High schoolers in the lab

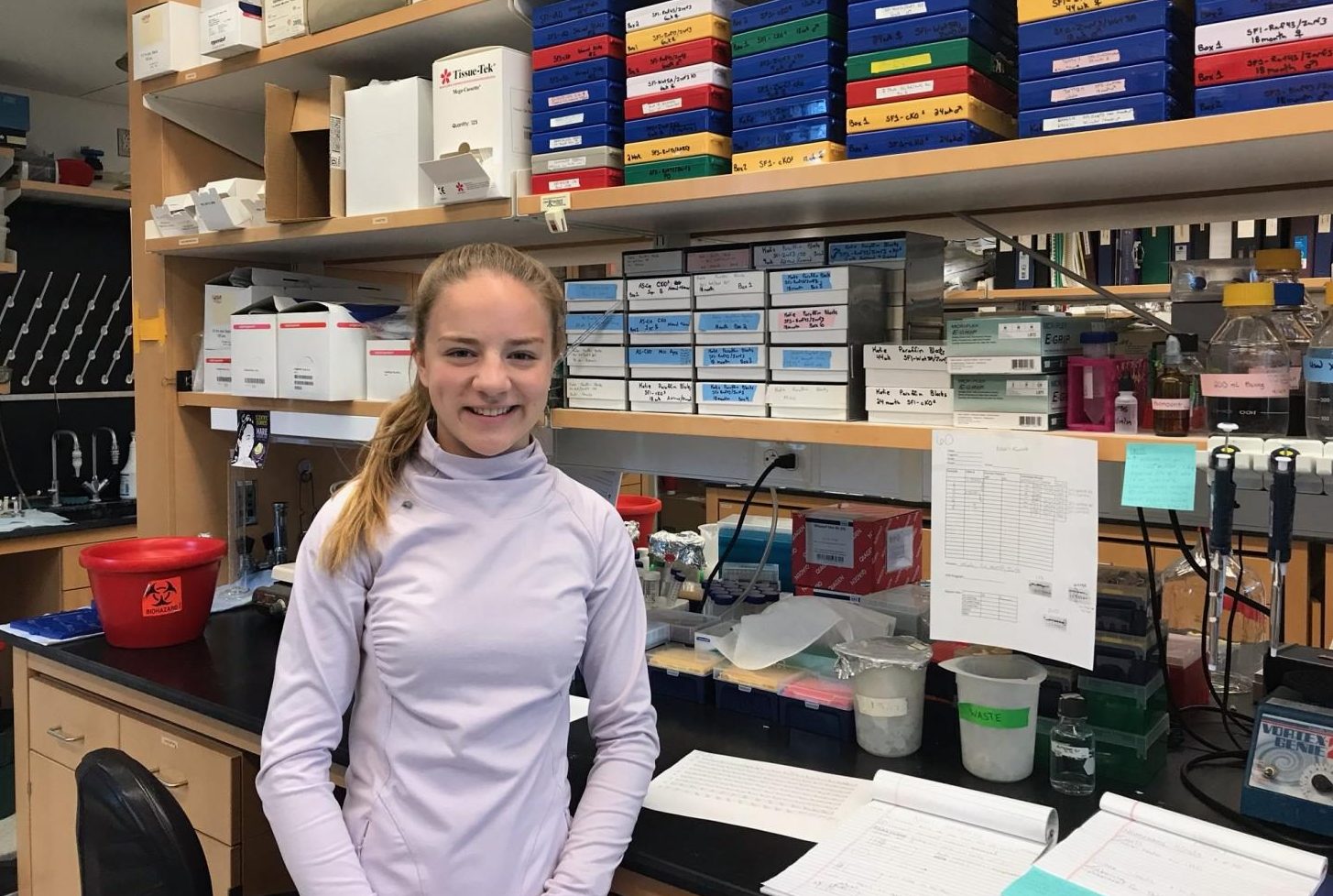

Ammer in the Hammer lab. “The work that I’m doing is to learn more about adrenal biology specifically and what happens in the adrenal with cancer,” Ammer said. “Once we know more about that, then we can better focus treatments.”

One morning, in the spring of her sophomore year, senior Julia Ammer stepped into the University of Michigan’s Hammer Laboratory on a field trip organized by Marcy McCormick. There, the group dissected a mouse and ran gel electrophoresis, a process that lines up DNA according to size. Ammer’s interest in cancer biology and conducting research spurred her to follow up with the lab.

At the time, she had little prior knowledge of adrenal cancers, the focus of the Hammer lab’s research. While cancers of the adrenals — small glands that sit on top of the kidneys and create a variety of hormones — are particularly deadly, their rarity means the field of research is relatively new.

“I’ve had a lot of family members affected by cancer, but I also have always been interested in the human body,” Ammer said. “After taking Biology 172 at University of Michigan, I became more interested in the cellular mechanisms, so zooming into the human body on a smaller scale. I think for me, what makes it so interesting is that it is all happening in human bodies.”

Ammer found cancer to be a particularly interesting example of when biological mechanisms go awry. She also stresses the importance of cancer from a public health standpoint; one in three women and one in two men in the U.S. will be affected by some form of cancer in their lives.

After doing a CR class with a Hammer Lab graduate student during the fall of her junior year, she reached out to Dr. Gary Hammer, who leads the Hammer Lab, once more. Even with the connection she gained from the class, Ammer still expected that getting a position would be difficult.

“[High schoolers] really are at the bottom of the food chain,” Ammer said.

Despite this, one of the postdocs offered to mentor Ammer, starting the following summer. While the CR was more about the basics of adrenal gland development, this internship would give her more hands-on experience.

During that summer of 2018, she dedicated 16 hours each week to the lab. Now, during the school year, she spends around six to ten hours per week.

In the lab, Ammer’s main role is assisting her mentor through genotyping and staining. In genotyping, the process of determining differences in genes, she finds if specific genes have been “knocked out” — or are no longer present — in lab mice. After this, her mentor is able to examine the results of mice having or not having these specific genes. In particular, her mentor is interested in the ZNRF3 gene, because mutations in this gene are frequently found in human adrenal cancers.

Staining uses special dyes to boost contrast, making the components of a cell easier to see. Thus, researchers can more easily see what is happening inside the adrenal gland. Such stainings provide the evidence to support one of the lab’s hypotheses — that adrenal tumors go through a transition stage — by marking specific proteins that show the transition occurring.

Ammer also designs experiments at the desk and taking and examining images. These tasks can become quite repetitive. However, she realizes that the work is all worthwhile; what she does contributes to something greater — better outcomes for patients.

“Instead of just treating one patient like a doctor does, we’re working to develop treatments for hundreds and hundreds and even thousands of patients,” Ammer said. “To know that you are making a large impact on people that are affected with cancer is really, really special.”

In her time at the lab, she learned at depth about science and adrenal biology but also about the research process as a whole. The experience has exposed her to a greater understanding of daily life in the lab and the profession. While doing research as a high schooler may seem difficult, it is certainly doable.

“It’s really just going to take persistence and finding the right people to work with and finding the right mentor,” Ammer said. “If the first person you reach out to or the first lab or professor doesn’t say yes, that’s okay. You’re lucky, especially in Ann Arbor, to live in a research-abundant place. I would really recommend reaching out to as many people as you can, and eventually somebody will say yes.”