Chronic Illness Isn’t (a) Uniform

It isn’t always seen, like a navy blazer, and its impact changes from person to person.

When Clare Martin-Schwarze, CHS junior, was diagnosed with amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome (AMPS), she was relieved.

It had been four months since her symptoms first started. She was woken up one morning by a stinging pain in her shoulder. She initially brushed it off, hoping she had just slept funny. But the pain didn’t go away – it spread.

During the fall of 2021, Martin-Schwarze’s discomfort progressively worsened. By December, Martin-Schwarze was in constant, excruciating pain. Mundane activities, like playing piano and walking up the stairs, suddenly became agonizing.

Throughout the next three months, Martin-Schwarze was a regular at her doctor’s office. She couldn’t sit through a full day at school: walking through the halls was exhausting and sitting at a desk felt like being stabbed in the back.

A single thought persisted in her mind: ‘What is happening to me?’

“I had two doctors tell me, ‘Well, you’re a growing teenage girl, it’s probably growing pains, it’s not all that serious,’” Martin-Schwarze said. “Both of these doctors were men and I felt written off by them. [Then] I went to a [female] medical professional and she believed me and took me seriously. [It] was this huge wave of relief, just to know I wasn’t crazy.”

After the initial relief, Martin-Schwarze realized with all of the answers her diagnosis provided, new questions arose.

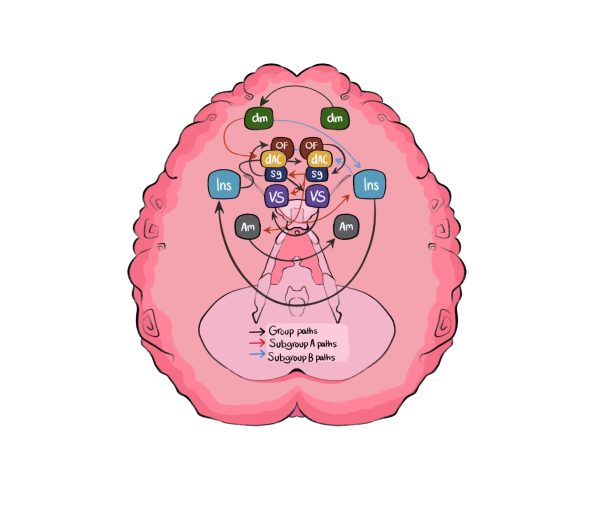

AMPS affects the way the body perceives pain; when registering an uncomfortable movement the pain receptors notify the neurovascular nerves, sending the nerves into overdrive. The nerves constrict and cut off oxygen and blood flow to the bones and muscles, leading to an excess of lactic acid and other waste products. Discovered in the early 2000s, the understanding and treatment of AMPS is still in the early stages. Access to inpatient treatment and specialists is incredibly limited. Luckily for Martin-Schwarze, the University of Michigan has one of the country’s few intensive outpatient facilities.

In May 2022, Martin-Schwarze began to attack AMPS head on. Since Martin-Schwarze’s nervous system perceives normal actions as painful, she must trick it into thinking otherwise. By performing the same uncomfortable movement repeatedly, eventually, her body will no longer register the action as painful.

“[The change has been] night and day,” Martin-Schwarze said. “I was a healthy, typical kid and for the past 10 months, every week I’ve had at least two medical appointments. I’ve seen over 20 doctors; I’ve had MRIs, X-rays, bloodwork and EKGs; I’ve done 22 weeks of physical therapy; I stopped being able to attend school full time. I was very passionate about music. I played piano and violin. I had to quit both [because of] this.”

Martin-Schwarze’s new treatment plan has given her short moments of relief from her constant agony. After an intense exercise session or a particularly successful appointment, Martin-Schwarze’s body is overloaded with stimulus, giving her five glorious minutes of respite. Even as she improves, it’s hard to stay positive.

“The staff kept telling me that after treatment many people find they’re pain-free in five years,” Martin-Schwarze said. “And I was like, ‘That’s college.’ I’m trying to make it through my last month of my sophomore year, I can’t think about five years. It was hard to come to terms with: this could be with me forever. Will I be able to graduate high school? Will I be able to go to college? How will I be able to work a job? It really changed my outlook on my life.”

In 2017, Stacey Simpson Duke, Minister at The First Congregational Church of Ann Arbor, mentioned a marble-sized lump in her upper thigh to her doctor. After an ultrasound and additional imaging, spots were also discovered in her lungs. Duke’s doctor diagnosed her with a fungal cough common in Michigan and Ohio that leaves scar tissue in the lungs and told her to come back in a year to make sure her scans looked the same. When she returned a year later, the spots had grown in size and number and spread to Duke’s liver; the marble-sized mass was a cancerous tumor. A year after her original misdiagnosis, Duke was diagnosed with metastatic leiomyosarcoma.

Leiomyosarcoma is a rare type of cancer that originates in smooth muscle tissue, such as the digestive system and blood vessels. Her cancer was also diagnosed as metastatic, meaning the cancer has spread from the point of origin.

“I was told from the beginning this is not something to be cured,” Duke said. “I think the word incurable is something that can rob people of a sense of hope or agency. But I think that’s because we tend to have [a] kind of black and white thinking, like I need to be a success story. I’ve had so much healing and so many moments of healing, some are physical and some are not. That has been a part of my story over the past five years, there’s not an equal sign between those moments and cure.”

For Duke, many of these healing moments were found in instances where she was not focused on cancer. While much of her life was characterized by her disease, Duke felt it was even more important for the moments of normalcy to reflect who she truly was. Cancer was not her identity — it was merely her diagnosis.

Duke’s blog, “Beyond,” helps her express her thoughts and feelings clearly and allows her to see how far she’s come. Within her online community, Duke found a safe space to relate to others and share her experiences. The posts where she explains the devastating extent of her diagnosis garner the most traction amongst her following; her readers find comfort in her blunt, comprehensive writing.

While Duke leaned on different facets of her identity to remember who she was beyond her illness, she found herself leaning on the people in her life as well. Her husband and two sons grieved, processed and healed alongside her. Her faith has also served as a pillar to lean on.

“My faith was not the kind of faith where if something bad happened, it called everything into question,” Duke said. “I know a lot of people, once they have a diagnosis it shakes everything up. And they aren’t sure if they still believe in God or [think] how could God let this happen? My faith has always been a resource when dealing with bad or good things.”

Sarah Fraley has been a social worker for the last 30 years; she specializes in chronic illnesses and helps patients make the lifestyle adaptations that become necessary with their diagnosis.The new changes that come with a diagnosis can feel just as overwhelming as the presence of an illness. Patients are often met with new challenges; changes in mood and behavior.

“For instance, somebody who is diagnosed with diabetes, [is] confronted with: now you need to eat differently and now you need to take insulin, or maybe you need to be more active,” Fraley said. “There’s lots of lifestyle and medical things that people now need to do. So, behavior has to change.”

For many patients, a change in lifestyle requires some level of loss in their life — loss of activity, nutrition, control — often prompting a grieving period. During this period, while care is administered to the patient’s physical health, their emotional and mental health is often overlooked.

“As someone’s diagnosed, they often don’t get the follow up,” Fraley said. “I really believe in a holistic approach where you’re looking at, how is this affecting your mental health? How is this affecting your physical health? What are the lifestyle changes? Getting the support of someone in the mental health field can be really beneficial and helpful.”

Mental health providers are an integral part of comprehensive post-diagnosis medical care, often providing life-changing advice for those living with chronic illnesses. However, the number of social workers who specialize in chronic illnesses is incredibly small.

“My profile says ‘chronic illness,’ but you don’t see that in a lot of people’s [profiles],” Fraley said. “But there are people out there. If I [don’t] have space, I maybe know somebody else who does. So I think getting that support is super important. It can be really helpful.”

Fraley encourages people to take care in their phrasing when discussing chronic illness, and to be cognizant of the fact that not all illnesses can be seen.

Duke has found healing in her honesty about her illness; being able to be open about her struggles, failures and hardships has given her an outlet to process her diagnosis. (she) is a big proponent of not being consumed by the darkness and dealing with the grief that comes with a chronic illness.

“In our culture, we want things to be positive and people to think positive,” Duke said. “There is such a hardcore belief in our society, that if you just think positive, you can make it all better, you can think positively enough that you can heal yourself. I believe in science; if I thought we could all just decide we’re okay by having a better outlook then that would be unnecessary.”

![[Caption]. [] by [Graphic by Sarah Fay] is licensed under [CC BY-NC-].](https://chscommunicator.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/mentalhealth_image-600x450.webp)