Learning Through Loss

Becky Brent’s father showed his first signs of illness in the midst of a wedding ceremony, his speech becoming slurred, his steps stumbling. Fearing a stroke, Brent’s family took him to the hospital, where he was soon administered a brain scan.

“[The doctors] came back within 15 minutes and told us he had a tumor in his brain,” Brent said.

Her father had his first appointment with the neurologist a few days later—the tumor had already doubled in size.

“By the time we got to that first appointment he had already lost his ability to complete full sentences,” Brent said. It had only been a few days since his initial diagnosis. In the face of the cancer’s rapid onset, her father made the choice not to pursue treatment.

“[It’s] the interesting thing about feelings, [that] you can be feeling multiple feelings at one time, all at different levels of intensity,” said Brent, choking up. “I was angry. I was really angry at the entire situation. I was sad that we had no control.” She half-smiled. “I respect my dad so much and respect his decisions so much that I respected his decision even though it was hard for me. Even though I probably wouldn’t have chosen that for myself. Or for him.”

Just six weeks after his first symptoms, her father passed away from glioblastoma—a hyper-aggressive brain cancer.

In the three weeks before his death, Brent moved in with her mother to help care for him.

“I felt I was able to give him all of myself in his greatest time of need—like he had done for me so many times as I grew up,” Brent said. She and her mother remained with him until his last breath.

“Let me tell you,” Brent said. “I pulled on all of my wellness tools, all of my studies, all of my decades of experience [to cope with this].” She took three months unpaid family medical leave to make sense of what had happened.

“So many things at that time just became so clear to me,” Brent said. “So many of the things I was wasting my time worrying about—I decided I never wanted to waste time like that again.”

She started reorganizing her personal life, then reorganizing her physical belongings, removing all the extraneous things in her life—all the things that had stopped bringing her joy.

“It felt really cathartic to go from space to space in our home and just say, ‘You know what? This isn’t happiness for us anymore,’” Brent said.

She helped her mother clean house too, sorting through her father’s items, making funeral arrangements and talking it all through together.

“It took our relationship to a whole new level, where it’s almost not like mother and daughter, it’s almost more like soul to soul,” Brent said. She refocused on her family, playing with her kids, and with her dog, but healing wasn’t always collaborative for Brent.

“There were days that I didn’t really feel like doing any of that,” Brent said. “I didn’t feel like going out, I didn’t feel like seeing anybody, or talking to anybody, or even answering a text message.” She recognized that she needed to allow herself the same space to grieve that she allowed those around her.

“When I was ready to come back to those messages or those phone calls, the first thing out of my mouth was ‘Thank you for giving me the space to grieve, I needed that. But I’m ready now,’” Brent said.

It was the last lesson that her father taught her: you deserve to put your own needs first sometimes.

“[He] complained about his job all the time,” Brent said. “Like hated it: hated the commute, hated the disrespect from his bosses, hated wearing a suit, just all of it.” He passed away just two years into his retirement, after years of putting himself second to provide for his family. She realized that she couldn’t waste her time at an unfulfilling job.

“When the wind blows, I sometimes get this notion that it’s him tapping me on the shoulder in a way,” Brent said.

The opportunity to change paths presented itself when her friend Robbie Stapleton, a former CHS health teacher, made the decision to work part-time, leaving an opening at CHS.

When Brent walked into her interview, she knew that this story was the one she had to tell—the loss of her father was the acting force behind her career transition. When she was offered the position, she took it.

“I don’t think the [healing] process ever ends,” Brent said.

There won’t ever be a time when she stops thinking about him, or being reminded of him, but the intensity of the emotion has dulled.

“I can talk openly about it, usually without crying,” Brent said ruefully. “Though sometimes I still tear up.”

Though she mourns what she’s lost, it doesn’t always have to feel as painful.

“I feel like what I’ve learned outweighs the grief of the loss,” Brent said. “And I always feel like he’s still kind of with me, you know? It’s strange—it’s strange, but I feel like he’s still kind of here.”

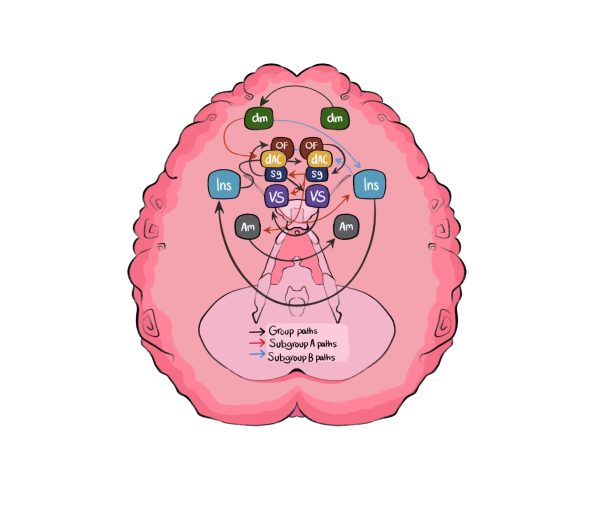

![[Caption]. [] by [Graphic by Sarah Fay] is licensed under [CC BY-NC-].](https://chscommunicator.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/mentalhealth_image-600x450.webp)