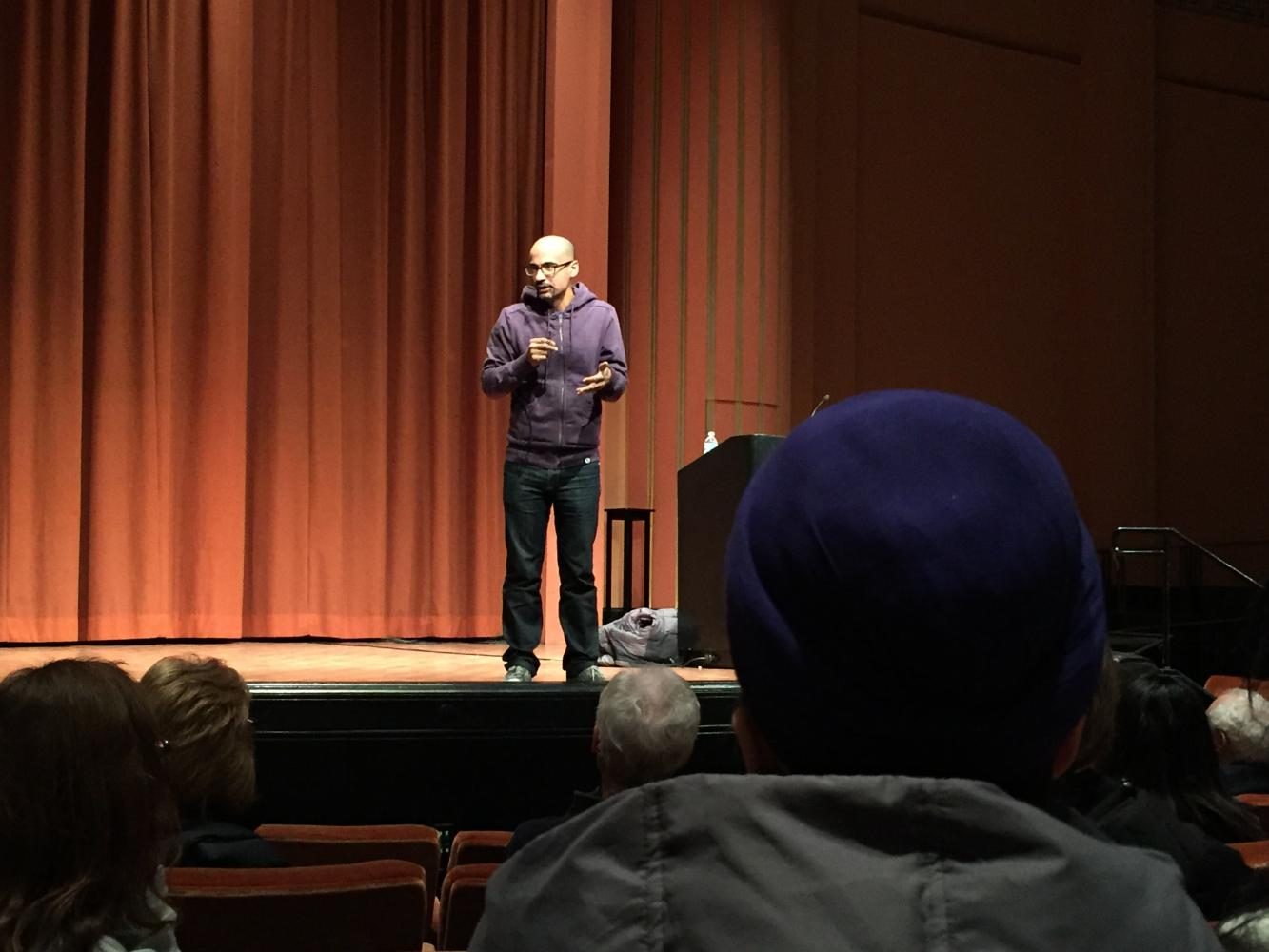

No Dreams Of Transcendence: An Interview With Junot Diaz

You speak often about decolonized love: the search for a love that transcends colonization and patriarchy. Have you ever experienced it personally? I don’t believe in these things — that you can transcend. I think that that’s the way that these structures perpetuate themselves. The best way to keep patriarchy alive is to dream that you can transcend it. I just don’t believe it. I think that this is going to be in our relationship, and for me [if] it’s going to be in our relationship we should try to be honest about it and we should try to manage it and try to reduce it. Dreams of transcendence, that’s like dreams of transcending life. From what I see that’s not gonna happen. We’re not gonna live forever, life has got its price and I’ve always been someone who’s more inclined to live life by life’s rules, which is to understand that I’m in no position to transcend its most terrible demands. Learning to live with these things is, for me, more hopeful, more practical and more realistic and less fantastic than saying that I can transcend them. I think it takes a lot more to admit to oneself that these ideologies, these social forces that hold us and bind us will not be so easily evaded. I find it much easier to recognize that and work at that level, but to each their own.

Do you think there’s a point in imagining things in a not-so-negative way or do you find hope in imagining what civilization would be if colonization never happened? Sure! That’s utopic and there’s value in everything. There’s value in imagining, what if women had never been enslaved by men? I think these are important fantasies and important sort of thought experiments. I don’t find any problem with it. There are multiple tactics for all of the things we aspire to, and that’s certainly a legitimate and viable one.

Why does your narrator Yunior, though he manifests sexism in many ways and contends with sexual assault in many ways, never cross the line into committing sexual assault himself? That’s not who my narrator is. My narrator through all three books is a character, Yunior De Las Casas, who is a product of the kind of mainstream masculine socialization both in the Dominican Republic and Central New Jersey. And he sort of expresses a lot of fucked up patriarchal thinking that comes along with this kind of socialization. But from everything I’ve understood about his character, there’s nothing about his experience that makes him capable of sexual violence like that. Sure, he’s capable of a bunch of other crap that in fact falls into the spectrum of patriarchal practices, but all of us exist in a spectrum and we all draw our lines and that’s not his bag. In fact, there’s something about his careful documentation of rape and sexual violence in his communities and within his circles that perhaps indicates why this might be a crime too far for him.

How does growing up in New Jersey impact your writing? It’s hard to say. It’s had a huge impact but we never know because we have no map of our interiority; we have no quantification of our unconscious or our soul. We only have intuitions. I sense that the space and the culture of New Jersey, my New Jersey as opposed to anyone else’s, was indelible in shaping me. It had an indelible impact, but I’m not sure I could exactly describe where that begins and where that ends. I’m very much interested in writing about New Jersey and setting my stories in New Jersey, so clearly I’ve developed some devotion to this crazy ass state. What exactly it means? I think that is something the work itself attempts to answer and to wrestle with. There’s no shorthand for that, there’s no A-B-C-D. I think if I could answer what immigration or what New Jersey slash America means to me, I wouldn’t have to write.

What would you tell someone who’s overwhelmed and hurt by the election results and oppression sects of this country perpetuates? It’s always going to victories and there’s always going to be losses. This is a particularly grievous loss. I think we can’t sugarcoat it, this was a thunderous blow to many of us. But, the truth of it is we are really gonna win some and we’re gonna lose some. For me, as someone who did community work, every time I was dealt a huge loss it worked out better when I got through the gloom sooner [rather] than later. If I became entirely disheartened for a long period of time that’s a self-fulfilling prophecy in some ways. I kept reminding myself that ultimately, we have no idea how any of this is going to end. Therefore, we have to have an enormous amount of faith that even when things turn incredibly dark that our work really matters, that this is not going to be just futile. That faith has to be clung to. That helps, that helps, but there’s no way to sidestep the agony of defeat. That’s not gonna happen so you better metabolize that as soon as you can. There’s no way to make it any less; this one was like falling out of a ten-story building. Every part of you feels broken. You gotta metabolize that. If you can do it productively, not blame yourself, not blame your community, not become bitter, not fall back into confusing or demoralizing and demotivating fiction, all the better. If you can cleave towards your friends and to your collectivity and your higher values, all the better. If you can keep working through the darkness, all the better. Not always easy, but I think it’s perhaps worth aspiring to.

Is your activism different than how it was in college in regards to how it is now? I hope so. I mean if, shit, if we’re supposed to be static our whole lives, that sounds horrible. Everything has got its time and everything has got its season. Some people have different trajectories for it. I’m looking at 48 years old. I have a lot of friends who I came up with as activists, and you know, you’ve got to try different things. You have to try different things. You don’t have the same time and the same sort of space at 48 that you had when you were 18. That’s not going to happen. You’ve gotta stay to your strengths. I’ve got friends of mine who’ve got kids and things will get altered. I’m not sure that it’s only young people are really fired up and older people are laying down. I’m not sure that’s actually always the case. I do think that young people’s energy is extraordinary. It’s one of the great gifts of being young, this tremendous creative vitality. [It can’t be] falsified or duplicated or recreated. It’s just an extraordinary gift it gives to many of our movements. But again, we need it all. We need people who are kind of sober-minded, we need people who are absolutely splenetic. We need folks who are kind of long and deep thinkers, we need folks who are much more reactive and passionate. I’m about it all.

I always had a wide community when I was at Rutgers. It wasn’t just organizing with college students. There were folks who had been in the game for a really long time and there were folks, who themselves were only like part time activists and there were people who that was their entire fucking life. They were like lifestyle activists. I got access to a whole wide range of ways that one does community work. I was actually very cool. Well, not that I was very cool, I was cool with it. I wanted that diversity. When people would try to sell me that there was only one way I’d be like “Yo, you scare me.” I’m not looking for progressive orthodoxy. It’s bad enough I got fucking oppressed by a hegemonic orthodoxy that tells me, “You’ve got to be one way and do things one way.” That was tedious and soul breaking enough. I don’t need that from the progressives. I don’t need litmus tests and tests of authenticity and tests like, “Are you woke enough?” That shit is boring. And the people who are tempting to impose that tend to people who themselves have, I would argue, real questions about these things inside of themselves and they’re externalizing them. They’re sort of discharging them on other people. I saw that coming up, and I was always much more happy with a heterogeneous community and the debate between strategies. I never liked it when one strategy would “win”. I don’t think that’s the way it’s going to work.

Do you ever find yourself looking at someone as an authority? Shoot, I got nothing but authorities man, I mean, of course! There are so many people who I see that inform not only my critical and artistic sensibility but they provide guidance and mentorship, who stand as kind of archetypes or tribunes of a certain kind of excellence, or moral fiber, always. Who doesn’t have that? Myself, I’m not really interested in not particularizing where my insights come from, and not underscoring that none of this is meant to be universal. It’s meant to be just part of a conversation. In fact, the more particular you make it, the more I would argue, the more space you make for other versions. I don’t imagine that this is the only version. I do sort of take pains to try to make sure to be clear on that. But, no, I mean, god, I could list all day long, from Arundhati Roy, to Samuel R. Delany, from Octavia Butler to Tananarive Due, from Oscar Hijuelos to Francisco Goldman. There are so many people who I consider authorities in multiple areas.

Do you think that growth happens as a gradual process or are there moments in your life that changed the way that you look at people? I hope so. There’s all sorts of things. There’s gradual, there’s episodic, there’s invisible, where you don’t even know what’s happening, you don’t even know you’ve changed. And then there’s these inflection points, or these points where something, everything feels like it absolutely alters. I think there’s multiple approaches to the way people evolve and change. And there’s some people who claim that after a certain age they became the person they were and they’ve never changed. Okay, I believe that too. It strikes me that all things are possible, but not all of us experience the same thing. I think there’s people who’ve experienced multiple deep shocks, and other people who have not. I mean shit, I definitely could point to two or three moments for myself where I feel like my life changed irrevocably.

Would you mind sharing? Why? They’re just so personal. I’m not sure I completely understand them myself. But you know, my brother being diagnosed with cancer, my family spending the rest of my childhood coping with that, that’s certainly one of them. Immigrating to the United States, that’s certainly one of them. I think most people have them. I think enough people in the United States have them that I don’t always feel terribly alone.

What do you think the work is of a journalist or an artist or anyone who’s trying to make sense of, or contextualize Trump and his presidency is going to be? I don’t know, because we don’t know exactly how horrible this is going to be. We know it’s going to be horrible. The exact extent of the horror? Still not available to us. I think that this is going to challenge our endurance. It’s going to challenge our ethics. There’s no question of that. I use context not to minimalize the challenges that face us, but to remind us that this is connected to a long arc of struggle. Yeah man, we’ve had defeats before. Are they this particular defeat? Hell no. Hell, no. From Obama to Trump? That’s some fucking shit. So, you know, the past can guide us. But we need to experience the trials ourselves, and we will be tested.

As far as I say we need to speak to young people. We do the best we can to remind them that we’re here as a community and we’re gonna fight to defend everything that we stand for and that we have come a long way and our victories are not as easily erased as all these people would like us to believe. The other side won and now they’re trying to demoralize us and throw us off our game. I’m like yo, this shit sucked, it was a tremendous loss, but I’m not seeding the ground. I’m not seeding the ground. And I tell my godchildren, “Listen, they won last round. They ain’t gonna win the game. We got this one. It’s gonna take a while, and we’re gonna fight it, but we got it, and you’re safe, I love you, we’re here for you. No matter what happens, we’re gonna be together.” And there’s very little else that you can ask for in life.

Junot Diaz is the author of the critically acclaimed “Drown”; 2008 Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award winner “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao”; and National Book award finalist and New York Times bestseller “This Is How You Lose Her.” Born in the Dominican Republic and raised in New Jersey, he is the current fiction editor at Boston Review. Diaz is the Rudge and Nancy Allen Professor of Writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of Barack Obama’s favorite writers.

This interview has been edited and condensed.