Shining Light on the Dark

Neurotherapist Dr. Gajar speaks on Seasonal Affective Disorder and her experience as a therapist.

As he sat on his bathroom floor, salt pierced his cheeks and his drums throbbed his head. He realized he needed to reach out to someone. Anyone. He was hopeless.

Ben Stevens* went to his phone and dialed his last resort: his cousin.

He never wanted to admit that he was weak and vulnerable, especially not to his cool, older cousin.

“I sat there barely able to catch my breath,” Stevens said. “I couldn’t even get the words out to describe what I was feeling. I was terrified.”

After being diagnosed with Seasonal Affective Disorder [SAD] at a young age, this was all Stevens knew.

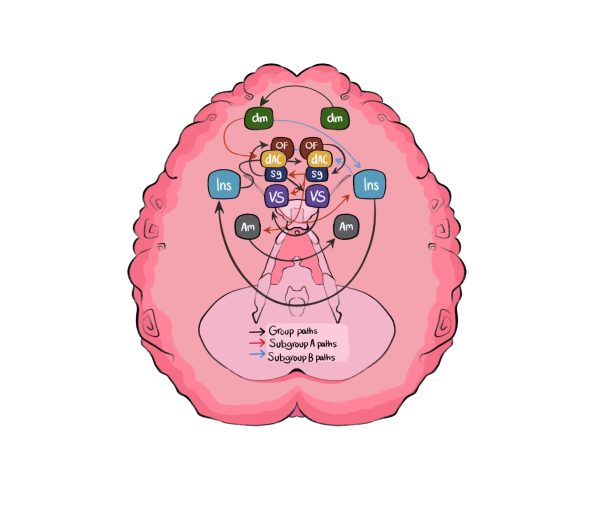

As sunlight becomes less prominent as the calendar progresses, over two million people prepare to face hopelessness, social isolation, fatigue and other symptoms due to an annual, life-threatening condition — SAD. SAD is a seasonal-related type of depression. Its symptoms begin and end at around the same time every year — typically beginning in late fall or early winter and lasting until the sunnier days of spring and summer. It is noticeably less common for people to have the opposite pattern, but still possible. In both cases, symptoms may become more severe as the season progresses: feeling sad or down most of the day; losing interest in once enjoyable activities; having low energy; sleeping too much; having difficulty concentrating; feeling hopeless; or having thoughts of not wanting to live.

Kick-started by her passion for helping others, neurotherapist Dr. Gajar has been treating patients in therapy for two years. She believes the link between the time of year and depression is due to the colder weather and darkness of winter, which she finds correlate with the timing of her patients’ more depressive stages. She has found the same pattern with the ending of the depressive period, with more sunlight and warmth reversing the symptoms.

“Helping others come to the realization that there’s an actual reason for their feelings is what got me into wanting to be a therapist,” Dr. Gajar said. “Just validating [my patients’] feelings along with helping people deal with their trauma is why I love what I do — help others and be that solid support for people who are going through or have gone through bad experiences.”

There are a few signs that trigger to Dr. Gajar that her patient is most likely dealing with SAD. When people start to experience depression, she has them log their feelings, dates and other factors that may trigger their feelings.

“There’s usually that ‘aha’ moment when looking at the timing of the feelings,” Dr. Gajar said. “When I have patients log their feelings, things line up and you can see this pattern and make that connection when dealing with Seasonal Affective Disorder.”

SAD is not a separate condition, but a type of depression. The term “seasonal depression” is often thrown around as an adjective versus the true diagnosis it is. Dr. Gajar believes this is not shared often enough and leads to misconceptions about the condition.

In more recent years, Dr. Gajar finds her patients often self-diagnosing themselves with SAD. She thinks it is valid and understandable because of the lack of resources available to all. Although you may need a diagnosis to help get the proper medication, if what you’re doing feels helpful, Dr. Gajar doesn’t see an issue with self-diagnosis. She thinks that without the self-diagnosis, her patients often invalidate their feelings.

The uncertainty from the COVID-19 pandemic caused more cases of SAD. According to Mental Health America, the number of U.S. adults experiencing depressive symptoms has tripled.

Dr. Gajar’s patients were lacking the assurance of contentment from the spring. Not knowing whether they would still be locked at home in quarantine increased the severity of some SAD cases. The cold, lonely feeling from winter, playing an important role in SAD, didn’t end when people continued to be quarantined.

“I could see my patients finding themselves in what seemed like a never ending tunnel,” Dr. Gajar said. “They weren’t sure if they were going to be able to even leave their houses as the warmer days approached, which made it harder for them to get out of their more depressive stages. They lacked normality and mental security.”

The most common coping mechanism in Dr. Gajar’s office is light therapy. A light therapy box mimics sunlight, causing a chemical change in the brain to ease symptoms of SAD; it can lift your mood, and even help with poor sleeping patterns.

Dr. Gajar also suggests going to therapy.

“I may be a little biased, but I think therapy is so important for everyone,” Dr. Gajar said. “Opening up and talking to people has proven to help with SAD, and mental health in general.”

*Names have been changed to protect anonymity.

![[Caption]. [] by [Graphic by Sarah Fay] is licensed under [CC BY-NC-].](https://chscommunicator.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/mentalhealth_image-600x450.webp)