Westinghouse Air Brake

Although many associate the Westinghouse name with appliances and electrical devices, the name first earned recognition in 1869 thanks to a revolutionary new railroad technology.

The Westinghouse Air Brake.

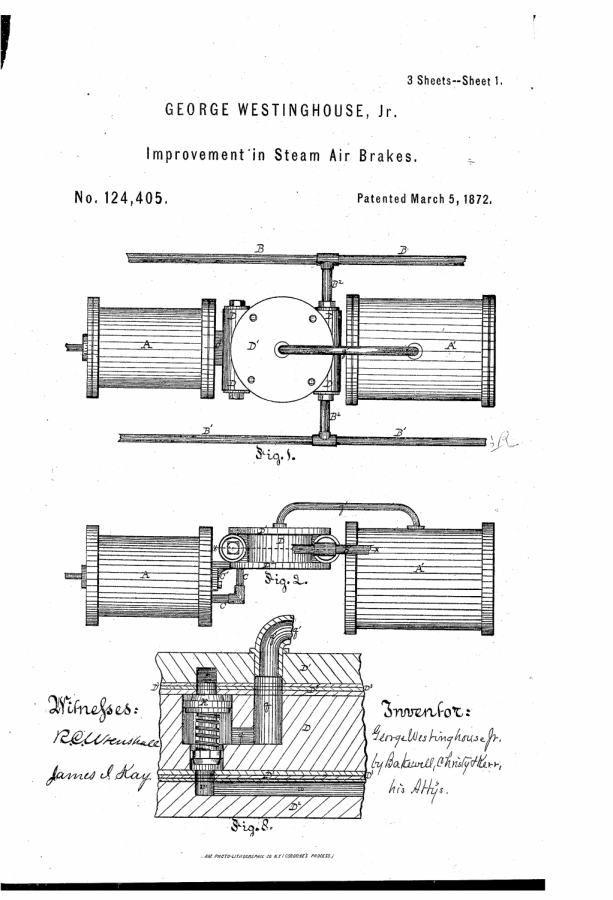

The revolutionary device can be seen in three diagrams and a description submitted to the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Titled “Improvement in steam air brakes” it is better known as Patent No. 124405A, issued to George Westinghouse in 1872.

And the papers conceal the importance of the new invention. Who would expect, after all, that a small stack of papers would save thousands of lives, billions of dollars of property, and help railroads run safer and more efficiently?

The Westinghouse Brake was a unique solution to a major problem. Stopping a train required brakemen to run across the tops of the rolling stock and manually apply the brakes by turning the brake wheel. That would apply the brake shoes to the wheels. Naturally, the brakemen had to be very strong. They also had to be able to listen to whistle and lights signals, and be aware of all the stuff crossing over the rails so as not to collide with it.

Stopping a train was by no means a precise science. Collisions were frequent, as were the deaths of brakemen. The first Westinghouse brake, the straight brake, changed all that. It worked by releasing air from a chamber on the locomotive through the air lines in each car of the train, using the air pressure to apply the brakes.

One problem with the brake was that the brakes were applied from the front of the train to the back. Therefore, during a quick stop the cars directly behind the locomotives would have the brakes fully applied before the cars at the rear had any pressure. This led to damage resulting from cars bumping into the ones ahead. However, the biggest problem is that the brakes were not automatic.

With the straight brake, adding air pressure was used to apply the brakes. If there was ever a puncture in the brake line or a disconnected coupling, all the air would rush out of the system, leaving the train without brakes. The system was improved in 1872 with the invention of the automatic brake. With the automatic brake, air pressure was used to release the brakes. If the air pressure was released, the brakes would apply.

In this manner, the new Westinghouse brake, the plain automatic air brake, was a safer way to run a train, as a release of air pressure would cause the train brakes to apply, instead of release. Now coupling mistakes or line punctures would prevent the train from moving, instead of the train getting underway only for the engineer to realise that he had no ability to stop the train.

The problem of the brakes applying from front to back still remained, however. George Westinghouse decided to address this problem with another iteration of the air brake. The quick action triple valve brake allowed air in the system to be drained uniformly throughout the length of the train, applying the brakes at the same time.

The brake worked by venting pressure on each car almost instantaneously, using a faster-moving triple valve. The triple valve opens and closes the inlet from the brake cylinder, while doing the opposite to the inlet from the auxiliary reservoir from the train’s brake lines. Each car was also equipped with an air cylinder, allowing the brakes to be released and applied at the same time as the rest of the train.

The Westinghouse brake first went into service on the Pennsylvania Railroad, as the brake systems were produced 12 miles outside of Pittsburgh in Wilmerding, Pennsylvania after 1889. The brakes soon spread to other railroads, and were later adapted to other modes of transportation, including trucks, busses, and amusement park rides.

The Westinghouse Air Brake Company no longer exists, but it is survived by two direct successors. Wabtec remains in Pennsylvania, manufacturing air brake system. The other, WABCO, is headquartered in Belgium and makes control systems for commercial vehicles.