In My Dreams

March 12, 2020

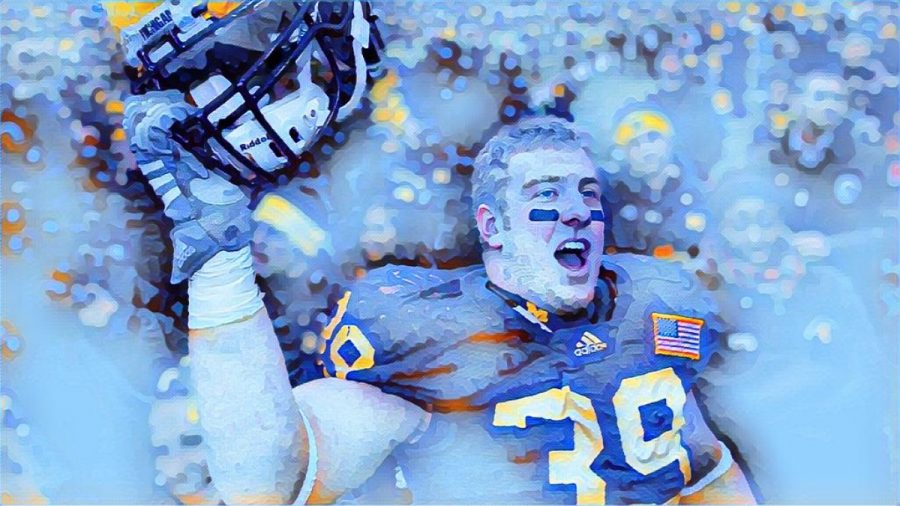

As a boy growing up in Ann Arbor, Will Heininger’s childhood dream was to play football at U of M under Lloyd Carr. Freshmen year was a dream come true. The summer following would not be. The summer between freshmen and sophomore year in college, Will Heininger’s life fell apart: his parents divorced, his dad moved to Chicago and his mom bought a new house that didn’t feel like home.

“It felt like I went from 100 to zero in a week,” Heininger said. He knew something was wrong when he constantly had racing thoughts and questions about life, but he hadn’t been taught how to express his emotions.

Growing up Heininger was not educated about mental health and no one talked about it, so when he went into a major depression he labeled himself as going crazy. He understood it as something hard that he would have to deal with alone. Heininger constantly had thoughts running through his head: “Coach would kick me off the team… my girlfriend will breakup with me… my friends weren’t going to like me.” He felt that he had to keep his mental illness to himself. Other athletes on his team were going through the same struggle as Heininger, however the silence kept them isolated in a tough sport.

It was at football practice where Heininger fell apart. When it happened, his trainer led him to Barb, a U of M therapist who saved Heininger’s life. Going into therapy, he didn’t believe he would ever get better. After starting two different medications and therapy and having both fail, he believed even more he could never get better.

His coach told him, “Will, you’re a good football player, but you’re good when you’re healthy, when you’re well, and right now it’s your job to get well.”

Heininger had always feared talking to his coach about his depression because he thought he would be seen as weak and not worthy of playing. However, after talking to his coach his entire mentality shifted, and Heininger wanted help. He started to direct his energy towards his well being and therapy. After working in therapy, he noticed the previously racing thoughts he had were coming less and less often.

“Once I learned to separate my wellbeing from my [football] performance was when both of them got better,” Heininger said. Sophomore year, Heininger returned to football; he was playing his best game ever. Heininger got his best grades ever. He was working in therapy and finding a medication that worked for him; out of therapy he was implementing the tools he learned in therapy in his everyday life.

“It felt like I had a cheat code going through college after that because the thoughts that would like throw me off, I could catch early and evaluate: Is this useful? Is this even true? And if it wasn’t, just be able to let it go,” Heininger said. Even once Heininger was well, he continued going to therapy, taking medication and using skills that he still practices today. Using the tools at Michigan, he thrived. Heininger started understanding people in a new way that helped him understand life better.

After Heininger graduated, he moved to Chicago and got a job in financing for two years. During that time his dad, 55 years old, had been rehospitalized and diagnosed with bipolar disease. Heininger’s father had told him the diagnosis explained things he had felt for decades and was the most important diagnosis of his life.

During this same time, Heininger had gotten a call from the Michigan Depression Center asking him to present an award for students who are involved and work with mental health. Heininger gave the award and shared his story for the first time publicly.

After he presented, he had a doctor from Phoenix approach him and ask him to go to Phoenix and present. “Nobody is talking about this as in mental health in sports. This needs to get out,” the doctor told Heininger. While working in finance in Chicago, Heininger took time off to present about mental health in sports in Phoenix.

When he got back to Chicago, the U of M Depression Center contacted him offering him a job working on a project with mental health in athletes. “That was when my career took a hard right hand turn and got into mental health,” Heininger said.

Since Heininger there have also been many other student athletes with mental illnesses. Kally Fayhee was a swim captain at U of M and had a dream to become an Olympic swimmer. She had trained for the Olympics and when it came time the only thing that stopped her was point-zero-one pounds over the weight restrictions. After not making the team, she was determined to achieve an Olympic swimmer’s weight. This turned into an eating disorder. When her team found out, many of them were also struggling with eating disorders.

Heininger recognized that mental illnesses cut across sports, and he thinks that changes are needed with coaching practices. Verbal abuse has been normalized in “tough” sports like football and that environment is dangerous for student athletes.

On February 13th Heininger and Stephanie Salazar visited Robbie Stapleton’s advanced health class from the U of M Depression Center. Heininger has traveled the country and talked to over 100,000 students. After presentations, some students individually talk to Heininger about mental health. “And each [student’s story] is a puzzle piece and fills in this puzzle to me, which is mental health,” Heininger said. One of the struggles with this job is knowing your impact with prevention since it isn’t visible — that goes for all of public health because it is prevention.

“If you don’t have any mental health education, you’re much more likely to do what I did and let something just eat at you and make you miserable,” Heininger said. Recently when Heininger was presenting in a middle school he asked the kids if they had heard of depression and anxiety before and all of their hands went up. As a followup he asked all the adults if they had learned about mental health before they were 18 and no hands went up. The middle schoolers reactions were confusion. One asked, so people have had this but just not done anything about it? Heininger’s response: Yes.

“The biological components of well being I think are less and less present in the current generation, and it’s not your fault. It’s just the world that you’re raised in,” Heininger said. He talks about human’s stress response system that is similar to the same system humans had many years ago to keep themselves alive in the wild. This stress system sends thoughts and questions through our heads throughout the day. Heininger is seeing Generation Z recognize their stress responses and understand how their brain works so they can get help and catch mental illnesses early. Another way that has become more popular to catch mental illnesses early are mental health screenings. It has been proven that with some mental illnesses, like depression, the brain physically changes and you can tell that in mental health screenings.

In early to mid 1900s, mental institutions had become more common in the United States. People with mental illnesses were sent to these institutions that resembled prisons because society portrayed them as dangerous to society. In these hospitals and institutions people died and were not treated for their illnesses because people didn’t know they were even treatable. This ideology created stigma around mental illnesses and options for getting help.

The U of M Depression Center centers their prevention work around three prongs: raising awareness, reducing stigma and promoting getting help. With the student athletes and anyone else, Heininger finds the most important thing a friend and society can do is just normalize mental illness and still be there and have empathy — just like you would for someone with a broken leg.

Heininger has been asked, “How could you have depression you play football for Michigan? You said that was your dream?” His response is, “And that’s exactly the question I would have asked because it’s how I thought about it before. I’ve learned that’s like asking, how could you have cancer you play football for Michigan?” Mental illness does not discriminate; Heininger did not choose to have depression. But he learned how to live with it.

National Suicide Prevention Line: 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741-741

U of M Psychiatric Emergency Services: 734-936-5900