Changing Course from Calculations to Cinema

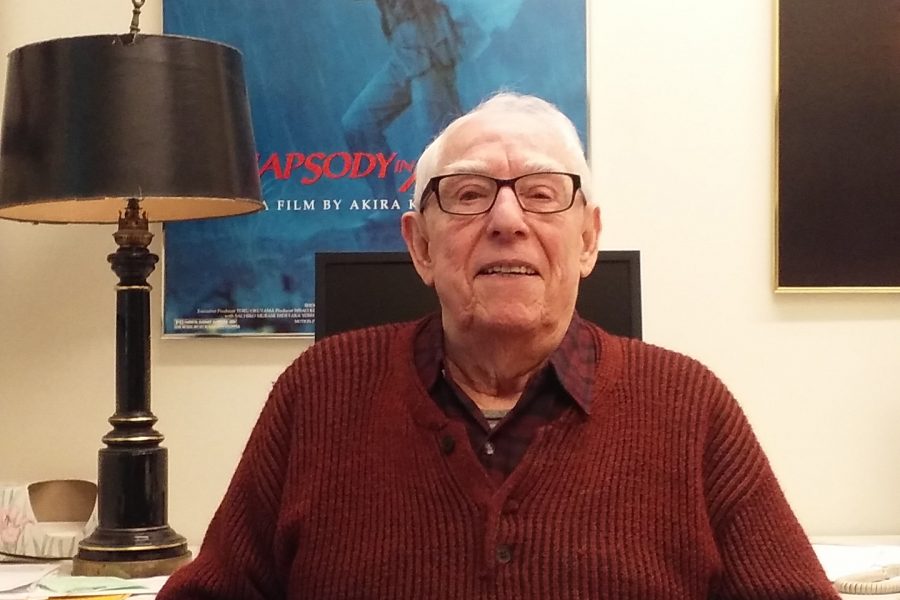

Hugh Cohen never imagined he could make films.

He did, however, love watching them, and had for years. “And love turned into an academic career,” Cohen said.

Cohen has lived in Michigan for his entire life. Growing up in the Detroit area, he attended undergraduate at Wayne State University. As a graduate student, he moved to the University of Michigan, where he quickly decided on a career as a teacher.

He became a teaching assistant, for some time, but had to get a job soon after — running out of semesters as a TA (teaching assistant). So where did this budding literature and film teacher go to work? The Engineering College. “I found a job in the engineering college…teaching in their humanities. At that time it was called the Engineering English [Program].”

All this time Cohen had been seeing films. As Cohen said, “In the 1960s and 1970s, the University of Michigan was a great place to see films: two different films a night, and a place called the Cinema Guild and several other film societies.” This constant film watching soon led to a job as the Faculty Advisor to the Cinema Guild Group.

“I was there and seeing films constantly, and I’m teaching in the humanities department, the engineering college, and I decided at that time, why not? Seeing I love films so much, why not develop a film course?”

The 1970s and 80s was an ideal time for a film course. Before this, film was considered like “comic books at the University of Michigan, it really was looked down upon,” Cohen said. But this attitude was slowly changing. Across the country, people were starting to appreciate films as an art form, and consider them on the same academic level as novels, as they expressed similar ideas.

This shift in attitudes came for many reasons, but Cohen attributes much of it to foreign films coming over from Europe: films like two he likes, The Seventh Seal, directed by Ingmar Bergman; and The Bicycle Thief, directed by Vittorio de Sica. “[These films were] dealing with different subjects, examining relationships in a way that American films weren’t, examining the countries and the life of people after the second World War in a way that American films weren’t,” Cohen said. And thanks in part to these provocative European films, the idea of film as an academic subject began to be taken seriously.

Cohen was not the only one at the university to have the idea. At the time, many teachers wanted to use film in their courses, but when they did, they were always forced to backtrack, and teach students how to look at and evaluate films, so the students could understand what they were looking at. “[So] we all joined together, and we went to the Dean at that time, and we told him we wanted a program in films.” He said yes, and so the Screen Arts and Cultures (SAC) program was born.

In the new film program, Cohen took charge of the intro course: the class teaching students about film language and history. He continued teaching this course for decades, until others took it over and he moved on to other courses in the last several years.

Over his long career, he has noticed some shifts in the films he loves. “They’ve become more varied,” he said. Documentaries, which used to have very little audience, now have TV and a more receptive audience for an outlet, and “documentary has really grown as a major art form,” Cohen said.

As for changes in the students he teaches? “More and more students come into this department because they want to make films,” Cohen said. These students want to go commercial, and to become writers and directors. They’re taking it not just as a humanities course, “but in preparation for a job afterwards, what they’re going to do for the rest of their lives.”