Redefining History at Community High School

Art by Mia Wood

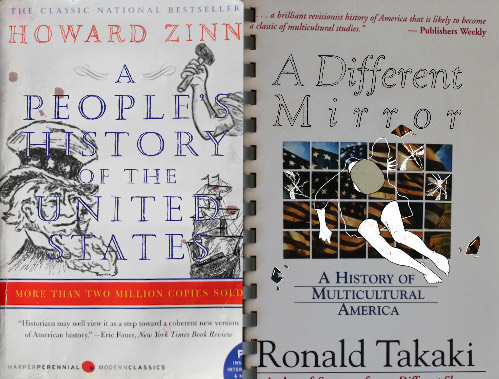

A turning point for the U.S. history curriculum at Community High School (CHS) came in 1994 when senior Sasha Polakow-Suransky approached history teacher Marion Evashevski with a new idea: He wanted to develop a new history class that flipped the script on U.S. History by bringing the perspectives of minorities and people left out of the current curriculum to the forefront. He had been reading Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States,” and Ronald Takaki’s “A Different Mirror,” two alternative U.S. history textbooks.

“[Those books] were a bit of a revelation, in that [they were] the complete flip side of the narrative and the traditional history textbooks,” Polakow-Suransky said. “And so I thought, ‘let’s get more of this, let’s use these as textbooks.’”

Polakow-Suransky was frustrated with how history textbooks failed to cover certain historical episodes, characters or personalities. He knew that Evashevski, more than most teachers, made an effort to cover different historical perspectives in her regular classes by using supplementary materials. “A People’s History of the United States” and “A Different Mirror” were two of the only alternative history textbooks that were also comprehensive, covering more than a narrow period or topic.

Evashevski was enthusiastic about the idea and asked Polakow-Suransky if he wanted to co-teach the class. He said yes.

“He single-handedly wrote the grant that got us the two textbooks,” Evashevski said.

The class was called U.S. History: Minority Perspective, and it was an immediate hit. Within two years, all of the U.S. history classes began using Evashevski and Polakow-Suransky’s curriculum.

When Robbie Stapleton was hired at CHS in 1987, the history department looked different than it does today. There were a wealth of electives: Western Civilization, Non-Western Civilization, Civics, Psychology, Peace Studies, Model UN and more. In 2000, the district put a cap on how many classes a student could take: 6 classes, plus forum. On top of that, there were new requirements on classes a student needed to take to graduate. All of those requirements left less room in students’ schedules for electives.

When Stapleton began teaching U.S. History, she enjoyed more academic freedom than teachers at other schools.

“I could use my own resources, I could use journal articles and primary sources,” Stapleton said. “That’s what I really loved about the freedom at Community. I didn’t feel constrained by district requirements or state [requirements]. We all had to teach the required courses, of course, but what I loved about it was that I wasn’t wedded to a textbook.”

History teachers at CHS did not have to take the common assessment, did not have to sync their classes with each other and did not have to use regular history textbooks. They were able to offer their students a version of their classes that included the perspective of Americans who had been left out of the story. Stapleton also offered independent studies that covered topics like the 1960s, racism, sexism and environmentalism.

When Stapleton reflects on the controversy surrounding how U.S. history is taught in the country today, she feels like what she and her colleagues were teaching was not out of the ordinary.

“We were really committed to the idea that this is not women’s history,” Stapleton said. “This is not African American history. This is not indigenous American history. This is American history. And, of course, these stories should be told, because we’re all Americans.”

Another former CHS history teacher, Cindy Haidu-Banks, also watched her curricular freedom slowly disappear throughout her 20 years at CHS. She found herself having to adjust her schedule to fit state-mandated tests that collected data on her students, and she was required to cover a certain time period in history by the end of the first semester.

At the start of her career, Haidu-Banks could spend an extra week on the Great Depression, for example, depending on what her students were interested in, but by the end of her career, there was less wiggle room in her curriculum. She felt more stress and tension in her teaching and less joy. While she loved teaching until she retired in 2020, she felt that state requirements for testing and data collection were taking away time that she could have spent with her students, teaching more valuable topics.

When she looks back on her time at CHS, Haidu-Banks is happy with how she left the history department. Despite having to follow state requirements, she was committed to teaching the harsher truths of history, and not only the progress the US has made, but where work still needs to be done and why.

“I’m proud of us,” Haidu-Banks said. “I’m proud of Chloe and proud of Ryan. I feel like all the teachers have embraced in a passionate way that they’re still going to encourage the students to question what’s being taught and how it’s being taught. ‘Is this the real story? Is there more to this story?’”

Haidu-Banks knew she could retire when Sarah Hechler was next in line for her job. It felt fated to her that Hechler arrived while Haidu-Banks had her own reasons for retiring.

“I was leaving my forum in good hands [and the] history [department] in good hands,” Haidu-Banks said.