Reflections in the Glass

Four CHS students share their experiences as dancers: stereotypes, mirrors, recitals and practice.

Lila:

Lila Ryan has been dancing since she was two years old. Since the time she learned to walk, her love for the sport has only grown. Memories of Nutcracker performances, solos, competitions and time spent with teammates remind her constantly of why she has dedicated so much of her life to dance. However, not all aspects of Ryan’s dance experience have been quite so positive. Growing up in the dance community, she noticed early on a culture of comparison, especially when it comes to body image. In her experience, this comparison can even be internal, her past self competing with her present.

“Once I hit around eighth grade, and I started growing into my body a lot more, I started noticing, ‘wow, I can’t get my leg as high up anymore because there’s more there,’” Ryan said. “I grew [a lot] over a year, so [from] eighth grade to my sophomore year, there was such a big difference that I thought there was something wrong.”

Though she has noticed similar issues across all genres of dance, Ryan has found the ballet environment to be particularly toxic.

“I think all of ballet has stemmed from this elitist idea that only the skinniest, prettiest and whitest of dancers can really be a ballerina,” Ryan said.

The professional ballerinas that young dancers grow up seeing often propagate this same image. In Ryan’s case, seeing only one type of body represented in the professional ballet world made her feel as though she needed to change her own body to match this image.

“To be a dancer, you feel like you have to look a certain way and fit into a box, and when you don’t, it’s harder for you to see yourself dancing more than just in high school,” Ryan said.

Since she finds this professional image unlikely to change, Ryan hopes instead that change in the dance community will come from the way instructors and studios teach young dancers.

“My teachers have always been body positive and inclusive and loving for everyone,” Ryan said. “They’re like my second family.”

The positive environment in her studio helped Ryan to work through her own struggles with self-comparison. She hopes other young performers will have the same support.

Marisa:

Marisa Andoni-Savas started dancing at three and a half years old, taking private lessons. In fifth grade, she moved to Randazzo Dance Studio where she was immediately accepted into their dance community. Being in a studio with a community, Andoni-Savas has been able to connect with dance much more.

Andoni-Savas does all genres of dance, with classes up to [how many times a week?]. Her current favorite genres are lyrical and modern.

“[Lyrical and modern are] not a lot about the technique;, it’s about showing your emotions and having your audience feel you,” Andoni-Savas said. “Being able to share that and share my dance with people is really exciting for me.”

Andoni-Savas has learned to express herself through dance and how dance can be an outlet for her.

“It’s a really big stress reliever for me,” Andoni-Savas said. “Whenever I feel really stressed, I’ll go to my dance studio, I’ll just do some stretches, and I’ll try to dance it out. It’s easy to just let go.”

She sees dance as a part of her future, though she is unsure whether that will include dancing or choreographing, or both. Currently Andoni-Savas teaches classes to younger girls at her studio. At recitals, she enjoys seeing what she has taught, and also what she has learned.

“Before [a recital], I feel really excited; there’s not a lot of nervous feelings,” Andoni-Savas said. “I’m just like, ‘whatever happens, it happens. I’m dancing; this is what I love so it’s going to be fine either way.’ During [the performance], it goes by really quickly for me. I always forget everything that happens, and then after I’m relieved that it’s over.”

After recitals, she moves on to thinking about the next class, the next recital and the next thing to learn.

When learning, Andoni-Savas sees mirrors as an advantage in dance: a way to show technique and correct yourself. Mirrors would not fit in other sports the same way as they do in dance. She has found mirrors helpful when learning, but feels she is too dependent on them.

If I want to go pro, mirrors aren’t going to be a big thing that [all] studios have,” Andoni-Savas said. “So having a mirror is a big advantage and something I’m really grateful for, but I need to start learning to use my muscle memory so I can start transferring all the movements when mirrors go away.”

Though Andoni-Savas sees mirrors as an advantage right now, they present additional challenges for her.

“We’re putting our bodies on display; dancing for people is all about the body,” Andoni-Savas. “It really depends on the person whether or not they’re comfortable just putting their body out there. Some people are a little less comfortable with that, and some people are really okay with that, but I think having a mirror for me is a big struggle because I’m constantly looking and I’m like, ‘Well that’s wrong; I need to fix it,’ but sometimes I need to do it by muscle memory instead of with a mirror. I’m never really learning the mistakes I’m making; I’m just looking at the mirror and saying that looks wrong so let’s fix it.”

Morgan:

When Morgan McClease was in fifth grade, she was told for the first time, “you don’t look like a dancer.” At ten years old, McClease had been dancing for seven years, longer than she could remember. However, for the first time, she became very conscious of her body and began to wonder why it did not look like the ballerinas she saw on the stage.

McClease spent hours each week in the studio, learning different styles of dance. But as she learned to perform lyrical, musical theater, tap, jazz and ballet, she also learned to compare herself to the other dancers around her.

“You’re in a leotard and tights, so it’s super tight on your body and you can see every flaw and imperfection that everyone has,” McClease said. “There’s also this huge mirror in the studio, and you’re constantly looking at yourself.”

McClease struggles with the idea that she had to change herself to be a successful dancer. Within the dance community, she became conscious of a standard of perfection early on. In her experience, dancers tend to hold themselves and each other to unattainable standards.

“I’m a perfectionist, and dance is something that no one is ever completely perfect at,” McClease said.

Dealing with her own and others’ standards has been difficult for McClease. Though for the most part her teachers have been very supportive and loving, the dance community as a whole has had a significant influence on McClease’s dance experience, often causing her and many of her peers to feel as though they are not skinny enough, not pretty enough or not talented enough.

“I feel like if you don’t look a certain way, it’s a lot harder for you in the dance world,” McCClease said. “You’re treated differently.”

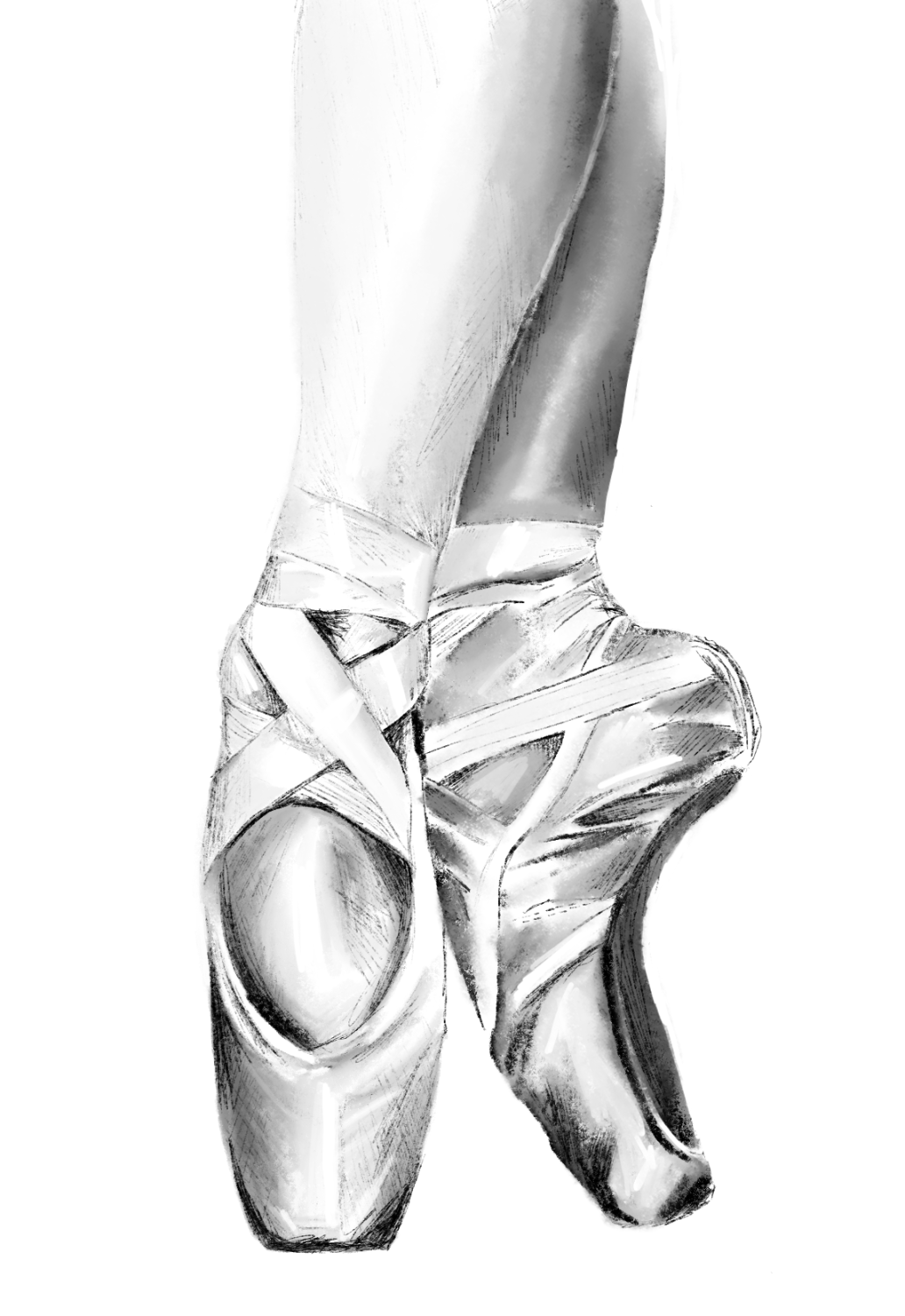

This standard associated with ballet, and dance in general, presents itself in unique ways, often unknown to those outside the dance community. Even seemingly arbitrary aspects of dance, such as the shoes performers wear, contribute to the often harmful image of the “perfect dancer.”

“They make pointe shoes in this light pink color to match a white person’s [skin], and then if you are a person of color, you have to change the color of every point shoe,” McClease said.

Using foundation to change the color of pointe shoes has become another way in which dancers must conform to a universal standard.

Owen:

“Dance is a test of grit — if you’re willing to do everything you can to push through and still look the best you can,” Provenzola said.

Owen Provenzola started dancing at five years old at Randazzo Dance Studio. Since then, he has only taken one break from dance when he broke his leg in gymnastics in fifth grade.

“When I came back to do gymnastics and ballet, it just felt [like] so much,” Provenzola said. “I would lose my balance; I would fall; I would have a harder time doing anything. Being there after years and years, it makes you realize that [dance] is a constant maintaining of strength and balance that makes you so much stronger.”

After his injury, returning to both dance and gymnastics was too overwhelming and in seventh grade he chose to pursue only dance. Though being a gymnast built strength he still uses in dance. He has found a community and family at Randazzo Dance Studio where he is supported and motivated to get better and push through challenges.

“Whenever I go out and dance, it always forces [me] to be there and be present,” Provenzola said. “You have to be in the moment; you have to think about every muscle and every step. You don’t ever want to fall behind, and I think that’s one of the things that pushes me.”

Provenzola performs in recitals once a year in the spring. As recital season approaches, his practices pick up and can become stressful. Provenzola gets nervous at his recitals, but when he walks onto the stage and the lights shine on him, he blurs out the audience and focuses on dancing.

“I want to be the best I can and I don’t want to be a blank dancer,” Provenzola said. “[I want to] do something so people see me.”

A large factor in Provenzola’s growth in dance is mirrors. In his basement he uses mirrors to practice; they are a resource that is always there for him. For him, the mirror’s purpose is correcting his dance. This has helped him improve as a dancer.

Over the years Provenzola’s goal in dance has shifted from getting as strong as he can and to look good while dancing to his current goal: persevering to improve and reach his goals. When Provenzola watches a captivating dancer, he feels inspired and wants to reach that level of an influential performance.

As Provenzola’s goals in dance shifted over the years, he learned to embrace his identity as a dancer. For this reason, it is frustrating for Provenzola when people assume his sexuality purely based on his sport.

“[Dance] is a female-dominant sport, [and] in the U.S. it’s not as glorified as other places; In Russia or Japan [dance is] awesome, but here people just assume [my sexuality],” Provenzola said. “[These stereotypes] made me self conscious to talk about [dance]. Up until eighth grade, I felt self conscious about it. My best friend for years didn’t even know [that I danced], but now I’ve embraced it. I am a dancer, and I like [dancing], and it’s something that should be glorified.”