The fraud of conversion therapy

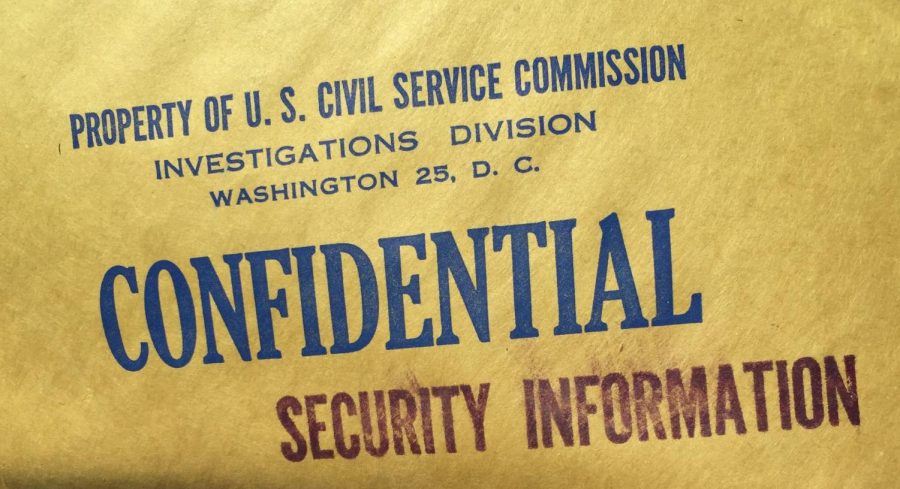

Photo courtesy of Lisa Linsky. This is an example of many of the documents found and reviewed for the research conducted by the Mattachine Society. Visit the White Paper here: http://bit.ly/themythofconversiontherapy

February 17, 2020

It all started in 2012 when Patrick Salmon and Charles Francis visited the law firm McDermott Will and Emery’s pride program to share Salmon’s film Codebreaker — a documentary about a queer mathematician. After the screening, Francis approached Lisa Linsky, the firm’s first partner in charge of LGBT Diversity and Inclusion. Francis is the president of the Mattachine Society, which was one of the first LGBTQIA+ advocacy groups, created in 1961. The group was founded by a former government worker after he, like many other queer people, was fired from federal employment after he was discovered to be gay. The Mattachine Society served the LGBTQIA+ community for many years, supporting the establishment and preservation of queer rights. Francis reinvigorated the Mattachine Society with a new mission: documenting and preserving LGBTQIA+ history.

The advanced diversity program at McDermott, one that Linsky spearheaded, grabbed Francis’ attention. That’s why, after the documentary screening, he approached her with a proposal: The Mattachine Society and McDermott lawyers could work together to get access to confidential government records about queer history.

The Mattachine Society has partnered with McDermott for eight years now, with 20 lawyers participating. One of their biggest projects began in 2017 when Pate Felts, the Vice President of the Mattachine Society, was in a library in Little Rock Arkansas and something caught his eye — an article about a man named Garrard Conley, a man who’d escaped from a conversion therapy program and his experiences there.

On his way home, Felts was looking for reading material at a Hudson News in the airport when he stumbled upon a book called Boy Erased. It was written by the man in the article, Conley. Felts bought the book and read it on the plane ride home.

“By the time he landed,” Linsky said, “Pate was emailing me and Charles to say ‘I’ve just read the most phenomenal book; I think we should try to get the author to meet with us and see how we can do a project together.’”

They managed to get in contact with Conley and met with him in Washington D.C. to discuss what he’d experienced at Love in Action, the conversion therapy program he went through. In talking with Conley, it was discovered that he left Love in Action with workbooks they had provided during his time there. This was against the program’s policy, but Conley had escaped with them because his mother picked him up and quickly removed him from Love in Action.

Conley got in touch with John Smid, the reverend who used to run Love in Action. For 25 years, Smid was a figurehead for “ex-gay movement,” or the group of individuals who had been converted to heterosexuality. Now, Smid has left the program and is married to his husband Larry.

“John Smid came out and said ‘What we did in conversion therapy, in Love in Action, was wrong,’” Linsky said. “‘It didn’t work. It was a fraud and it was horrible — young people killed themselves.’”

Smid and Conley both donated papers and memorabilia from Love in Action to the Mattachine Society; the documents have since been moved to the Smithsonian.

After learning about Love in Action, the Mattachine Society and McDermott lawyers decided to take up projects that would help society work towards ending conversion therapy. To do so, they first had to research the beginnings of discrimination towards LGBTQIA+ people — to tackle its most modern forms, they needed to understand conversion therapy’s genesis.

Sexual orientation change efforts (SOCEs), they discovered, began in the mid 1800s. At that time, homosexuality was classified as not only abormal, but an illness, despite scientific research concluding that queerness was a “normal permutation.” It was believed that same-sex attraction was an effect of genetic defects, poor parenting and sexual abuse.

Early SOCEs attempted to reverse queerness by “enforcing heterosexual behavior”: suggesting sex with prostitutes of the opposite gender; promoting opposite-sex marriage; and some called for orgasmic reconditioning, which was masturbating to pictures or video of the same sex, then, immediately preceding orgasm, switching to pictures or video of the opposite sex. In addition to promoting attraction to the opposite sex, many SOCEs also promoted forms of torment.

Conversion therapy was so common in the 19th century, the Farral Instrument Company marketed a line of tools to aid medical conversion treatments. They sold the Acoustic Keyer, which would shock patients when they were aroused during recounting homosexual acts; the Personal Shocker to help patients prevent relapse; and the Office Shocker, which was meant to be used in a doctor’s office. Farrall products were also used to treat “child molesters, transvestites, exhibitionists, and alcoholics.”

Not only were early forms of conversion therapy prevelant among medical professionals, but, during the Cold War, the federal government created a hospital for SOCEs — St. Elizabeths in Washington D.C..

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the United States was undergoing what historians would label a “red scare,” or fear of the rise of communism within the country. At the time, as the U.S. was competing against the then-communist Soviet Union in a nuclear arms race, the government was purging communist or presumed communist staff members from federal employment.

It was believed that LGBTQIA+ people were national threats, as they would supposedly be easily blackmailed.

“The idea was that given widespread and popular disgust with homosexuality, [foreign] agents could leverage gays to betray their country in wartime,” said Douglas Charles, author of Hoover’s War on Gays: Exposing the FBI’s “Sex Deviates” Program.

In 1953, J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), sanctioned queer identity as “a behavior threatening national security.” Hoover then instituted his sex deviates program, a campaign to educate the American people about the dangers of LGBTQIA+ people, claiming they would kidnap or otherwise abuse children. For nearly 50 years Hoover would continue to persecute using his power in the FBI.

Many federal employees who were discovered to be queer would be sent to St. Elizabeths — the aforementioned governmentally-sanctioned conversion therapy — to try to ‘overcome’ their sexual orientation and to be persuaded to reveal the identities of LGBTQIA+ coworkers.

“While the government was ferreting out homosexuals from federal employment, it was also trying to turn these now former gay employees against their colleagues; they would try to make them turn informants,” Linsky said.

In trying to change the sexual orientation of staff, the government employed various forms of abuse.

“These people underwent significant torture,” Linsky said. “Torture. It really was — it was torture: electroshock therapy; insulin therapy; they would put them in comas for weeks at a time, and then the FBI and other government officials would show up and interrogate them. They would get them to tell them the names of others who were gay so the government could go after them and get them out of federal employment too. So it really was a huge government effort to purge LGBT people from federal employment.”

With all of this research, the Mattachine Society and lawyers at McDermott created a white paper — a report giving information and proposals on an issue. The purpose of this paper was not only to summarize the history of SOCEs in the United States, but to educate the American public on modern conversion therapy.

Conversion therapy is still flourishing in the United States. According to Linsky, many of these practices are faith-based, as they are often above the law due to religious exemptions. Currently, conversion therapy is legal in 31 American states and 53% of the LGBT population in the U.S. lives in areas where conversion therapy is not banned. Conversion therapy is not outlawed in Ann Arbor.

“Many people, and perhaps most Americans are in disbelief when we talk to them about conversion therapy,” Linsky said. People typically have a knee-jerk reaction that goes like this: ‘Wait, that doesn’t go on anymore,’ or ‘That’s illegal; you can’t do that,’ or ‘That’s something that happened back in the ‘50s or the ‘60s, right?’ People are somewhat incredulous that there are still ministries and camps and mental health professionals who are trying to convert young people.

“What we have tried to do through our work with the Mattachine society is get out there,” Linsky continued, “get the paper out there and educate, educate, educate: educate teachers, educate parents, educate communities about the importance of understanding that this ‘therapy,’ whatever form it takes, it doesn’t work.”

Smid, for nearly 30 years, lived as a poster-child for the ex-gay movement; he lectured all over the world, wrote papers, created a curriculum for conversion therapy and ran Love in Action.

But, Linsky said “it was all made up,”

Conversion therapy didn’t work for Smid: He was never successfully converted to a heterosexual lifestyle and left Love in Action to marry the love of his life — another man.

“Young people are being hurt,” Linsky said. “And they’re being hurt in ways that are long-lasting. We don’t want to see that happen, we don’t want to see another young person try to hurt themselves. The more we can get out there and talk about this and educate the public that you are who you are and you can try to deny who you are, but you’re not going to be living an authentic life and there’s no one that can change you.

“Conversion therapy is harmful and it doesn’t work. It really is a big old fraud.”