Title IX: History of Fighting and Hopes for the Future – Part 1: Tricia Saunders

This story marks the beginning of a three part series about the history of Title IX in Ann Arbor athletics. Each story will feature a figure in Ann Arbor athletic history and their stories of battles to uphold Title IX values.

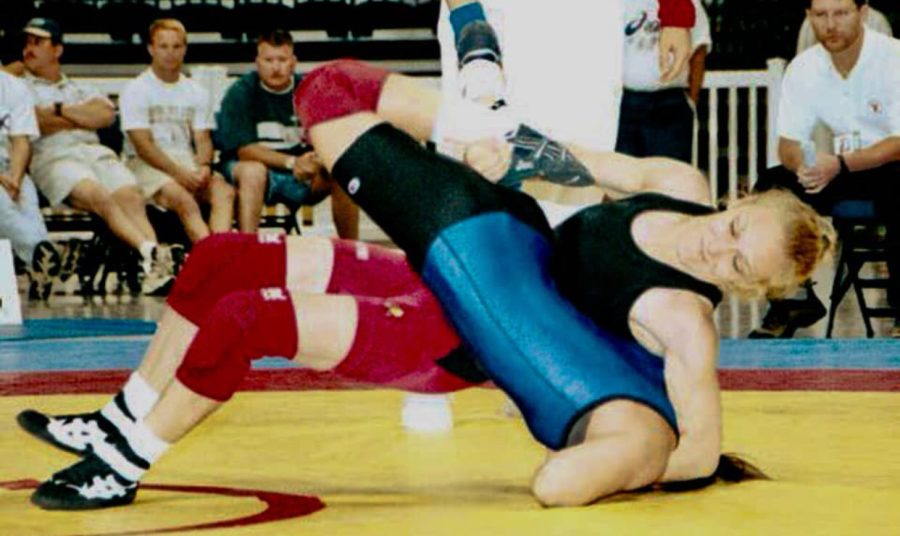

Saunders grapples with an opponent. Saunders grew up learning to wrestle alongside her brothers. “We fought and we got along just like any other pack of kids on a team,” Saunders said.

“I thought I had the right to be there like anybody else.”

That was the message Tricia Saunders told herself. She saw herself as nothing more than an eight-year-old, 45 pound little girl from Ann Arbor who loved wrestling. Unbeknownst to her at the time, she was a figure on the forefront of the battle for the advancement of women in athletics.

Between the moments of hiding from blaring critics behind the limbs of her coaches or sitting in courtrooms between her parents, among the crossfire of battling attorneys, Saunders found little time for focusing on much other than wrestling–it was in her blood.

Saunders grew up among a family of grapplers. Her father, Jim McNaughton, and brothers, Jamie and Andy McNaughton, were wrestlers, and her grandfather was an All-American wrestler at the University of Michigan. In 1971, at the age of seven, Saunders began wrestling at the same club as her brothers.

“I was told since I was little, ‘if you’re good, you can kind of do as you want’ – and I guess I was.” Saunders said. “I liked my peers and they liked me. We fought and we got along just like any other pack of kids on a team. Even though I was the only girl [at the wrestling gym], if I worked as hard and I was winning, I didn’t ever think there was anything wrong with me being around.”

Inside her gym, Saunders was surrounded by support from her teammates and coaches, but as she began to go out and compete in, as well as dominate, meets, she was often met with harassers denigrators.

“People always told me things weren’t possible, but I just did them anyway,” Saunders said. “[There were] cameras and people yelling at me; I just had to block it out. I assumed it was okay for me to be here and that they just didn’t understand that girls can be good at [wrestling]. I didn’t know those people and what they thought was not something that I let enter my space.”

Saunders leaned on the support of her team and the adults around her in order to stay focused on her goal: to win.

In 1975, when Saunders was eight years old, she had qualified for the Ameteur Athletic Union (AAU) youth national championships. She was prepared to travel and compete for the title, but she was informed that she would not be allowed to compete because she was a girl.

“I went to court and my parents fought with a team of attorneys,” Saunders said. “I would have had everything ended for me if Title IX hadn’t been there. I don’t think a lot of people understood exactly what [Title IX] was at that time, so when I won it was a huge statement. I was so young, how much I understood of the world was so limited and I didn’t realize what [this case] meant. All I knew was that I got to go [to the tournament].”

Saunders would go on to have an illustrious youth career. Wrestling against all boys, she obtained a record of 181 wins to a mere 23 losses. In 1976, she became the first woman to win a Michigan state title and the first woman regional national champion as well.

Unfortunately for Saunders, her wrestling career came to a quick halt. As she entered her middle school years at Scarlett Junior High, Saunders was shut out by the coach of the wrestling team and informed that she would not be allowed to be a part of the wrestling program.

“I never got the feeling that he wanted me there.” Saunders said.“He coached my brothers and coached my teammates, but he just never spoke to me or looked at me. He never said anything like he wished I could have wrestled and been on that team. I don’t know if he was part of that decision making or not, but it seemed like he was kind of happy with me not being allowed to compete].”

With little that she could do, Saunders moved on to other sports, but the absence of wrestling did not come without disappointment.

“I felt alone,” Saunders said. “I didn’t know anybody else who had had that experience, so there was nobody to have that conversation with, nobody to talk to about it. I was told ‘you just have to suck it up and move on’; that this is the way it’s going to be and I had to deal with it on my own.”

Saunders went on to participate in many other sports during her youth. She was an avid gymnast and also participated in softball, cheerleading and track during her time at Ann Arbor Huron High School. And yet, there was the lingering feeling of something missing for Saunders.

“I didn’t ever really see those kids, my teammates, again,” Saunders said. “I didn’t ever feel welcome in the wrestling room. Even though I would see my brothers in the wrestling room every once in a while when I was in high school, I remember not being comfortable and wanting to get out of there. I remember thinking ‘this is not your space’”.

It wasn’t until later in her life, after Saunders had graduated from her undergraduate studies at the University of Wisconsin Madison, that the then 22 year-old found her way back to a wrestling mat. She got a call from one of her old club wrestling teammates from her youth, Zeke Jones, who told her about women’s wrestling in the world championships.

“I remember feeling so excited,” Saunders said. “He told me that and I went into the wrestling room the next day because there was something for me. I went to practice every day after that, that’s how it started.”

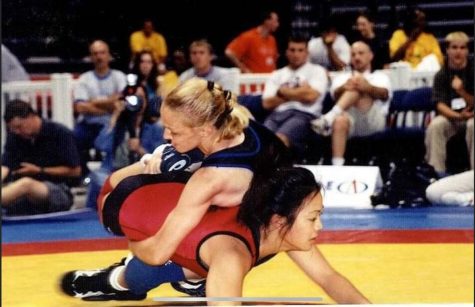

Saunders walked-on to the wrestling program at Arizona State University (ASU), where she was accompanied by Jones, as well as her brother, Andy. She instantly found a connection, similar to the one she had with her youth club, although she was now in a space with individuals who all shared the same competitive attitude as her.

“It just happened to be the number one men’s wrestling team in the nation,” Saunders said. “All of these wrestlers in that room were international caliber and NCAA All-Americans, they weren’t threatened by me. They were already hugely confident in themselves by their own right of everything they earned. They were nice guys that were friends of my brother and they were all really helpful to me and it was a great place to fall into, I felt extremely fortunate.”

However, it seemed like history was bound to repeat itself. While her team atmosphere provided the encouraging and challenging environment that Saunders was looking for, she was followed by the same noise and criticism that she faced in her youth. There was an abundance of coach, referee and even national governing body resistance, trying to cancel Saunders’ program.

“Nothing had changed from the 70s to the early 90s,” Saunders said. “When I stepped outside that room, it was a lot of the same story as when I was a little kid, but I had already learned to keep my chin up and not really pay attention to what anyone says. I had to keep stepping in and never stop showing up even if I wasn’t invited.”

At just 22 years-old, Saunders felt it was her obligation to be a voice for the new generation of women wrestlers in America. She spoke out against criticisms and fought for the rights of women’s wrestlers.

“I had to take the helm, take what my parents did for me and try to do that for my other teammates,” Saunders said. “I fought hard to establish a national team program to make sure that women’s wrestling had a place.”

Saunders reflected back on her experience as an advocate, highlighting the similarities of the various struggles that women have had to establish their place in the world of athletics.

“It’s nearly the exact same story over and over again,” Saunders said. “It makes it almost even more sad, because it’s like you don’t learn from each individual triumph that girls make and they end up having to fight the same battle again.”

The similarities of Saunders’ youth career to her professional one continued to present themselves. While training at ASU, Saunders was working to get a tournament set up so that sha and others could qualify to compete in the world championships. She was contacted by the United States (U.S.) government and was told that they were not going to have a national championship and were not planning on sending a women’s team.

Saunders worked quickly with her companions at ASU and in the professional wrestling community to create a makeshift tournament, allowing her and multiple other women the opportunity to compete for a spot in the world championships, representing the U.S.

Saunders called to attention issues of increased inequity as a result of Title IX. Acknowledging the opportunities that may have been lost for male athletes to make way for opportunities for female athletes.

“Whenever I speak with someone who feels that way, I have to ask: ‘Well, how sad were you when women had no opportunities in sports?’,” Saunders said. “If you only cried for missed opportunities that have happened to men and you didn’t worry at all about any of the mass of missed opportunities that have happened for women in this country, then I don’t think that you’re ready to come to a table for a discussion.”

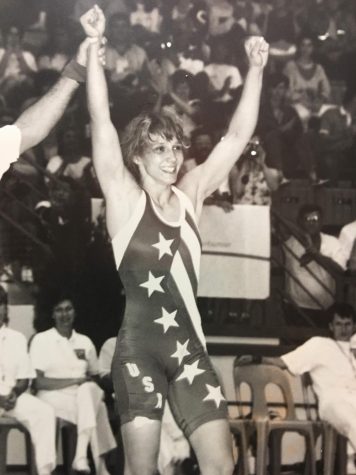

Throughout her competition days, Saunders amassed a large number of accolades such as four FILA Wrestling World Championships gold medals, her first of which crowned her as the first American woman to ever do so. She holds 11 national titles and in 2006, became the first woman to ever become inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. Although she has certainly cemented herself as a top competitor, Saunders hopes she will be remembered as a representation of a standard of inclusion for all sports.

“I don’t want to see anything bad ever happen to men’s or women’s athletics,” Saunders said. “If somebody has less opportunities to participate in an activity, it’s a mutual tragedy. I don’t think any kid shouldn’t have an opportunity to do something that the next kid can.”

Saunders highlighted her admiration for Title IX and the importance it has played in sparking many athletic careers.

“When I see people who maybe did get a boost from Title IX and are going off and doing great things, like I was able to do. it makes me really happy,” Saunders said. “I love watching those boys and girls.”

Saunders has proven to be an example of dedication, action and results. She has inspired a generation of athletes to advance the standards of inclusion in athletics.

“The leaders that these young people are going to become because of their sports experiences, what they’ll have to give back, is amazing,” Saunders said. “It’s a different generation that we’re producing now than before and I can’t wait to see the next steps.”