased and applied to gardens to repel deer, although they have varying levels of success.

Most importantly, people can contact their city council members and let them know whether or not they support a cull. They can write comments or letters to editors of deer cull related articles on MLive.com, with hopes of getting their views published. As Taylor said, “This issue is very deep-seated with many people. The notion of shooting animals in the city affects people very deeply.” In an issue as important and controversial as the killing of deer, it is essential that people speak up to ensure that their City Council members make the decision that most supports the views of their constituents.