A New Generation of Learners

After the Covid-19 pandemic, learning has been turned on its head. Technology usage has increased exponentially in classrooms— how is this affecting children’s education?

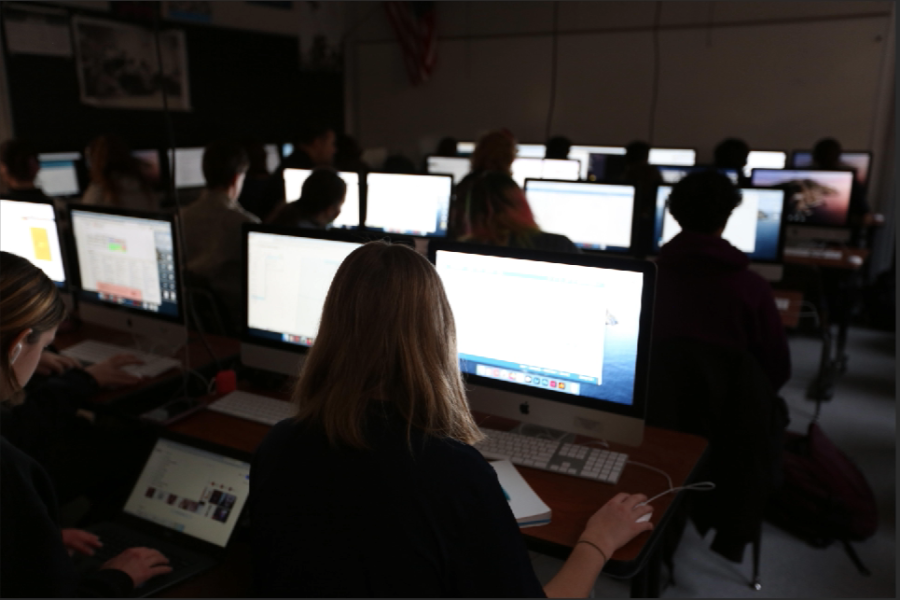

Students work on computers in Engineering, a technology-centric class at CHS. The use of technology has changed since the Covid-19 pandemic and the year of online learning. “The pandemic just made (school) internet factorial,” Kreger said.

Online college applications that can be submitted with a click of a button. Computer programs that facilitate learning fractions and decimals. Writing and editing in Google Docs. From kindergarten to senior year, students use technology in the classroom every single day. How is this different from past generations of learners?

According to Gallup Inc. on behalf of New Schools, 57% of students reported that they used digital tools in class everyday in 2020. Furthermore, 65% of teachers use digital learning tools to teach everyday. The lives of teachers and students are permeated by technology, both in their private lives and in their working and learning environments.

The use of technology within the classroom has changed drastically over the years. According to Rebecca Lee, a sixth grade English Language Arts teacher at Tappan Middle School, the technology has evolved drastically since she began teaching 19 years ago. It started with the overhead projector.

“If we had our own [projector], it was just amazing,” Lee said. “My first classroom had a chalkboard and I remember getting chalk everywhere.”

The next big deal was a projector on a cart, which allowed teachers to connect their computers and use Microsoft PowerPoint to present information. This evolved into document cameras, known as Ladybugs in Ann Arbor Public Schools (AAPS), which revolutionized the way that teachers gave examples. However, they were few and far between.

“We only had one per floor so we would all fight for it, and who was gonna win that battle?” Lee said. “Sometimes you just kind of give up and go back to your overhead projector.”

In the present day, teachers have access to WiFi, Smartboards and online learning platforms like Schoology. According to Lee, this has created both positive and negative outcomes. Having access to technology, both at home and in the classroom, allows students to communicate with their teachers and their peers, as well as view their assignments and autogrades almost immediately.

“Nineteen years ago, we were lucky if a student had a computer at home to email us,” Lee said. “Today, kids can email us in the middle of class. They can email from their phone, they can have their parents email and so it becomes this instant connection if they need it.”

However, the absence of physical assignments has decreased the engagement of students, in Lee’s opinion.

“[Technology] takes away some of the magic that comes with getting the pen marks on your hand and that proud ache in your wrist of writing for 30 minutes and having a complete story in front of you,” Lee said. “It has its own trials and tribulations.”

Sandy Kreger, a fifth grade teacher at Burns Park Elementary School, has noticed this phenomenon in her own students. She describes it as a lack of “struggle” — since students have what seems like unlimited information at their fingertips, they don’t experience as much frustration as past generations. Kreger attributes this in part to the Covid-19 pandemic.

“The pandemic just made [school] internet factorial,” Kreger said. “Everything was done on the computer.”

During AAPS’s year of online schooling, Kreger experienced a decrease in work completed by her students. She worked overtime, staying on Zoom for hours after the school day ended in order to help students that were struggling. In some ways, the pandemic helped Kreger connect more with her students because she was able to see everything her students were doing while they were doing it. Lee echoes this sentiment, describing her appreciation for how Schoology allows her to follow along with her students’ work.

A main fear of an effect of the pandemic is that it will put students behind academically. Kreger doesn’t believe that this is the biggest thing to be worried about. “Everybody was saying, “Are they still behind?’ Kreger said. “I’d say, ‘Behind whom?’The whole world is experiencing this pandemic. Kids are pretty resilient. They can learn these things, they can catch up.”

Instead, Kreger is worried about instant gratification. She reports that during virtual learning, she would hear kids have Youtube or Netflix on in the background. They wouldn’t have to wait for a snack and they wouldn’t have to share with anyone. As the district and the country transition more fully into regular learning, Kreger is concerned about teaching children how to connect and cooperate with one another.

However, Kreger and Lee both have hope for the future of learning. Kreger gives an example of students in her current class, who helped her figure out how to make a flowchart online. They worked together to figure out the different online tools and when Kreger saw that the kids were struggling, she offered to show them how to create it on paper.

“They said, ‘Please, let’s figure it out,’” Kreger said. “It’s exciting to see that they’re wanting to work. It’s much more engaging and colorful and maybe important eventually for their careers in their life [to be able to work online].”