“Piranesi” Review

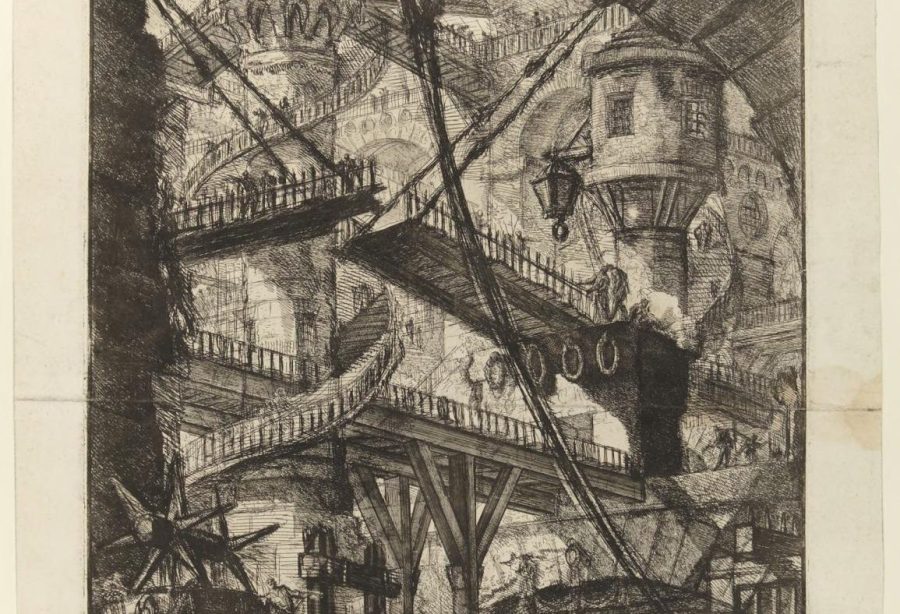

One of Giovanni Piranesi’s fictional prisons; the main inspiration for “Piranesi”‘s imagery. The Drawbridge, 1761 Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Italian, 1720–1778 Etching plate: 54.5 x 40.7 cm. (21 7/16 x 16 in.) sheet: 64 x 49.2 cm. (25 3/16 x 19 3/8 in.) frame: 77.5 × 62.2 × 2.5 cm (30 1/2 × 24 1/2 × 1 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1938-13 g

Piranesi lives in a mystical House. This is not just any house but a whole world contained in one infinite maze of halls. The ocean rushes freely through the House’s marble, Greek-facade corridors. Its halls stretch infinitely in every direction; its top floors touch the clouds, and its bottom is drowned in the ocean’s tides. Piranesi knows the House inside and out, but he doesn’t know much else. Even the moniker “Piranesi” is not his name, but a cruel reference to an eighteenth-century artist — famous for drawings of intricate, fictitious prisons — who, as far as he knows, does not exist, for Piranesi’s world is small. The universe contains only the House, its statues, one person “Other,” and thirteen people dead.

This novel, “Piranesi,” is the newest endeavor by Susanna Clarke, a British author known for her critically lauded debut, “Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norell.” Written in the isolation of debilitating, long-term illness and published in the isolation of 2020’s full lockdowns, it’s a fantasy, a mystery, a naturalist’s delight — and more than anything, a book about being alone with yourself and the world.

For a book so rooted in isolation, though, “Piranesi” is not claustrophobic or depressing; rather, it is the complete opposite. Piranesi knows nothing but isolation, so every detail of his life brings him great joy. He loves the sea creatures in the tides and the expanses of the halls. At heart, he is a scientist, a stenographer of the language of birds and statues spoken by the House.

Clarke, clearly having spent plenty of time in Piranesi’s world, familiarizes us with it through his eyes in intimate detail. The imagery of the House is highly memorable not only because of its content but also its narration — Piranesi is a true naif, going about his life with perfect curious innocence, and that naivete makes it possible for the reader to take in every detail as Piranesi sees them.

Of course, not everything is as it seems in Piranesi’s world, and the peace in which he lives is soon disrupted by cryptic messages from the House, long-lost memories of his own, and a possible Sixteenth Person (!) in in the universe. The book’s mystery, though it won’t be detailed here, is as masterfully developed as its scenery. Clarke is a master at keeping you guessing, both at what comes next and at Piranesi’s ability to truly report what’s happening— perfect naivete makes for an unreliable narrator, and even as Piranesi’s narration is beautiful, it’s constantly called into question. In hindsight, though, everything will be made clear, for “Piranesi” is one of those satisfying books where you can look back after being surprised and see every piece of foreshadowing you missed on the way.

In any case: if you’re a nature lover, a journalist, a scientist, read this book. If you’re a C.S. Lewis or J.K. Rowling enthusiast, read this book. If you were a little too interested in Greek myths in middle school, definitely read this book.

It will be the most interesting thing you’ve read in a good long while.

“Piranesi” is 245 pages and available from the Ann Arbor Public Library.