Knives out analysis: An allegory for America

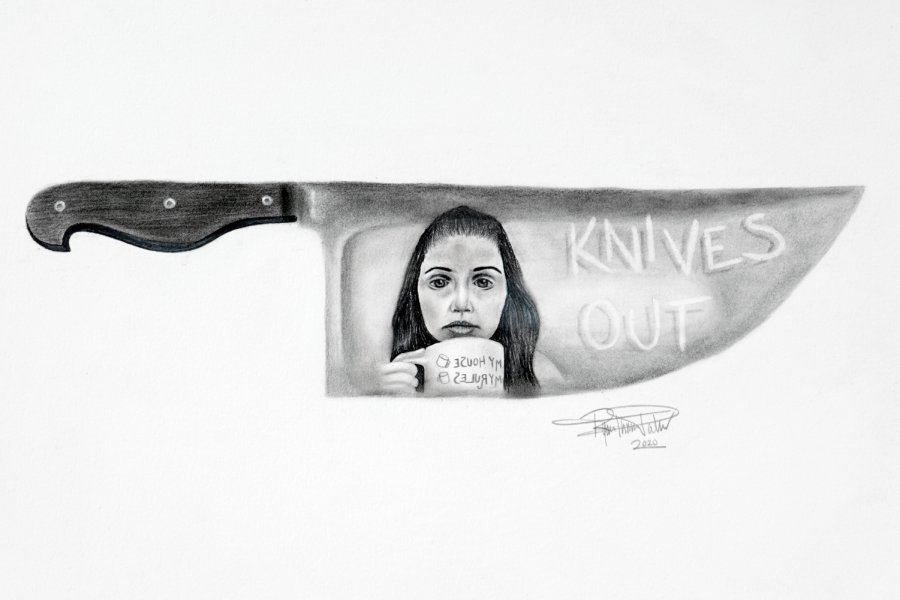

This art piece by Ryan Thomas-Palmer shows Marta, the protagonist, in the reflection of a knife, holding a mug that reads “My house, my rules, my coffee.”

April 14, 2020

*Spoiler warning*

“Knives Out” has all the elements of a typical murder mystery and a modern twist: the story is told through the eyes of an immigrant nurse, Marta Cabrera, who plays by her own rules. She tells the story in the way that makes the audience question America’s political state and the way they live their lives.

Harlan Thrombey — the rich, white man who controlled most of the Thrombey wealth — was found dead the morning after his 85th birthday party, which was attended by his two children as well as several other members of the family. Private detective Benoit Blanc believed Harlan was murdered, in spite of local law enforcements’ assurances that he killed himself.

It is revealed early on that Marta, Harlan’s nurse, accidentally switched his two medications after their nightly game of Go, administering a fatal dose of morphine. After Harlan discovered he had only minutes left to live, he persuaded Marta to leave and suggested she only give the police pieces of the truth, as she involuntarily vomited whenever she lied. Given that Marta’s mother was an undocumented immigrant, Harlan and Marta worked together to frame Harlan’s death as a suicide to protect Marta and her family.

Everything seemed to be going according to plan. But, the reading of Harlan’s will revealed that none of the Thrombeys would receive any of the inheritance; instead, Harlan’s wealth and assets would be given to Marta. The Thrombeys became incredibly suspicious of Marta and attempted to convince her to give up the estate she had inherited.

By the end of the film, Blanc discovered that Ransom, one of Harlan’s grandsons, switched the medicines before Marta administered them. Ransom knew that Marta was the sole beneficiary of Harlan’s riches, and he wanted to hold her accountable for Harlan’s death in order to contest the will. To cover his tracks, Ransom killed Fran, the housekeeper, then was arrested after giving a confession.

Throughout the film, there is a dramatic contrast between the dispositions of Marta and the Thrombeys.

Even when it hurt her, Marta stuck up for others. When she found Fran dying, she called the police, despite the fact that she believed Fran knew she was guilty. After coming clean to Blanc, Marta wanted to be the one to tell the Thombeys about Harlan. The fact that she cannot tell a lie is the greatest testament not only to her truthfulness, but her kindness; as a result, the audience is inclined to sympathize with her.

The most striking of Marta’s attributes, however, is her outlook on life.

During their nightly game of Go — a game played with white stones and black stones in which the objective is to create a sequential line of game pieces — Marta took the black stones. Harlan, who always lost to Marta, asked her why he could never beat her.

“Because I’m not playing to beat you,” Marta said. “I’m playing to build a beautiful pattern.”

This scene perfectly embodies Marta’s philosophy, which is also a recurring theme throughout the film: it is not as worthwhile to beat someone at their game as it is to play your own.

Marta is wonderfully juxtaposed by the Thrombeys, many of whom act selfishly throughout the film.

The Thrombeys were polite to Marta on the surface, often calling her part of the family. However, she was not invited to attend the funeral, despite the claims of many Thrombeys that they were “outvoted” when advocating for her to attend. None of the Thrombeys even seemed to care about Marta enough to know where she is from; she is referred to as being from Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay and Brazil.

Even through a veil of charm, it is clear that the Thrombeys always saw Marta as inferior when many of them treated her like “the help”: some of them handed her dishes to clear at Harlan’s party; and she was obliged to refer to Ransom as Hugh — only those who he saw as equals were allowed to refer to him by Ransom, his middle name.

As a white family, the Thrombeys were able to benefit from the accomplishments of nonwhite people; in the scene that introduces Richard Drysdale, Harlan’s son-in-law, he raves over the musical Hamilton, quoting “Immigrants, we get the job done.” These moments in “Knives Out,” are strikingly similar to scenes in Jordan Peele’s thriller “Get Out.” In that film, the African American protagonist’s white parents-in-law try to prove to him that they are not racist by saying things like “I would have voted for Obama for a third term,” and sharing a story about how much they loved Jesse Owens; however, by the end, it is revealed that the family is savagely mistreating black people.

The way that the Thrombeys benefit from the culture of nonwhite people is similar to their relationship with Marta: they love her on the surface, but do not actually care for her when she needs them.

Marta is only considered a part of the family when it is convenient.

It became incredibly inconvenient, however, when the Thrombeys discovered that none of them were in Harlan’s will.

After this was uncovered, the Thrombeys quickly turned on Marta, accusing her of sleeping with Harlan, calling her a “dirty anchor baby,” claiming that she was manipulating him, trying to prove that she “had her hooks in him,” and eventually following her out of the house to yell at and harass her.

They would not believe that she earned her place in Harlan’s will.

The Thrombeys, many of whom were business-owners, considered themselves to be self-starters who worked their way into wealth from the ground up. They had a lot of pride. But most of their success actually came from Harlan, who loaned them money or otherwise assisted them in their businesses.

Marta, however, truly got where she was on her own. By becoming one of Harlan’s only true friends and confidants, Marta showed him that she was trustworthy. In fact, Harlan seemed to respect her more than his own children; he would often talk to Marta about his issues with his family’s greed and immature dependency on his money. Marta empathized with Harlan and proved to him that she was worthy of his inheritance. And when she got that inheritance, she became the black stones in their Go game, interrupting the chain of white stones just like she interrupted the chain of white Thrombeys benefiting from Harlan’s wealth.

Many of the main points in “Knives Out” are made during allegories like that game of Go.

During Harlan’s party, for example, Richard beckoned Marta towards the couch, where he was seated with a few family members while they discussed politics. Many of the Thrombeys are afraid of immigrants, and said things like “We’re losing our way of life and our culture,” “America is for americans,” and, most strikingly, “We let them in and they think they own what’s ours.”

This phrase is shockingly similar to the reaction of the Thrombeys when they discovered that Marta was the sole beneficiary of Harlan’s will, which is where their judgement is flawed: the inheritance was not theirs, as they assumed it was — it was Harlan’s to give to whom he felt deserved it, and he chose Marta.

One night, Marta walked into her home and sat on the couch with her mother. Her mother was watching a murder mystery movie with Spanish audio. It was a murder mystery, only through the eyes of an immigrant.

“Knives Out” is a murder mystery through the eyes of Marta, the kind nurse who plays by her own rules and ends up the sole owner of a large estate as a result. Not only is the story an allegory for America — it is a guidebook for how we must live our own lives.

The film ends with a powerful image: Marta, standing on the balcony of the Thrombey estate, looking over the rest of the Thrombeys as they gaze at her from the ground, speechless. She is holding Harlan’s mug, which reads “My house, my rules, my coffee.” As she sips that coffee, she humbly surveys all of the prosperity she is clearly shocked to have inherited, but that she even more clearly deserves.

Marta’s story is a call to action. It urges us to emit as much kindness into the world as we can, instead of comparing ourselves to others, and trying to beat those who oppose us. It urges us to build a beautiful life.