The Pepsi Navy

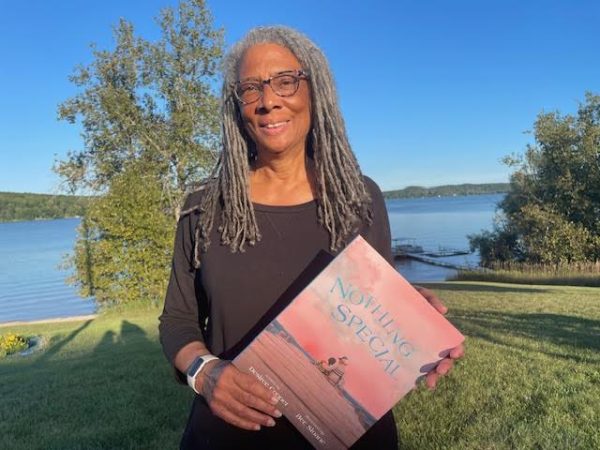

From left to right: Soviet Premier Khrushchev, Vice President Nixon, and Donald Kendall (later Pepsico president)

President Dwight Eisenhower knew that the United States was great. He knew that Soviet citizens would envy what Americans took for granted. So in 1959, he decided to support the American National Exhibition, a showcase of American middle class life in the middle of Moscow, after the Soviet Union sponsored a similar exhibition in New York City.

This was not only an exhibition of American life, though. It was also an example of cultural diplomacy against the Soviet Union, showcasing middle class housing, appliances, and cars that Soviet citizens would never be able to own, compliments of a failing political and social organization system.

The high point of this tension occurred at the Kitchen Debate between Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and Vice President Richard Nixon, which took place in the middle of the kitchen of a model American home. It was recorded in color and later broadcast in both countries. And, during one of the debates, a thirsty Khrushchev was handed a cup of Pepsi by an employee, Donald Kendall.

The picture of the premier of the Soviet Union enjoying a cup of Pepsi was great for business, and it planted in Kendall’s mind the possibility of selling Pepsi in the Soviet Union. However, it wouldn’t be until 1972 that he had the chance.

After Nixon was elected president, Kendall, now the president of Pepsico, used his political influence to strike a trade deal between the two countries and export Pepsi. However, they ran into an issue. The ruble couldn’t be exchanged in the international market, and the Soviet Union did not have any other currencies. How were they to pay?

Well, they might not have had money, but they did have vodka. In exchange for the Pepsi, the Soviet Union would pay with Stolichnaya vodka. Therefore, Pepsico broke into the alcoholic beverages market in the United States as the exclusive importer of Stolichnaya, and Pepsi became the first Western product to be sold in the Soviet Union.

Although Pepsico was making a profit, the total consumption of the Soviet Union, about 40 million cases, was about the same as the Orlando, FL metropolitan area. Bad roads, a lack of trucks, and bottling in cumbersome glass bottles meant that most of that inventory was consumed within 20 miles of the bottling plant. Pepsi wanted to do better, starting with introducing disposable aluminum cans and plastic bottles, reducing delivery costs and freeing scarce trucks for carrying useful goods instead of empty bottles.

In 1989, the agreement was about to expire. There were 20 plants bottling Pepsi in the Soviet Union, and they wanted to add 30 more. The new trade agreement was worth over three billion dollars, and the Soviet Union didn’t have enough Stolichnaya. What did they have, though?

Military equipment. The Soviet Union offered 17 diesel submarines, an a cruiser, frigate, and destroyer in exchange for the Pepsi. The company reluctantly accepted in order to continue bottling operations, and became the world’s sixth largest military power by number of submarines.

Pepsico only kept their navy for a few days, though. All the equipment was sold to a Swedish company for scrapping. But Kendall didn’t let National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft forget that Pepsico was disarming the Soviet Union faster than the United States.