The Hikone Exchange Program

In the fall of 1979, a woman named Rusty Schumacher traveled to Hikone, Japan for the first time. She worked at Clague Middle School in Northeast Ann Arbor and was sent overseas for six weeks in order to learn about Japanese culture and spread it throughout the Ann Arbor area. Once she returned, she joined forces with the rest of the Clague staff and spent time sharing various items she had collected while in Japan. Most of these included Japanese food and stories from her trip.

Schumacher had one main dilemma after her trip; she wanted students to experience Japanese culture rather than just hear about it from her. “I can tell you about Japan and what it’s like, but it’s so much more real if you can experience it for yourself,” Schumacher said.

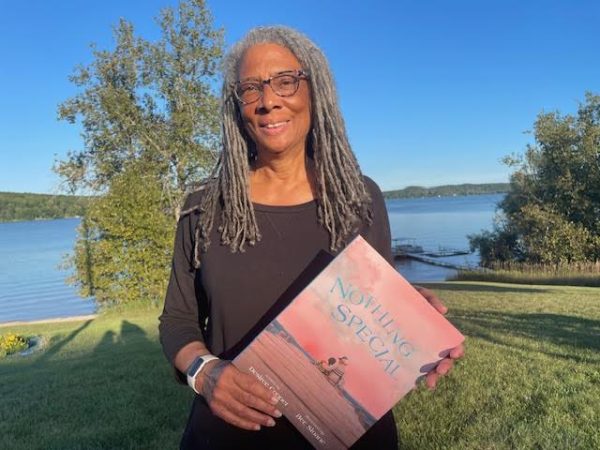

Schumacher hasn’t been to Hikone since 2005, but she still is connected because she started the program. She has a special connection with each individual that went on the trip.

At first, Schumacher was providing the money for the students to travel. Eventually, students had to start paying and fundraising for themselves. In the beginning of the program, students would travel to Hikone in the summer for 17 days. Summers in Japan can get up to 85-90 degrees fahrenheit, so the trips began to occur in the fall.

A Hikone Castle tour guide holds a drawing of the old view outside the Hikone Castle comparing it to the current landscape of the town below.

No trip is the same; they alter which historical landmarks they visit. It varies from ancient temples where emperors lived to where the military fought to where an important figure had lived. Every year there are new host families too. Usually the students that get picked to do the exchange will get paired up and host each other in their home country.

Since 2015, Annette Ferguson has been the Business Partnerships and Volunteer Coordinator for the Hikone Exchange Program. Every two years, 14 students and two teachers travel to Hikone and 14 students and two teachers from Hikone come to Ann Arbor. In 2016, nine girls and five boys traveled to Hikone. In exchange, also nine girls and five boys traveled from Hikone to the United States. They got to travel around in a yellow school bus. “They were excited to go on a yellow school bus to travel,” Ferguson said. “They wanted to ride the bus again.”

Students from Hikone and Ann Arbor are very similar. In Ferguson’s opinion, they both are curious, excited, independent, mature, gracious and outstanding. These 14 students were picked to travel 6,508 miles to experience the culture and language of another country, half-way around the world. They were timid about the language that is not their first and their confidence grew just by speaking it. It also grew by just knowing that they had ventured out into the world. “Every trip is different,” Ferguson said. “Purposes are very different, but it affects people in roughly the same way.”

In order to participate, students filled out an application and completed a video interview. They also had to commit to fundraising, the cost and the classes, which took place every Wednesday from June to November. Then, a committee assembles to review these middle school candidates. “We look for students who express independence, maturity, curiosity,” Ferguson said. “We look for representatives of the district.”

Ann Arbor has sister school relationships between its schools and the schools in Hikone. Two students are chosen from each middle school, therefore, two students will visit each school.

The most recent delegation traveled to Japan from Nov. 6 through Nov. 18, 2016. Among the 14 middle schoolers was 14-year-old Loey Jones-Perpich. She wanted to travel with the program since she loves to travel and she feels it’s more interactive to travel with an exchange program than with her family.

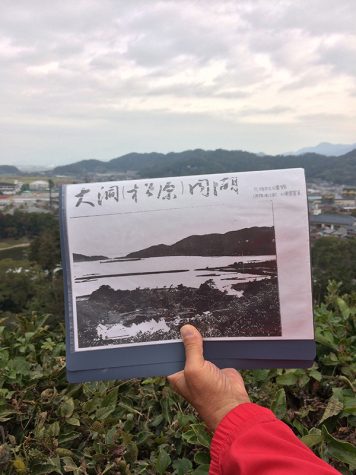

The three story Hikone Castle in its original hill-side location.

“Japan in the back of my mind has always intrigued me and it just seemed like an awesome opportunity,” Jones-Perpich said.

“There was this whole application process where you had to fill out all this personal information,” Jones-Perpich said. “I had to write a paragraph about my hobbies and a paragraph about my experience from people from other cultures. I had to write a full 500 word essay about why I was a good candidate for the program and I had to get two teacher recommendations.”

After all that, she was interviewed by Ferguson. She asked the finalists a couple questions and filmed them in order to show other people on the board. Once Jones-Perpich was officially selected, she had to go to classes over the summer to learn the language and the culture of Japan.

“There was a lot of mental preparation,” Jones-Perpich said. “I had to fundraise $600 and we folded 1000 paper cranes. We learned about things not to do and we prepared a musical presentation that we did while we were in Hikone.”

“We’re not allowed to ask to go to Tokyo because it’s too expensive and too far away,” Jones-Perpich said. “If you imagine Tokyo as New York, Osaka is like Chicago.” Jones-Perpich’s host family took her to Osaka during one of their personal days to experience a big Japanese city.

The delegations usually have set schedules when they travel. They are in Hikone with host families for a week and then have a week of group traveling time. During that travel time, they take trains to Hiroshima, to an island off of Hiroshima called Miyajima which has a huge famous shrine and to Kyoto, another big city in Japan.

The Miyajima world heritage shrine, taken on Miyajima Island in Hiroshima.

One thing that Jones-Perpich learned from the program was that people in Japanese schools try harder. “There’s a test to get into high school so everyone wants to be there,” Jones-Perpich said.

“I go to Skyline and 600 of the 1600 students don’t want to be there and don’t try and every single student at that middle school in Japan wanted to be there and they tried their best.”

Among the 14 students in the 2014 delegation to Hikone was then 14-year-old Emma Cooper. She heard about the program through her school when they were looking for extra host families. Cooper, now a junior at Skyline, remembers feeling very honored to be selected from the large group of finalists. “There were seven or eight people applying from my school and only two get selected so I felt really lucky,” Cooper said.

Cooper had to take language and culture classes in the summer leading up to the trip. She learned how to speak Japanese and other interesting facts about their culture. Her favorite thing that they did in preparation was going to a sushi restaurant and trying an eight-course fully extensive Japanese meal.

“It was so good, I ate so much,” Cooper said. “We tried all these different things like beef tongue, which I never actually encountered in Japan, but I got to try it.”

Packing was one of the hardest parts for Cooper, since they had to bring gifts for their host families, pack enough stuff to live for two weeks and still keep enough room in that suitcase to be able to take stuff home.

“Thinking about what I needed to bring and not bring was really important,” Cooper said. “We had to wear uniforms at the schools [and] our host students brought us our own outfits.”

The delegation also had to make sure that everyone had their passports, birth certificates and all of their legal documents ready. They had to exchange currency, making sure they had enough Yen for the trip.

“My parents set up a credit card at that time for emergencies, but that wasn’t required,” Cooper said.

Cooper feels that the time spent at Hiroshima was one of the the biggest points of the trip. “We really got to reflect on how our being able to come to Japan is promoting the whole idea of peace between our countries and that was a really touching moment for everyone,” Cooper said. “It really put everything in perspective.”

The most important lesson Cooper learned was the friendship she found with her host sister. “Friendship between two places that were once in conflict was so unifying,” Cooper said. “It highlighted the importance of being friends with people and how those relationships can last forever.” She became very close with her host sister and still emails her once or twice a week. Even though Cooper hasn’t been to Japan since the trip two years ago, the two families still exchange Christmas cards.

A view of restaurants, businesses and shops along the Dōtonbori River running through Osaka.

Communication was hard for both Jones-Perpich and Cooper. Jones-Perpich talked to her host family through very simple English. She used google translate a lot and writing the words down seemed to make it easier for her family to understand what she was trying to say.

“I had to really condense the things that I wanted to say and sometimes I just gave up on trying to say something because they just didn’t get it,” Jones Perpich said.

Cooper knew a little more Japanese when she traveled to Hikone. She communicated with her host family through Japanese when she could, and English to fill in the blanks. In Japan, the students start studying English when they’re very young, so her exchange student’s English was decent. When Cooper’s Japanese wouldn’t make it she knew she could communicate with them in English.

This made Cooper think about how Americans don’t really focus on other people’s cultures in their own schools. She feels that American schools should focus a lot more on foreign language.

“[America] is not superior to anyone so our language shouldn’t be,” Cooper said. “It’s hard for exchange students just being in a place where everyone expects you to understand everything but you don’t.”

Cooper’s favorite part of her trip was traveling with the delegation. In Kyoto, the delegation went to the restaurant at the top of the Kyoto tower.

“We got to look out over the whole city and it just hit me that this is an amazing place with amazing people,” Cooper said.

Jones-Perpich also really enjoyed traveling with the group. Time with the host families took up most of the trip, but Jones-Perpich loved traveling with her delegation.

“My two favorite days were the days we went to Miyajima and Kyoto,” Jones-Perpich said. “In Miyajima, we took a ferry out to the island and we just had a couple hours and we got to explore. In Kyoto, we [took] a bus tour and then [went to a] temple where they have 15 rocks in a rock garden and you sit and you look at the rocks. [People in Japan] believe that the rocks are holy.”

“It was scary but it was probably my favorite time from [a] high school related activity,” Cooper said. To her, it was special simply being there with all of her friends and the people that she met while in Hikone. “All of them were just amazing people that I never would’ve met if I hadn’t done this,” Cooper said.

“I grew as a person, especially going to Hiroshima,” Jones-Perpich said. “I saw the world from a different set of eyes.” After the trip, Jones-Perpich didn’t know how to wrap her mind around the fact that the program wasn’t happening anymore. “It was back to reality and that kind of sucked. I lived Friday, Nov. 18 twice,” Jones-Perpich said. This refers to the 14 hour time difference between Hikone and Ann Arbor.

The only building at Hiroshima that wasn’t completely destroyed on Aug. 6, 1945 by an American B-29 bomber.

“The exchange program is mainly administered through the school district, but the city does provide a certain amount of moral support,” said Christopher Taylor, Mayor of Ann Arbor. C. Taylor is both the mayor and a parent of two kids in the Ann Arbor public schools. He has been involved with the program since 2012 when he was on the city council. In 2016, he was asked to welcome the students and teachers from Hikone at Tappan Middle School. “My role as mayor was to give a short welcome speech that was suitable for translation and then to personally greet them,” C. Taylor said.

C. Taylor has never been to Hikone himself, but he has traveled out of the United States to Canada and Europe. He wishes to someday travel to Asia, perhaps with a program such as this. “It makes sense to go in capacity of the mayor with a formal exchange program,” Taylor said. “It would certainly provide a structure for me to be [in Hikone].” Going through a program opens up new opportunities for individuals to experience a culture.

C. Taylor believes the students get four major things out of the program. First, they learn about the process of applying for something. Second, those who are fortunate enough to be selected will learn about long term preparation for a goal. Third, students get to learn another country’s culture and language. And fourth, they have the opportunity to see a culture that is so different from their own in a very personal and extended way. C. Taylor sees values in our community of openness, engagement, welcoming and interest of learning about others languages and cultures.

C. Taylor’s daughter is friends with Jones-Perpich. He had been to Jones-Perpich’s home to pick up his daughter and had the opportunity to meet Mizuka, her exchange student. As a parent, C. Taylor talked to his kids about whether it was something they were interested in or not. “Even if your child didn’t participate, you get the opportunity to raise the question with you child,” C. Taylor said. “They get a sense of options that they have and if it’s something they want to pursue or not.”

In 2014, a two hour documentary named “The American Ambassadors to Japan” was released. It was produced by Tim Negae. It featured the group of 2012’s ambassadors who traveled to Japan and the students from Hikone who came to the United States. The 12 students that were chosen to be ambassadors were Chad Aaronson, Nathan Campain, Matthew Ferraro, Sophia Klein, Marrisa Modell, Vanessa Noble, Miranda Reed Twiss, Kenneth Simpson, Mia Sowder, Chris Schweitzer, Jane Taylor and Hannah Zonnevylle. The students from Hikone were left unnamed.

In the documentary, it shows the classes these ambassadors had to go through so as to learn new language and culture. It also shows what it was like in 2012 to have an exchange student stay in your home and go to school with you. Later on, it displays the ambassadors traveling to Hikone and visiting Hiroshima.

In the movie, they exit a train station and run into some vending machines, receiving a variety of reactions that showed how these ambassadors reacted to things they have never seen before.

“They were very colorful,” J. Taylor said.

“It was the first thing we saw,” Schweitzer said.

“You never see a vending machine that serves coffee and alcohol before,” Simpson said.

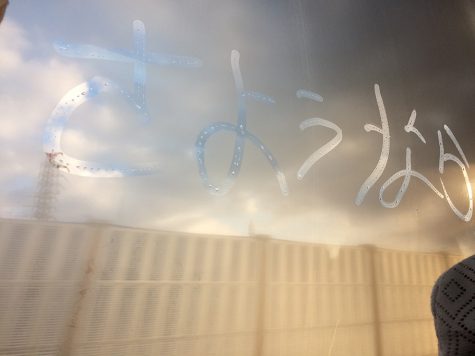

Near the end of the movie, you can see the emotion in these students having to say goodbye to the person they have lived with for one week. There was crying, hugging and picture taking. They also had a ceremony in which they gave speeches in Japanese to the host families and Hikone representatives. They performed a song in English that well represented American culture, followed by a song in Japanese to show what they had learned.

The Hikone Exchange Program wouldn’t be possible without the support from the Mayor’s Office, the University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies, the University of Michigan Language Resource Center, the Japan Business Society of Detroit and a number of local businesses in Ann Arbor. These local businesses help with providing gifts for those in Hikone. “Gift-giving is an enormous part of [Japan’s] culture,” Ferguson said. “[There are only] a number of things that could fit inside a suitcase and travel with them to gift them when we got there.”

Other than Hikone, Ann Arbor has five other sister cities including Tubingen, Germany; Belize City, British Honduras; Peterborough, Ontario; Juigalpa, Nicaragua; Remedios, Cuba and Dakar, Senegal. These sister city relationships are established by friendship and peace.

“It is much bigger than the fourteen kids,” Ferguson said.

Japanese letters on the window of a train that read “sayonara” in English as the 2016 Ambassadors leave Nagoya on the way to the airport.