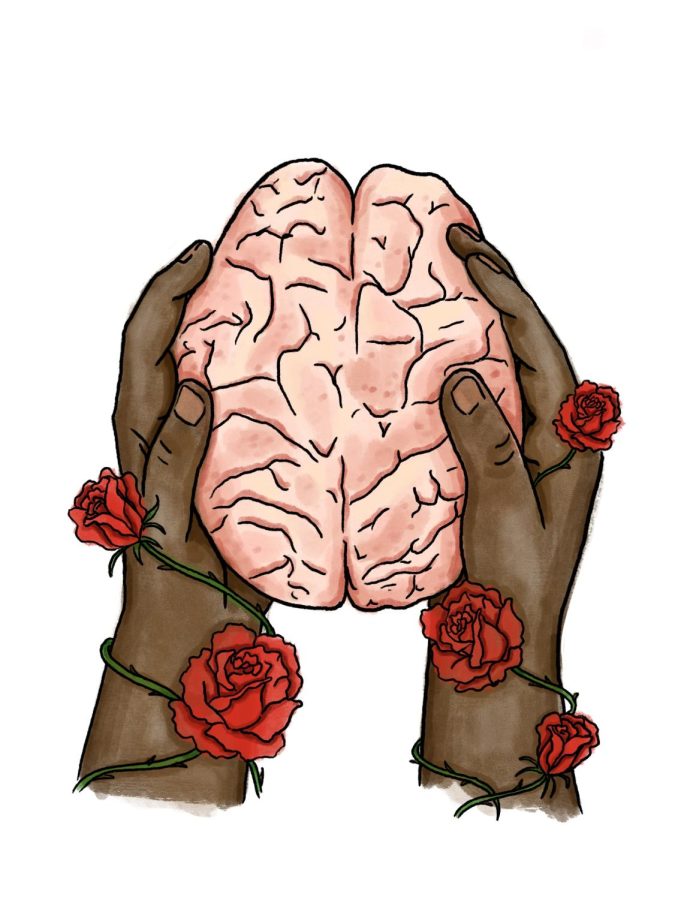

The Hands That Get To Heal

Art by Ryan Thomas-Palmer

Being human is to be a collection of your experiences, memories and truths. This collection can be ugly and simultaneously beautiful.

Generation after generation that load is passed down to next of kin. Some experiences are heavier than others and harder to carry. Some leave your hands more rigid, backs more sore, body more scraped and soul inherently more resilient.

Naturally, we’re taught to try to lighten the load.

When you’re a racial minority in this country you’re forced to carry the reputation of yourself along with your community.

Zion Dottery, CHS junior, knows his identities subsequently means he has to carry more than others.

He is Black and gay.

Mental health struggles place one more identity of heavier weight.

Growing up, Dottery was taught to suppress his emotions. The Black community, like other communities of color, are placed under immense pressure to prove their worth.

“You’re already Black,” Dottery said. “That’s already something that [is] frowned upon. Do you want to add on the fact that you have mental health issues? That’s just enough reason for white people to look down on you.”

This suppression of emotions took a toll on Dottery. Growing up, the people around him would instill the practice to hide his emotions. He was taught that mental health issues didn’t exist for him. This would often leave Dottery with pent-up anger, leaving him in a difficult emotional space.

Dottery has also had to come to terms with the intergenerational trauma he carries as a Black person in America.

According to the American Psychological Association Dictionary intergenerational trauma can be defined as: “a phenomenon in which the descendants of a person who has experienced a terrifying event show adverse emotional and behavioral reactions to the event that are similar to those of the person himself or herself. These reactions vary by generation but often include shame, increased anxiety and guilt…”

Dottery has dealt with this intergenerational trauma but has also been able to look at it through a positive lens. That there’s a certain power that comes with the persistence in his existence and taking care of himself.

“Although we do have the trauma that came with slavery. I feel like there’s also this big sense of power,” Dottery said. “We overcame all of this. We’ve overcome all sorts of oppression. We just prove every day that we prove to white people every day and everybody who’s ever thought that we were anything but bigger than them that we can be better.”

Breaking generational curses and healing for himself has transformed Dottery for the better.

“It just feels like walls are coming down,” Dottery said.

Arriving at CHS and immersing himself in new spaces has led to Dottery changing his perspective on mental health. After reading and giving a new outlook a try, Dottery has made his mental health a priority to heal all that he had pent up for so many years.

On Saturdays, Dottery can be found giving himself a facial, listening to an inspirational sermon or taking time to give himself back what was stripped from him over the week. He performs this ritual of love every week.

He calls this day: The Sabbath.

Dottery believes the best way to move forward is with words.

“You can only start a discussion, that’s all you can do,” Dottery said. “If you open a space where that discussion can be had, that’s the first step.”

An additional community with a stigma around the topic of mental health is the refugee community.

The criteria of arrival to come to this country as a refugee is to have experienced disaster, chaos, persecution, or in other words a form of intense trauma. To be a refugee stems from traumatic experiences, to identify as a refugee is to carry the weight of your, often intense, experiences.

Dr. Odessa Gonzalez Benson, assistant professor at school of social work at the University of Michigan, describes the close intertwinement of the experience of trauma and the identity of a refugee. She works with organizations run by refugees and helps them by using leadership development and training and organizational development.

She recognizes the difference in perspective when it comes to mental health and how, when immersed in a new environment, it’s not smooth nor simple to recognize a whole new perspective of a struggle we all go through.

The U.S. looks at mental health through the lens of a “medical model,” which is a set criteria that looks at mental health like a diagnosis or disorder, rather than a personal condition that’s individual and different for everyone.

“The medical model has not really been applied to refugees,” Dr. Benson said. “They have to transition to a medical model, which gets resistance because of cultural, historical and ideological differences.”

There are many barriers including cultural, linguistic barriers and lack of representation that prevent refugees from being able to relate to this model. This model is ingrained in the western world but foreign to some other places around the world.

The difference in viewing mental health is quite different in the west, specifically the U.S., than other places. In the U.S., it is individualized and one-on-one.

“In many refugee communities [mental health treatment] is very community based and spirituality based,” Benson said. “Here it’s usually about psychology and cognitive behavior therapy and asking the individual. Being one-on-one, it’s up to the individual to fix their problems versus refugees who lean more on their peers, family and community.”

The transition of perspective and barriers results in more hesitation within the community when wanting to seek help. Taking it upon themselves is a more common and familiar practice.

But when arriving in this country, the main concern isn’t how well the adjustment is going. When refugees arrive in this country, success isn’t measured by the amount of healing but by the contribution to the economy.

There are added pressures of assimilation and conformity to American culture and society upon arrival. It also forces us to look at mental health in a completely different and extremely foreign standpoint.

“It becomes more complicated when mental health is intersected with cultural, ethnic and expertital differences,” Dr. Benson said.

The resources this country provides are resources based on the familiarity of the western medical model, which is foreign and unfamiliar to many.

Healing and moving forward includes supporting these communities even when an approach to mental health seems foreign. To not intervene, but to ask what is needed.

“My approach is to help refugees help their own organizations not to help build my own or intervention,”

Dr. Benson said. “So I usually just build on what they’re thinking, what they’re planning to do in various programs. The approach is to be participatory and to prioritize their ways and knowledge that they bring rather than to start from the western approach.”

Dottery truly believes this generation is breaking barriers in regards to mental health and that our progression is monumental and astounding.

“We’re the generation [of] change,” Dottery said.“It’s just nice to know that this generation, we’re definitely more open about mental health and we’re all going through it together.”