Housing Segregation in Ann Arbor

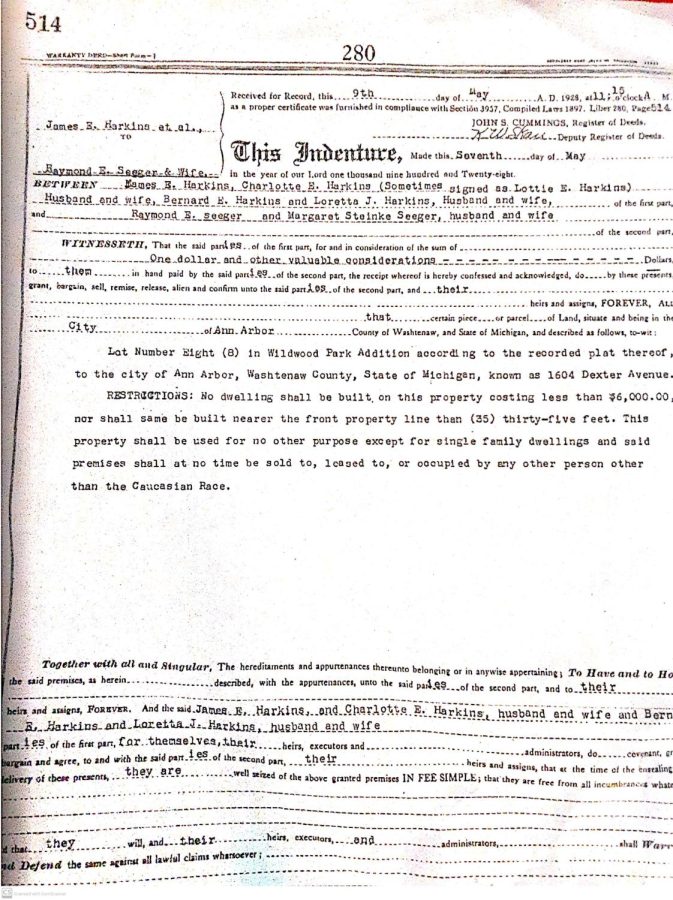

In Ann Arbor, and across the country, exist thousands of deeds restricting the sale of property by race. Hidden in historic documents and city archives, these racially restrictive covenants serve as a reminder of a segregated past and are the focus of Justice InDeed, a project dedicated to raising awareness of and repealing the covenants.

“We want to create a future that is more inclusive and diverse and that is true to these values that Ann Arbor proceeds to espouse, which is that this is a place where everyone’s welcome,” said Nina Gerdes, an incoming third-year law student at the University of Michigan and a student attorney with the Civil Rights Litigation Initiative [CRLI]. “Part of these projects with neighborhoods specifically, where we have repealed these covenants or replaced them with more inclusive language, it has been in an effort to communicate that we are moving forward in a direction that is more inclusive and where everyone is welcome at these communities and where neighborhoods are really affirming these values and shaping a more positive future.“

Gerdes became interested in fair housing during undergrad when she researched redlining in Chicago and the impact of older legislative acts on current city funds distribution and racial demographics.

“After doing some of that work, I decided that I wanted to go to law school and learn more about housing law and how people’s civil rights had been and continue to be violated by people who can use the law for evil rather than good,” Gerdes said. “Joining the clinic, I was really excited to hopefully get started on some housing law projects. And that’s when Mike [Mike Steinberg, director of CRLI] approached me about Justice InDeed.“

Matthew Countryman, the chair of the University of Michigan Department of Afro-American and African Studies, is on the board of Justice InDeed. He was also an organizer of Black Washtenaw County, a long-term collaborative project that started in September 2021 relating historical questions about the history of housing segregation and asking how history can be used to inform efforts to address current racial inequality.

“The reason we did the BWC project, in part, is because we didn’t want the story of the covenants to be told in isolation,¨ Countryman said. ¨The covenants are one of the most important tools that were used in the years before the 1960s to enforce racial segregation. But they were neither the first nor the only tool that was used. We want to tell that story and address the question of why they remain on deeds in important parts of the county, from the context of seeing them not as everything will be fixed if we get rid of them, but rather we need to understand they are one of a number of tools and techniques that have been used to structure racial inequality.¨

Countryman says he and his team have always felt that it is not simply enough to remove the covenants if you don’t also address the causes and continuation of racial inequality.

A major principle of Black Washtenaw County is to tell the whole story and center Ypsilanti, the oldest and largest Black community in the county. Countryman says due to disparities in wealth and the presence of the university, Ann Arbor can overtake and hide the importance of Ypsilanti’s story.

“We were reminded that you couldn’t tell the story of Black Washtenaw County or racial segregation without telling the story of Ypsilanti and Willow Run, and those histories in the eastern part of the county,” Countryman said.

Justice InDeed’s most recent project was with the Hannah subdivision, a neighborhood close to the university campus. After contacting Steinberg, residents of Hannah learned they lived with a communal (neighborhood-wide) restriction and began work to repeal it.

In the beginning, Gerdes says, there was shock and many questions about why it was important to repeal a no-longer enforced restriction. But after open community conversations and neighborhood outreach, there was no opposition and everyone who could sign the amendment did so.

The question the clinic and Justice InDeed receive most is, “Why does this still matter?“. The covenants are not enforceable or legal anymore, but Gerdes says they still impact communities.

“Many of the communities that we have worked with that have racially restrictive covenants that restrict on the basis of race and color and national origin, are much less diverse than areas that don’t have racially restrictive covenants,“ Gerdes said. “So a big issue is that it has bled into today and that is something that is hidden and not really seen in the public eye. Part of our mission is to raise this awareness and show this community that even though Ann Arbor has this reputation of being so liberal and so inclusive and diverse, there are still these long-lasting, insidious effects.“

Next Justice InDeed hopes to create a toolkit so residents can become more independent through the process of repealing covenants. The documents that contain the covenants, while public records, can be hard to access due to covenants being redacted by title companies or handwritten. Next fall, Gerdes hopes they will have opportunities for volunteers to go through documents and find covenants.

Moving forward with Black Washtenaw County, Countryman says he is cognizant that the histories and stories belong to the communities, and not university researchers. They are not telling stories that have not already been shared but are instead gathering previous work to make it more accessible, and working with pre-existing organizations such as the African American Cultural and Historical Museum of Washtenaw County.

“That’s an ethical responsibility for all of us not to conduct research in a way that simply extracts it from communities, but rather does it collaboratively and does it in ways that benefits all of us,” Countryman said. “We call it the principle of mutual benefit. The results of the research, of the scholarship, have to help every community involved and every individual.”

Because Black Washtenaw County is a newly started, long-term project, residents can expect to learn more about it in the coming years.

“We’re just beginning to work on it,” Countryman said. “It’s been a year now. We hope in the next year or so to have a lot more resources available through the Internet and other sources and to continue to build the collaboration between community organizations and the university. Hopefully, folks will hear a lot about this project in the future.”

Gerdes hopes all residents will continue to think about and confront the history of housing in Ann Arbor and be open to conversations on how to remedy the impacts of history.

“It’s really important to reckon with the history of an area, either if you’re a longtime resident or if you’re a new resident,“ Gerdes said. “I think [for], particularly students at the university, either undergrad or grad students, it’s really important to understand the background and why racial demographics look the way that they look, why communities have developed the way they do and it’s important to be clear that even in an area like Ann Arbor, that is super socially liberal and inclusive and diverse, there are still these traces of this ugly history.“