The lottery process: How does it really work?

February 24, 2020

CHS counselor Brian Williams reached into a black trash can and pulled out an index card as a group of teachers, staff, PTO parents and two auditors commenced the lottery for the new freshmen class come fall 2020.

The lottery wasn’t the first method used by CHS.

For many years, students would simply drop off an application form as a first-come, first-serve process. Students would have to line up outside of the school the day of registration. But eventually Community became more popular and the lines would form a day or two in advance.

When it became clear that having students drop applications off at Community wasn’t working they changed the location several times before beginning the double-blind lottery.

First, they tried to have application drop offs be at the Balas building — the AAPS headquarters — but this proved to be equally as problematic; parents began lining up a week before the deadline to turn in their applications.

Next, they tried keeping the application drop off area a secret until they would release it on the radio. Parents began to drive all around town hoping they’d be close by the time it was announced.

“People drove like idiots,” said Liz Stern, CHS science teacher. “They broke all sorts of laws to try and get to that spot. That obviously didn’t work.”

The lottery has been around for over 20 years, and throughout those years, flaws have been discovered and fixed. CHS dean Marci Tuzinsky told the room that there is an eight page list of improvements and steps they take to conduct the lottery.

Having been improved, students now enter their name by meeting two requirements: filling out an online application and attending one of many information sessions. Students also must either be an Ann Arbor resident or have already been attending AAPS as a school of choice student since 8th grade.

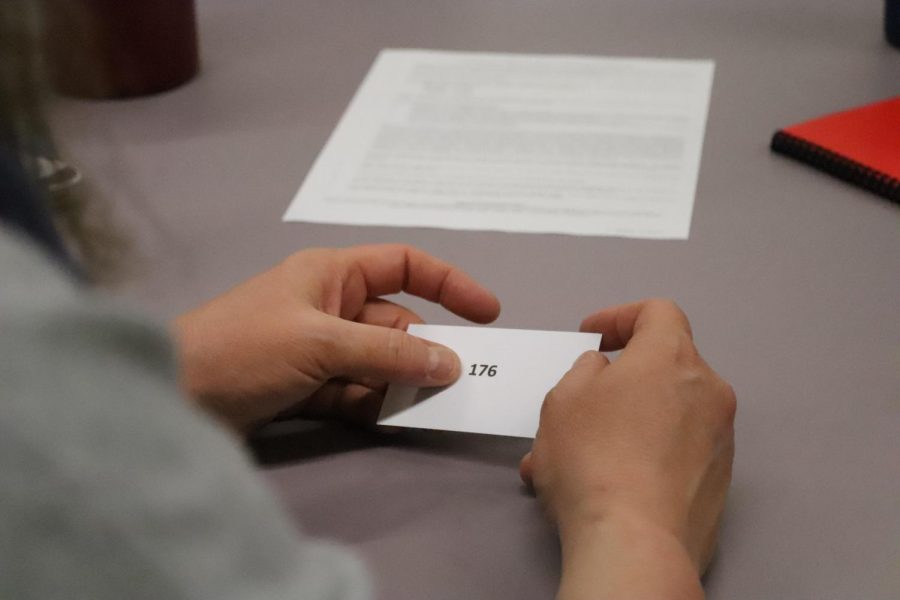

After all applications are in, students are assigned a temporary number that they will use to find out if they got into Community when the results are posted.

This year there were 340 eight graders who applied. Out of those 340, 132 got accepted. On top of that, any child of a CHS staff member is guaranteed a spot and not included in the lottery; in the past, no more than five staff children have attended within the same class. Lastly, the first two AAPS staff member children are brought to the top of the waitlist.

The drawing itself is double-blind, this means they randomly draw the student’s name and their number at the same time. Both names and numbers were shuffled, so the first name drawn wasn’t guaranteed a spot.

Before they began drawing cards, Tuzinsky established the process of the lottery to the two auditors. Auditors make sure that certain processes — like the lottery — are well-regulated and ethical.

To keep the process ethical, it’s done by hand, which makes it lengthy because they don’t allow a computer to do it — even though it could pair the names with numbers instantaneously.

“The two hours it takes us to do this saves us far more than the time it would take for everybody to question whether or not it was valid,” Tuzinsky said.

This year Brian Wiliams drew the names of the students, a job he has jokingly dubbed “not dream crushing,” while French teacher Danelle Mosher was given the “dream crushing” job of drawing numbers. Once Williams and Mosher pulled numbers they announced the name to the “scribes,” Jefferson Bilsborrow, Gretchen Eby, Craig Levin and Katy Sanderson. The scribes located the students name and Danelle then told them the number. They recorded the number and finally Tuzinsky took both cards and stapled them together to clear up any confusion that may appear in the future.

Tuzinsky and Sanderson were worried the amount of name cards wouldn’t match up with the amount of number cards. Once it was near the end, Mosher and Williams would report their amount of cards to the room. And with the last pair of cards drawn, the lottery ended with a student taking one of the winning spots.