Treating Patients with COVID-19

My father stood with a huge plastic hood over his head, waiting, as he had done every year since medical school, to see if he would smell the pungent odor being pumped into it.

“Can you smell this?” An aggressively sweet scent flooded his senses.

“Yes.”

His brand new N95 mask was strapped tightly around his face. They placed the hood over his head again, and the sickly sweet scent was released once more.

“Can you smell it now?”

“No.”

The mask fit and was ready for use. The N95 keeps out smaller particles than a regular hospital mask, so it is more effective at preventing diseases that can be transmitted through the air, like COVID-19. The uncomfortable mask is now an absolute necessity for health-care workers during this pandemic.

On the Sunday of every second week, my dad finishes his break and goes back to work at Michigan Medicine. My dad, a neurologist, had been conducting regular patient visits from home. But this week he’s on the in-hospital consult service, seeing patients who are sick with COVID-19. Monday, as he walked up to the front door in his hospital mask and scrubs, he was asked how he felt. He responded that he is feeling fine, but his temperature was taken at the door. He was told to wash his hands and was given a new hospital mask for the day. His scrubs, gloves and mask would be absolute necessities for the next week, and he would put on and take off these items countless times, as he began to regularly treat patients with COVID-19.

“I keep that mask on all day unless I really need to change it,” he says. “It gets really annoying, and if you sneeze or cough into it, it smells really bad.”

The biggest risk for health-care workers during this pandemic is seeing patients who haven’t yet been tested for the disease. Doctors have to give exams in close quarters with possible COVID-19 patients, while only wearing a hospital mask and scrubs.

“When we get a call to go see a neurology patient, in the emergency room or in the hospital, usually the resident will just go and see the patient, take the history, examine them, and then come talk to me about it. We’ll discuss it and then go see the patient together,” he said. “But now we are trying to limit our exposure to possible COVID patients. When we get the call to go see a patient, the first question that we try to answer is whether or not we think that physically examining the patient is likely to change our decision-making about them. Of course, you don’t really know until you see them, so you’re kind of making your best guess.”

If a patient has a stroke, a physical exam is necessary, and the patient cannot be treated without one. In this case, someone like my dad would be sent to examine them. But if someone comes in with a migraine, the exam may not be necessary and recommendations can be given over the phone. As they decide whether to visit a patient in person, health care providers can also rely on the hospital’s new classification system for its patients. Every patient at Michigan Medicine is now listed as: “COVID positive”, “COVID negative”, “being tested” or “not being tested.” (**Note: since our first conversation, my dad reports that every patient admitted the hospital is now being tested for COVID.)

“PUI is basically what we call a ‘patient under investigation,’” he said. “This means we’re worried they have COVID, and we are testing them, but don’t have the results yet.”

In this scenario, they try to wait for the test results before any in-person contact, but if an immediate exam is absolutely necessary, they must change into full PPE (personal protective equipment) before heading into the room.

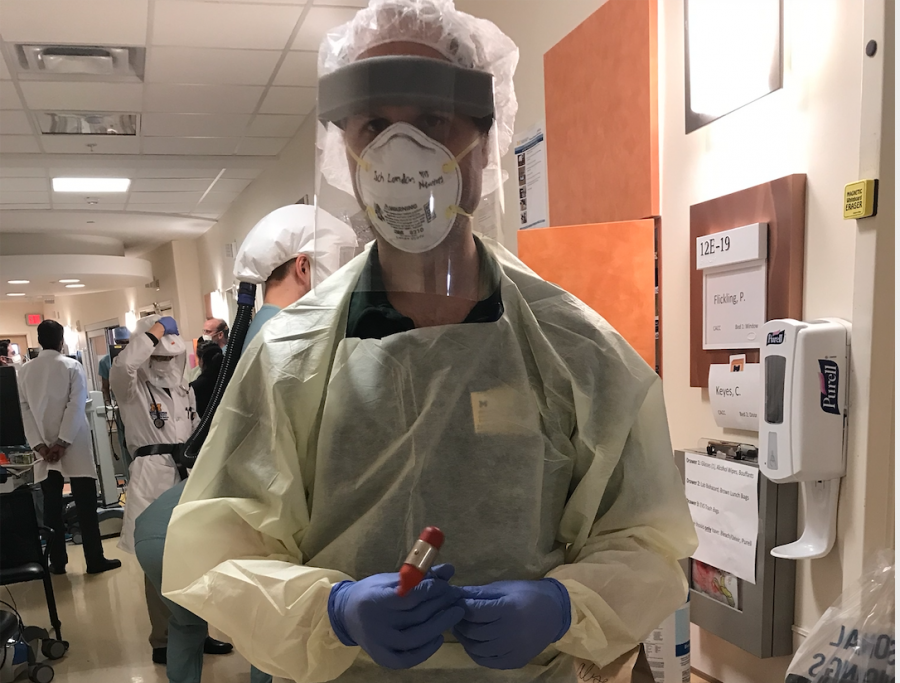

When treating a COVID positive patient or a PUI there is a very particular order to preparing for the exam and changing into full PPE.

“The first thing I want to do is make sure I know everything that I need to know before I go in the room, so I don’t have to go in more than once,” he said. “We have this process of putting on PPE and the process goes like this. You go into the hallway outside a patient’s room, wash your hands, take off your hospital mask and put on a disposable gown. You roll the sleeves up on this disposable gown with your bare hands. Then, you put on gloves, and your N95 mask. I carry mine around in a little lunch bag with my name on it. So, I open the bag, I take out the N95–not touching the mask, just touching the straps–as I put it on. Then, you take off the gloves and wash your hands again. Then comes the eye shield, which I also carry around in a bag. The mask is considered contaminated at all times, but the eye shield gets washed after every use. The eyeshield has a soft foam part that goes on your forehead and a big visor that covers your entire face. Last, you put your gloves on and you’re ready.”

This process is usually completed more than once every day, and it can get very uncomfortable to keep putting on and taking off all of this equipment. But most of these things are not new to doctors.

“I’ve been taking care of patients my entire career where I have to do most of this, just putting on a mask, gown, gloves and occasionally goggles when you enter a room,” he said. “The only differences here are the actual N95 mask, the full face shield and the fact that we’re reusing them.”

Although the process of applying full PPE to see COVID patients sounds lengthy and scary, it’s reassuring to know that health care professionals are used to this.

“Infectious disease in the U.S. is nothing new; health care professionals know how to do this,” he said. “It’s just more at the forefront of our national consciousness now that we’re living in a pandemic.”