Escaping the vortex of perfectionism

A film viewing and panel discussion of “The Race to Nowhere” evokes hopes for change in our education system.

The screen flicked on, and immediately the heartfelt anecdotes began. High school, middle school, and even elementary school students of all ages and backgrounds shared their personal struggles with academic life. “So much pressure that I would wake up and feel… like I’m dreading it,” One high schooler said to the camera. On Oct. 11, the Ann Arbor District Library held a viewing of the film “The Race to Nowhere,” with a panel discussion directly following. The event was a partnership with the University of Michigan Community Scholars Program. The film’s aim was to shed light on the major flaws of our country’s culture around education. It centered around many high school students feeling extreme pressure to excel in the academic world and illustrated the struggle of meeting expectations catered to the very top percentile of learners. “The Race to Nowhere” interviewed and showcased the lives of students, parents, and teachers living in an environment focused around constantly developing, advancing, and expanding the definition of success.

Watching the film, I found myself thinking: any one of these students could be a Community High School student. The students interviewed in the documentary seemed to be facing the same struggles we often witness firsthand as Ann Arbor’s high school students. The ever-growing compilation of extracurriculars, volunteering, clubs, extra credit and AP classes, paired with overwhelming amounts of schoolwork and projects all geared towards the college application, weave together a scene that we in the learning community know all too well. Even more concerning are the mental, emotional and physical tolls taken on students’ health. Walk into any high school, in Ann Arbor or elsewhere, and ask the first student you see about how school work impacts their life. Their answer will most likely be a medley of sleep deprivation and extremely elevated stress levels, among the many other negative effects of a pressure-filled lifestyle.

The film was undoubtedly very relevant to our community. It also dove into the pressing question: what are all of these sacrifices for? It suggested that while our current education system does a great job at motivating students to get into the “best” colleges, it does not adequately provide them with the skills they need to thrive in these colleges. According to the documentary, the University of California — a notoriously difficult school to get into — had to remediate about 50% of the students they accepted. This serves as proof that a well-crafted application followed by an acceptance letter is not always a perfect representation of a student’s readiness for college. Although the students that applied for the University of California often had grade point averages greater than a 4.0, they ended up having to retake basic high school classes because they hadn’t been retaining the same information they had been getting A’s on.

This statistic highlighted another of the education system’s biggest shortcomings: while AP classes and advanced courses provide heaping amounts of content, oftentimes the content is not given enough class time, discussion, or review and is instead rushed through at breakneck speed. This often results in what the film called “mile-wide, inch-deep” coverage of important concepts. This method of teaching tends to prepare students for the college application, not for the college experience. Unrealistic expectations have also lead to an epidemic of cheating and plagiarism as students are taught to prioritize their grades over their comprehension of the material, and even over their moral compass. A study done for the movie found that less than 3% of the 5000 students studied had never cheated or plagiarized. The piece also argued that high school and college should be times to learn about oneself; to find happiness and to strive for excellence in whatever it is the student wants to pursue. With the rigid, quantity over quality oriented environment of high school, students are often not given the time, resources, or mentality they need to make crucial progress in their development as scholars and as people.

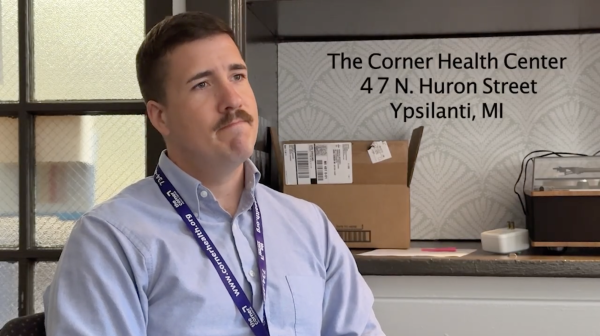

On the panel were John Boshoven, alum of Community High School: Counselor, Emeritus, and Co-Chair of the Ann Arbor Public Schools counseling department; Patricia Manley, a Trustee on the Board of Education for Ann Arbor Public Schools; and Todd Sevig, Director of the Counseling and Psychological Services at the University of Michigan. As the movie drew to a close, each panel member shared their opinions on the movie.

“Everybody knows it’s unrealistic,” Sevig said. “But somehow some students have internalized that [they] have to be nearly perfect throughout the day, and the week, and the semester, and the year.” Sevig expressed his hopes for positive change in our school system, sharing one of his favorite parts of working in education: seeing changes and growth in students.

“We see when students get better when they can navigate it and not get sucked up into the vortex of perfectionism,” Sevig said.

After all three panel members had had a chance to speak, the room became a center for discussion. Students, parents, administrators, teachers, and others for whom the movie had depicted a painful reality were encouraged to share their points of view.

One woman was concerned about her two kids, both freshmen in the Ann Arbor Public High Schools. The amount of homework they were getting, she worried, was just too much. While she knew that both wanted to go to the University of Michigan, she didn’t want them to put too much pressure on themselves. She offered the idea of creating more schools like Community, smaller schools with smaller classes for a more tight-knit and specialized learning environment. Boshoven responded that with the development of Ann Arbor’s third comprehensive high school, Skyline, there had initially been discussion of creating two or three other community-style schools rather than one large public one. However, there was a push from many parents for more sports, orchestra, band, and other programs that are harbored and strengthened by larger schools.

Another parent worried about her elementary schooler, who she noticed was facing anxiety over classwork and homework and being punished with loss of recess time. She wanted to make sure that Ann Arbor Public Schools would allow children time to play and develop important social and imaginative skills, without it being conditional in relation to how much work the child finished.

A student at the University of Michigan shared an alternative method of grading that was used in her Italian class in high school, and one that she thought was healthier for the students and more indicative of their understanding of the material. An Ann Arbor Public Schools teacher attested to giving either credit or no credit for her class, in an attempt to relieve some of the stress her students were facing. She was received with applause and cheering from the crowd, which was full of college and high school students, some of them her own.

As a wide variety of students, parents, teachers, and counselors came forward, the stories sounded more and more similar. All of them wanted happiness for their students, their children and themselves. They wanted education to be a process that created a sense of joy, motivation, and self-expression for students, rather than anxiety, stress, and toxic perfectionism. There was discussion of having homework-free weekends or even introducing alternative methods of grading for some classes. Monitoring time spent on schoolwork outside of school was also a priority, in addition to opening the conversation on mental health and creating a more supportive environment for students experiencing stress, anxiety, and depression. The hope was that as a community, we can shift our thinking when it comes to our public schools. We can change our goals from students having 4.0 grade averages and perfect test scores to goals that will benefit students not only as students but as people. We can change the ideal of students being perfect to the ideal of students having a sense of self and love for what they are learning. Most importantly, we can change our education system for all students to have a happier, healthier relationship with their school.

Lacey Cooper is a junior at Community High School and a Copy Editor on the Communicator. Entering her third year on staff, she is ecstatic to be a part of this community of student journalists. Lacey enjoys singing, reading, writing, watching The Office, and goofing off with friends. On a weeknight she can be found at rehearsal, the library, or a friend’s house (although mostly at rehearsal).