Glenn Greenwald, The Intercept and Truth

What we can learn from a petty, insular squabble between people ostensibly on the same team

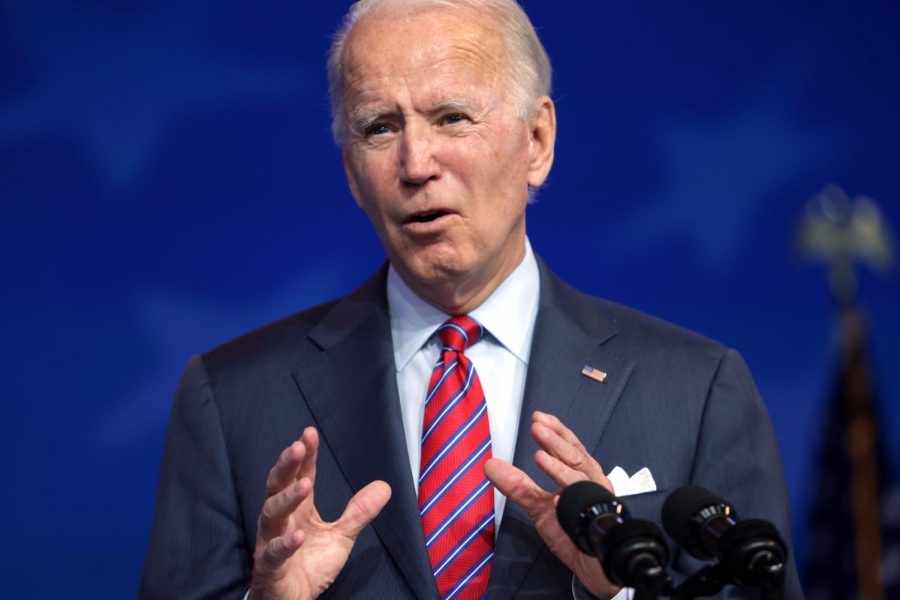

President-elect Joe Biden speaks in Wilmington, Delaware, on Friday, Dec. 4, 2020. (Alex Wong/Getty Images/TNS)

Late Thursday, Oct. 10, the notification popped onto my phone: Glenn Greenwald, the heroic, cynical journalist who broke the Edward Snowden National Security Agency bombshells in 2013, just lost his job.

Greenwald had resigned from his post as co-founder and columnist at The Intercept, the independent journalism experiment he created in 2013 with Jeremy Scahill and Lauren Poitras. It was a baffling decision. From 2014-2017, Greenwald raked in an average of $400,000 a year, and his salary has likely remained similar since then.

Greenwald is an iconoclast, seen in his incisive, damning exit think-piece. In a lengthy post on his new Substack page, the “as-of-now” new home for Greenwald’s journalism, he explained in great detail his history at The Intercept and “the final, precipitating cause” of his resignation.

According to Greenwald, the reason for his departure was censorship of the last article he wrote for the online publication. The piece in question — now uploaded to his Substack — analyzes The New York Post’s reporting on Hunter and Joe Biden’s possible misconduct during the Obama administration. Greenwald published emails with Intercept editors about the story, which show the disagreement pretty clearly.

Peter Maass, an Intercept editor, responds to Greenwald’s article via email, taking issue with it and instructing him to shift the article’s focus. Greenwald gives his evidence and marks the response as part of a pattern of misinformation and censorship by Intercept editors. Intercept Editor-in-Chief Betsy Reed responds to Greenwald, telling him that editors expected him to edit the article, that “it would be unfortunate and detrimental to The Intercept for this story to be published elsewhere” and that his comments about the publication and its employees were “unacceptable.” Greenwald responds with his letter of resignation.

The Intercept’s short history is fraught with insolvency, internal conflict and general bad blood. An unprecedented experiment in journalistic freedom, it suffered a rocky start but seemed to find its footing after a few years. Greenwald, however, posits that it strayed from its original mission and ethos, citing the deeply embarrassing Reality Winner debacle and the publication’s treatment of its journalists, among other items.

Here is the setting for Greenwald’s explosive exit: As his relationships with editors deteriorated, he became more and more disillusioned with the publication he founded. From his home in Rio de Janeiro, his snipes at distant, impersonal Intercept editors and contributors became more and more public. Finally, enough was enough; he parted ways.

In response to Greenwald’s withering resignation, Reed published a response on The Intercept’s website, excoriating him:

“We have the greatest respect for the journalist Glenn Greenwald used to be, and we remain proud of much of the work we did with him over the past six years,” Reed wrote. “It is Glenn who has strayed from his original journalistic roots, not The Intercept.”

I’m not so sure about that.

Greenwald’s original article has, in my view, close to nothing wrong with it. As a columnist, he did the exact thing I’m doing now: he presented evidence as given by multiple sources, then used his judgment and reasoning to draw conclusions from it. Most of the editors’ gripes — the more thoughtful ones — are with Greenwald’s analysis of evidence.

Now, Greenwald’s extraordinarily permissive contract aside — he was entitled to publish almost anything he wanted at The Intercept — this seems like a gross overreach of editorial power. I edit columns for The Communicator. I have pushed back at columnists and poked at their reasoning, but I would never dictate what opinions they could publish. It would be obscene.

Furthermore, Greenwald’s reasoning is… reasonable. He makes no outrageous or unfounded claims of corruption or collusion. They’re actually pretty tame: his piece is mostly media criticism, with his assertion that The Post’s documents “raise important questions” mostly functioning to condemn what he saw as a partisan cover-up campaign.

Greenwald’s reasoning isn’t the real issue with his article. It’s his opinion. He reported on a nasty opposition research piece in the middle of a hotly contested presidential race. The problem? He picked an unacceptable candidate to criticize.

There is an ugly problem in American journalism that no one names, probably because of its pervasiveness. Publications have always and will always have editorial stances, and brilliant journalism persists. The problem comes when those stances are so polarized and so specific that intellectual diversity is extinguished.

Generally, I abhor polarization discourse; I still think more unites Americans than divides us, even if the things that divide us are incredibly pernicious. However, when it comes to the media, our country is actually polarized — demonstrably so.

According to Pew Research Center, the two news sources identified by most Americans as a primary source of news, Fox and CNN, each have under 20% viewership from one party; Fox News’s audience is only 6% Democrat. As a political duopoly, each party is increasingly receiving its news from a single, polarized source.

The extreme of this is a breakdown of a fundamental concept of truth that Americans have completely lost. There are, at any given moment, at least two truths in the mainstream media; the one that outlets like CNN and The New York Times publish, and the one that outlets like Fox News and The Wall Street Journal publish. How do we know this is so pervasive?

The Intercept, by mission statement and driving ethos, is a publication explicitly in support of the freedom of journalists to cover and publish what they wish. They just essentially fired their most famous journalist over opinions expressed in a column.

The question is not whether the media is dangerously intolerant — it’s who will it spare.