Suicide is not a funny anecdote

In September of my freshman year, while talking to a friend who had just lost someone to suicide, I made the first suicide joke that I was conscious of. “I think I would kill myself if that happened,” I told her. Seconds later, my heart dropped to the floor as she looked at me with discomfort and hurt in her eyes. “I’m sorry, that was insensitive,” I quickly responded.

That was the moment in which I consciously made an effort to stop joking about suicide. It was the first time that I became aware that my words could hurt someone without my knowing it. I worked hard in the months that followed to replace texts of, “ugh kms [kill myself],” with messages reading, “ugh, so annoying.”

Nine months later, when I lost a friend to suicide, my tolerance for suicide jokes dropped away. It no longer felt like a joke, but a personal attack. It didn’t make sense to me. How could suicide be a laughing matter to someone when to me, it was the force that had ripped my heart into a billion pieces?

Suicide jokes were absent from my life for a long time; the only people that I spent my time around were people that had been affected by loss just as I had. Towards the end of my sophomore year and over the summer that followed, however, I began to notice the jokes again as I started spending my time with new people.

Hearing them made my heart skip a beat. I was shocked to realize that people actually still said things like, “okay, I’m going to kill myself now.” However, I was always so viciously uncomfortable in those situations that I refused to speak up; I figured that if I didn’t respond, people would get the message and stop joking. I soon found that that wasn’t effective, yet I continued to silently tolerate the jokes. Still, a question gnawed at the back of my mind: What if one of those was serious?

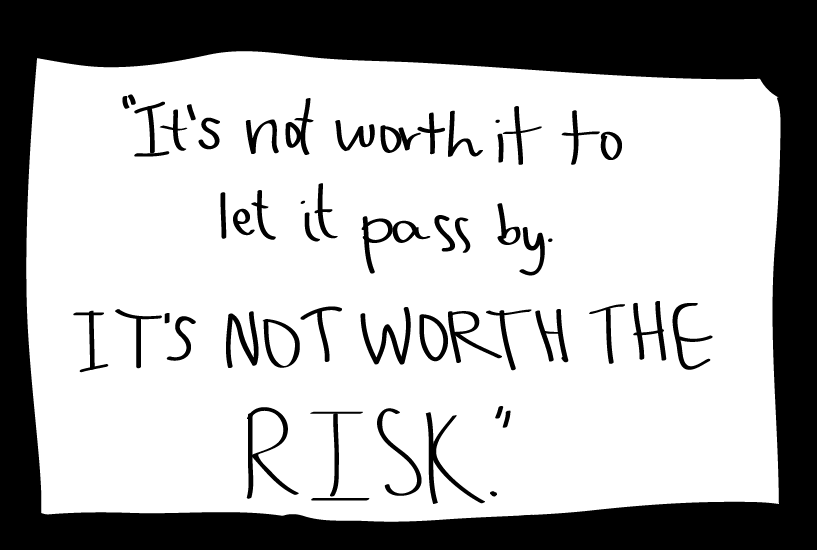

“Suicide jokes make my job as a peer educator really hard,” said Andrea Schnell, a senior entering her second year of Depression Awareness Group at CHS. “I’ve been trained to immediately respond and contact someone if I see something that resembles anyone [threatening] to harm themselves. It’s not worth it to let it pass by and [assume] that it’s a joke. It’s not worth the risk.”

After receiving extensive training from Robbie Stapleton, the teacher advisor of Depression Awareness Group (DAG) at CHS, and at a conference held at Pioneer High School, Schnell has consciously worked harder to prevent suicide jokes from being present in everyday dialogue at CHS. Though it’s proven hard for her, she continues to work hard to educate and bring awareness to mental illness and suicide.

“[The jokes] have been so normalized, which I find just awful,” Schnell said. “It belittles the experiences of others who have dealt with thoughts of suicide; people who are depressed or having thoughts of suicide work so hard to get out of that negative pattern, and it just feels mean to destroy all of their work [by turning it into a joke]. And it’s also really insensitive to people who have lost others to suicide.”

Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States and the second leading cause of death in Michigan for people aged 15-34, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). There are an average of 123 suicides every day in the USA.

For every death by suicide, there are 25 attempts, many of which go unnoticed due to underreporting caused by stigma surrounding suicide (according to the AFSP).

When we make suicide jokes, we subconsciously take away from the legitimacy of suicide or suicide attempts. Suicide is a pressing issue in today’s society, with a rate of 13.15 per 100,000 people between 15 and 24 (AFSP). It is often linked to depression and is a result of extreme mental pain and despair (according to Project Semicolon). It is not an anecdote in conversations about being bummed out or getting a bad grade.

“[Jokes] hurt the cause so much; it normalizes the experience,” Schnell said. “It makes it seem small, when [in reality] dealing with thoughts of suicide or dealing with having lost someone is really, really difficult, and people need to know that it’s okay to have a hard time and it’s okay to have these thoughts.”

Though I argue for the complete eradication of suicide jokes, I am always aware of the heavy stigma that suicide carries. Healthy, educational conversations about suicide should be normal in our lives. By talking about suicide in a serious manner, we have the opportunity to eliminate stigma and spread awareness, thereby helping the worldwide prevention efforts.

When considering making a suicide joke, observe your surroundings: Who is listening, and how might they be impacted day to day by mental illness, suicidal thoughts, or the loss of someone to suicide? Do your words negatively impact the suicide stigma? How could you rephrase your sentence? My hope is that after considering these factors, you could change your choice of words.

If you hear suicide jokes, don’t be afraid to call them out. You have the power to change the world and our society’s view of mental health issues. Stand up for this cause — not everyone is able to.

And lastly, because September is National Suicide Prevention and Awareness Month, I advise you to check in with yourself and with the people you care about. If you need help, don’t be afraid to ask for it. If you are struggling, know that you are not alone. You are supposed to be here, and there are people that want you here.

If you experience suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.