History of AP

HISTORY OF AP Three former CHS teachers describe their experience with Advanced Placement classes and why they believe Community is better off without them.

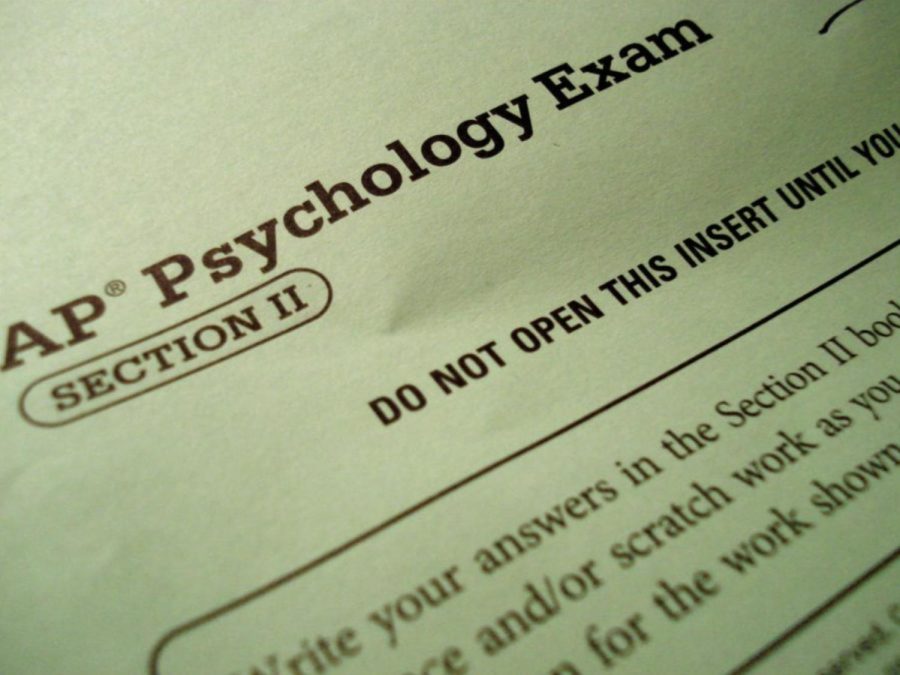

College Board administered the first Advanced Placement (AP) tests to 27 high schools in 1954 as part of a pilot program. Last year, 22,169 schools offered AP classes to prepare students for those tests. CHS was not one of them. Although these classes have become a core part of the curriculum at all three of the other high schools in the AAPS district, they have not spread to CHS due to the separations they create within the student body and the negative impact that those separations can have.

When Judith DeWoskin first started her job as an English teacher at CHS in 1984, it was widely accepted by teachers and students that there were no AP classes offered. DeWoskin felt that part of the reason for this was that teachers at CHS wanted to offer their own classes with curriculum they made.

“Nobody was particularly interested in it because we felt that the material in our courses was generated by the passion we had for certain content,” DeWoskin said. “If you teach an AP class, the curriculum is given to you. We wanted to do it ourselves.”

DeWoskin had taught a variety of English classes throughout the 36 years she spent at CHS. She believes the goal of any good class should be to reach as many students as possible. By offering AP classes, DeWoskin feels there is an assumption that the brightest kids are put on a pedestal and the kids who are below that level feel discouraged and don’t have the opportunity to expand to their potential.

Carolyn Siebers, a former math teacher at CHS, agrees with DeWoskin.

“I believe that all those divisors are artificial,” Siebers said. “Who am I to judge who’s an excellent student and who’s just regular?”

Siebers taught math at CHS starting in 1981 and has seen the firsthand impact separations can have on students. Many years ago, CHS had extra support math classes for students who were deemed unready for Algebra 1, such as Consumer Math and General Math. CHS eliminated all of these classes during the 1986-87 school year.

Siebers believed these classes were a “failure ground” for students because they grouped students together who had been previously unsuccessful in school or simply didn’t like school. Siebers kept data on the math courses at CHS and

began to see that fewer students were failing math each year after all students started with Algebra 1. The year before the classes were eliminated, 45 students failed their first-year math course, but after the classes were eliminated, that number significantly decreased to 25 students.

Siebers believes that when students are divided by level, the normal diversity of skill sets are removed; when all the brightest students elect to take more advanced classes, the positive role models and the leaders are also lost.

Siebers believes that having classes with a mix of different skill levels benefits the brighter students in a class as much as the other students. She argues that the leaders and the go-getters also benefit by staying in these classes because they get to reinforce their education by teaching and working with their peers.

Both Siebers and DeWoskin do not remember ever feeling pressure from the district to start an AP program at CHS. Siebers, however, did occasionally feel there was a level of disrespect for CHS from faculty from other AAPS schools. As the head of the CHS math department, she attended many district-wide meetings. When Siebers argued that a wider variety of kids could take upper-level classes, she sometimes felt other teachers and administrators believed their courses were more rigorous or more advanced than the courses at CHS.

Anne Thomas, another retired CHS math teacher, thinks one of the main reasons CHS never had an AP program is due to Community Resource of opportunities and the ability for CHS students to take classes at the University of Michigan (UM) and Washtenaw Community College (WCC).

Thomas believes that it is not necessary for students to take AP classes in preparation for college. She has seen many of her students and others excel in college and she feels her own daughter was thoroughly prepared to go to college after going through CHS’ curriculum. Thomas believes her daughter left CHS loving learning, and, to her, that is far more valuable than an AP exam.

“If a department is strong and they’re really inspiring kids to learn and preparing them well for college, then they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing,” Thomas said.

Although AP classes are not offered at CHS, some students still opt to take an AP exam at the end of the year. These students typically self-study for the test or dual-enroll at their home school to take an AP class. CHS classes that line up with the AP-based classes are sometimes taught to prepare their students for the AP test throughout the year. Math teachers at CHS have been preparing their calculus students for the AP exam since 1985 when calculus first became a class at CHS.

Siebers began teaching calculus in 1989. She estimates around 25% of the students in her calculus class took the AP test every year. To prepare her students for the test, Siebers would attend AP conferences and gather old AP exams for her students to practice. After Siebers retired, Thomas started teaching calculus and also began to prepare her students for the AP exam. Thomas offered extra office hours and stayed after school to help students in the weeks leading up to the exam.

Although they opposed the separation of students into different class levels, DeWoskin, Thomas and Siebers were not directly opposed to the idea of students taking AP classes and exams; they just didn’t believe it was the right decision to have them at CHS.

“There were students going to Huron and Pioneer to take AP classes, and we didn’t have any problems with that,” DeWoskin said. “We were just trying to be a little more inclusive [at CHS].”

Siebers, Thomas, and DeWoskin have all found success through teaching students with a diverse range of academic abilities at CHS. All three believe that every student has the potential to succeed and that having different levels of classes creates an unnecessary separation.