Past to Future

Who am I in relation to my past? I am still learning about how my ancestors, and their experience, inform the life that I live today.

“I don’t love you anymore.”

This is what my great-grandmother said to my grandfather to convince him to leave his home, to keep him safe. This is the experience that my grandfather passed down to my father, which influenced the way he thinks of love. This is my family history, what my DNA remembers.

When he was eight years old, in 1939, my grandfather left Austria on a boat to come to America, accompanied by his thirteen-year-old brother. They left behind their parents, who weren’t able to get visas, and their community to travel to a country they had never been to before because their world wasn’t safe anymore. They were Jewish, and in the midst of World War II and Nazism in Europe, they were forced to leave. They didn’t see their parents, my great-grandparents, again.

I never heard this story from my grandfather, even though he was the one who lived it. He refused to talk about his life in Austria and he never spoke German again. What my father knows, he learned second-hand, from his relatives. When my grandfather died in 2016 he left many more questions than answers behind him.

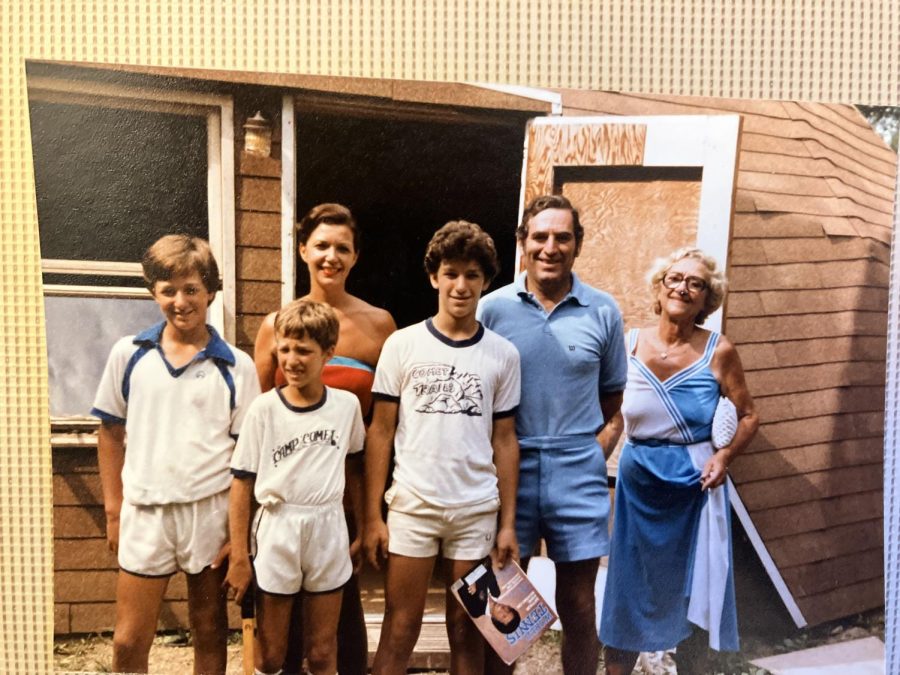

My grandfather was not a kind person to grow up with. He was tough, my father says, he would get angry quickly and unexpectedly. I hardly knew him, because my father was so affected by the way he parented. I think that this has influenced how my father parents me and my siblings. When my father gets angry, he tells us that we are lucky to grow up with a father like him, not like my grandfather. He does not talk about his feelings because he thinks we do not want to know. In truth, he wanted to know his own father’s feelings, but was never granted access. It is a cycle, and we are continuing it.

I cannot truly understand how growing up in a household with my grandfather affected my father emotionally, but I do know that on a biological level, his brain chemistry, and mine, is different from others. In a study done by Scientific American, descendants of Holocaust survivors are shown to have different stress hormone profiles that prevent them from dealing with trauma as proficiently as their counterparts. My father is one of these descendants. I am one, and my brothers and sister are, and all five of us have diagnosed anxiety disorders.

I spend a lot of time considering what-ifs. What if my great-grandparents had come to America with my grandfather? What if my grandfather had talked to my father about his experiences and shared his trauma? Would my father now know how to deal with his own anxiety and communicate his own feelings? And on the other hand, what if my grandfather had never come to America? Would he have survived the war? Would I exist? Would I be a completely different person?

I can’t answer these questions, and I will never be able to. But I can start to heal the cycle, and piece together what has happened to the rest of my family. Recently, we found letters from my great-grandparents to my grandfather dated 1942-1944, right before they were interned in Auschwitz. Translating and reading them together has helped me feel more connected to a family I would otherwise have no link with.

I am still learning about my family — writing this article, I discovered that my grandfather had two brothers, one that died before he came to America. Now, my father and I are working to become Austrian citizens together, in an effort to know more about this side of our ancestry and about each other. We have spent hours filling out forms and getting fingerprinted in hopes for an Austrian passport.

My grandfather never returned to Austria. His brother did, visiting the place they grew up, the school they went to, the parks they played in. But my grandfather never had that closure, that cathartic moment of return. Maybe instead, my father and I will take that journey and, in doing so, take a step towards healing the cycle.