Therapy Through The Screen

Technology’s impacts on therapy: both the good and the bad.

Malevolent monsters, sinister plotlines and apocalyptic events are all what help create modern horror films: These chilling elements are meant to incite fear and trigger one’s ‘fight or flight’ response.

Eve Kaplan, CHS senior, faced countless sleepless nights after watching a scary movie. This reaction was later recognized as her first panic attack. To combat this fear and control her anxiety, Kaplan started seeing a cognitive behavioral therapist whom she has been seeing since seventh grade—before the pandemic. In the very beginning, Kaplan and her therapist played games, colored and discussed more surface-level topics in effort to change her mindset. A common topic in their early sessions regarded the different aspects of life, like physical, social and emotional wellbeing, and how they coincide with one another.

“I’m just working on my mindset and accepting things for how they are,” Kaplan said. “[And] figuring out what I want to be putting the most [of my] energy into and it helps me a lot with being intentional with how I was using my time and energy.”

As people went into isolation during the pandemic, Kaplan continued on her path of self-care and self-awareness. Although it was beneficial to already have such a close connection with her therapist, the road was also not entirely smooth. Adjusting to the new circumstances was unsettling at first. As someone diagnosed with ADHD, it was much easier to get distracted and feel disconnected because of the loss of face-to-face contact.

“It took a little bit to figure out how comfortable we both were,” Kaplan said. “Like, ‘can I be doing this?’ [or] ‘do you care if I’m literally laying down in bed?’”

However, as time went on, the typical therapy session for Kaplan became more casual: sitting comfortably in her bed in sweatpants and with a snack as she talked about her week.

“It can feel more comfortable and kind of freeing if you are in your own safe space [that you] created for yourself at home,” Kaplan said.

For Kaplan, online therapy has transformed her mental health and the pandemic acted as a time of self-discovery. As an introvert, the isolation that the pandemic brought didn’t disrupt Kaplan’s world as much and seeing her therapist every week brought a sense of comfort and consistency.

“It’s obviously really nice to have somebody that every week, [there’s] a safe person to talk to you about whatever happens to be going on,” Kaplan said.

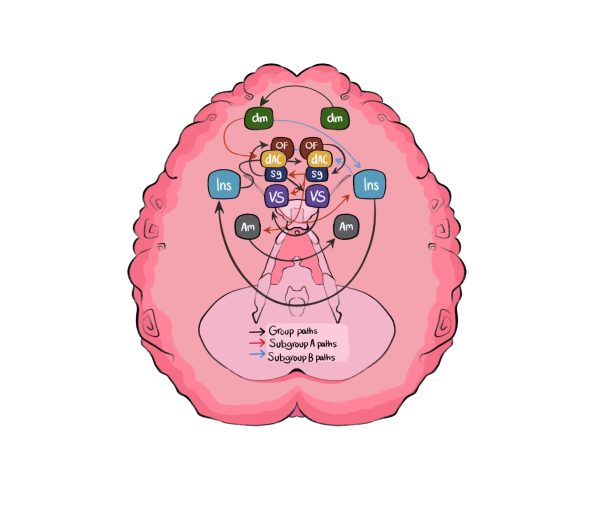

With a particular expertise in understanding how trauma affects and can override the brain, Naomi Zikmund-Fisher, who has been a therapist for nine and a half years, follows a philosophy rooted in the belief that everyone is capable of healing. People often don’t realize that the brain is interconnected: all parts of the brain are communicating with one another constantly.

“What we’re trying to do in therapy is basically unlock [the] innate capacity and get all that good-feeling stuff that’s inside all of us to connect with the trauma that we have,” Zikmund-Fisher said.

Certified in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), Zikmund-Fisher uses a form of psychotherapy that is designed to alleviate the fear coming from traumatic experiences, fixed on the understanding that everyone has adaptive information: memories which are processed and stored in the brain. But to first understand this model’s effectiveness, there are two vital pieces of information to know: what is trauma and why are thinking patterns, resulting from trauma, difficult to stop?

“We can think about trauma as [having] experiences that [have] been incompletely processed and improperly stored in our brain,” Zikmund-Fisher said. “[Our brains] are very defended against really examining them, like we can’t really face it.”

The second piece of information is understanding that the more a person does something, over and over again in the same way, our brains become extremely efficient at it. An example Zikmund-Fisher uses is someone who is afraid to drive a car after a car accident and how their brain processes that experience, evolving into a toxic thought pattern.

“I see a car, I feel fear, I see a car, I feel fear, I see a car, I feel fear,” said Zikmund-Fisher. “Eventually, my brain goes ‘Oh, those things go together,’ and now it’s incredibly efficient. It’s incredibly difficult to interrupt.”

A traditional EMDR session begins with the therapist knee-to-knee with the patient, moving their fingers back and forth while asking questions which initiates the person to think about the trauma as the brain is distracted slightly. Slowly, the person begins to question whether their fear is rooted in reality, making progress to rewiring that brain connection.

Highly effective among Zikmund-Fisher’s patients, she believed that in order for EMDR to continue its efficiency, it could only be in-person. However, as people went into isolation as the pandemic progressed, other EMDR therapists began to brainstorm alternatives. For Zikmund-Fisher, a tool called “Bilateralsimulation.io,” a website designed for therapists to use online.

“We’d have you tile your screen so you can see me and the ball but the window that has the ball goes all the way across your screen,” Zikmund-Fisher said. “From my end, I control it [and the speed].”

Very similar to how EMDR is traditionally, Zikmund-Fisher asks the patient to envision the worst part of the trauma, following with questions like ‘And when you see that picture and you remember what happened, what does that make you believe about yourself?’ and ‘What’s the negative, irrational belief that it makes you have about yourself?’ As the patient repeats this process, Zikmund-Fisher finishes with ‘Where has your mind gone now?’ and feelings of remoteness and distance are prevalent among patients: results of adaptive information.

“[What] we’re doing is trying to move it from something that feels really current and present, and has all the emotions that go with them ,to something that feels like it’s in the past,” Zikmund-Fisher said.

While Zikmund-Fisher has become adapted to EMDR online, she believes that therapy requires trust and good communication, something difficult to build online. But on the other hand, Zikmund-Fisher has started to see more patients online —⅔ of her patients— due to convenience for herself and patients.

“It is really nice to be able to sort of roll out of bed and [get] my coffee and go see somebody, I don’t have to commute,” Zikmund-Fisher said. ”[It makes] life easier just to be able to work from home.”

And while comfort is important for both the therapist and patient, online therapy does not come without its liabilities. In such a technological age, some are not tech savvy or don’t have a device to do therapy, making it infeasible. And issues of commitment and boundaries are not to go ignored.

“[There] are people who want to cook dinner while they’re having therapy, where they want to drive their car or they get up and they walk around, and they do things that you would never do at your therapist’s office,” Zikmund-Fisher said. “I try and educate people like ‘look, when you sit in my office, we have a space, right?’. There’s a physical space, but there’s also a metaphorical space. It’s like this relationship between us. When we’re online, we don’t have the physical space but we still have to have the metaphorical space.”

While there is no physical space for Zikmund-Fisher and her patient, she believes that privacy is another aspect of online therapy that can be easily violated and something people may not realize how important it may be.

“I’ve had people say, ‘Oh, it’s fine, it’s fine, he’s just gonna sit here, he’s not really listening,’ and I’m like, ‘No, it’s not fine,’” said Zikmund-Fisher.

For those Zikmund-Fisher had been seeing before the pandemic, their relationship became stronger as they made the transition to online together.

Through thick and thin, humans are capable of adapting and healing, including using technology to continue one’s self-care journey during an unknown process during an uncertain time, as they made the transition to online together. However, this only strengthened Zikmund-Fisher’s relationship with her patients.

“There was a sense of ‘Okay, you know what, I’m in a pandemic, you’re in a pandemic, we’re doing this together,’” Zikmund-Fisher said. “‘You know, we’re going to figure this out together.’”

It goes without saying that for Zikmund-Fisher, in-person therapy for beginners is the best for both the patient and therapist, making it difficult to diminish the importance of a metaphorical and physical space that in-person therapy has.

“Like ‘here’s our sacred time that we’re going to spend together and we’re only going to focus on each other,’” said Zikmund-Fisher. “[I] think it’s easy to take that for granted or to think that it doesn’t matter all that much.”

Zikmund-Fisher believes that whatever a person can do to fit therapy into their personal life are the first steps to creating a better life.

“Therapy is better than no therapy,” said Zikmund-Fisher.

Carissa Wilder, a therapist in Ann Arbor has been in the field of therapy for 21 years. She has found that since COVID-19 and the ‘big boom’ of online therapy clients have had an easier and more accessible experience with finding therapy and being able to have sessions, given that she has chosen to stay online despite being able to be in-person once more.

Not only has the commute issue of therapy been resolved for Wiler’s clients, but now people seeking therapy are able to open up in the comfort of their own home. This has not only improved the impact on the Earth that traveling has, it has improved the quality of communication in therapy. “I feel like they feel more relaxed,” Wilder said, “Many times, which is a really important component for communication, inhaling like not feeling tense, judged or overwhelmed by surroundings.”. The safe harbor of home for many has now been turned into a place of mindfulness and healing.

One of the major and most surprising perks for Wilder has been being able to see her clients’ pets.

“I really love that their animals are often with them… Many people do have pets and I have a pet too. So it just feels like for a lot of us our pets are very comforting,” Wilder said.“And whether they’re officially emotional support animals or not. They often have the same effect. Of being very regulating for our nervous systems.”

Wilder has loved seeing the new and innovative ways that Covid has forced therapy to become.

COVID-19 has changed a lot in the therapy community, one of the most noticeable changes for Wilder is its move towards creativity in art and nature.

“[Covid] just opened up this idea that there just doesn’t have to be the strict adherence to like being in an office and like having the session be a certain time like that just seems to be a lot more creativity taking place… but I think the pandemics made that even more pressing and obvious that the field needs to adapt and be more creative,” Wilder said.

Moving forward in therapy Wilder hopes to see the field continue to grow from COVID-19 and use it as an opportunity to change into being a more accessible and better place to be.

![[Caption]. [] by [Graphic by Sarah Fay] is licensed under [CC BY-NC-].](https://chscommunicator.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/mentalhealth_image-600x450.webp)