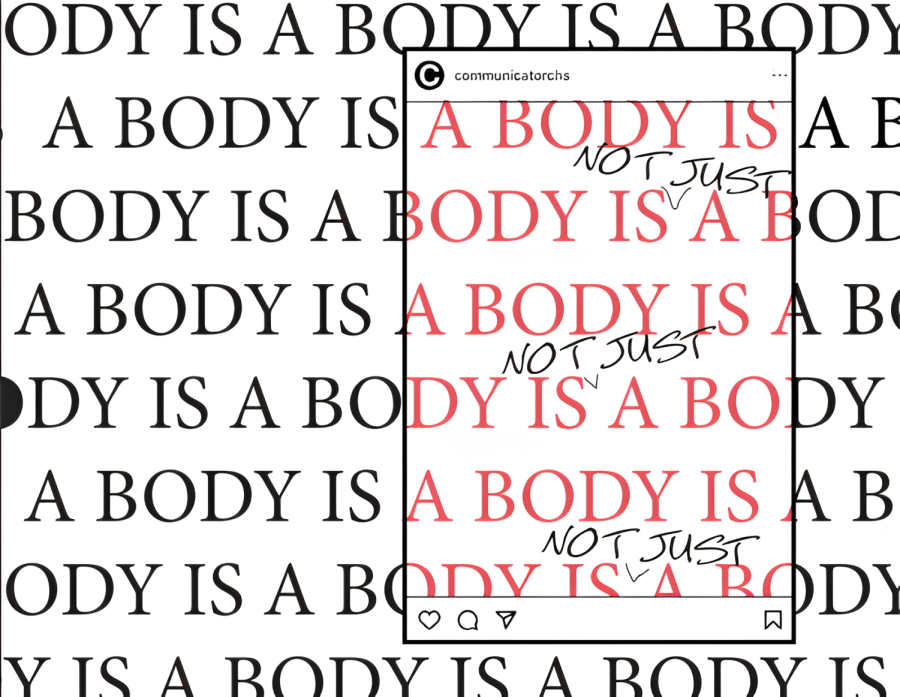

A Body is a Body is a Body

Social media has provided an arena for competing beauty standards, exaggerating the value we place in our own bodies and creating highly comparative situations that can cause the development of bodily insecurities.

Growing up surrounded by her own reflection, the countless hours spent examining herself in the mirror at her dance studio have left Lila Ryan, CHS senior, hyper-aware of her own body. As she entered her freshman year of high school, her time spent in the studio increased. At the same time, her physical appearance was changing. She witnessed her growth frame by frame in the mirrored walls.

“I was 14 years old,” Ryan said. “It was natural, but it felt unnatural.”

She struggled to reconcile with her mature body while she still saw herself in the smaller body from her childhood. As she grappled with the disconnect between her old body and the new, she was also spending more time exposed to social media and the beauty standards that came with it.

Ryan has been involved with social media since she was in fourth grade, beginning with Musical.ly in 2014, which she used mainly to make funny videos with her friends. As she aged, her use of social media changed.

In seventh grade, she downloaded Instagram.

She was suddenly surrounded by more bodies than just her own. As she continued to use the app, her social network expanded and more and more bodies filled her feed.

“It’s always a comparison,” Ryan said. For her, it was always a ‘not’: not as pretty, not as thin, not as popular.

People have a natural tendency to attempt to portray themselves as positively as possible. This self-presentation varies depending upon the target audience. In a work setting, one might want to be perceived as organized and competent, but in a social setting one might rather be seen as easygoing and personable. Attractiveness is a key aspect of presentation: Do other people like the way you look?

“The desire to present yourself in a positive light is very natural,” said Nicole Ellison, a professor in the School of Information at the University of Michigan. Her work focuses on how new information and technologies affect existing social processes.

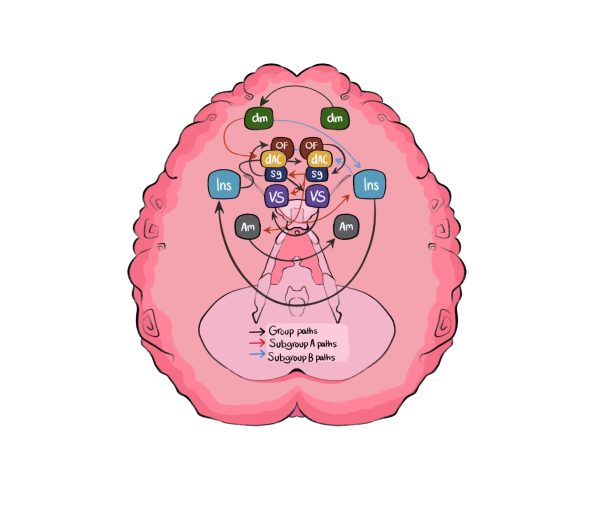

Social comparison dynamics (conscious or not) are present in every aspect of our lives: who makes more money, who scored higher on the math test, who had a more exciting weekend. In computer-mediated communication (i.e. social media), these dynamics can become more exaggerated. Individuals have far more control over their self-presentation in these settings, in which others can only see what they elect to share about themselves.

“When we’re looking at social media, we tend to see more of this curated self that others are sharing of themselves,” Ellison said. “Everyone is sharing the highlight reel.”

In reality, individuals can, for the most part, be seen in all their forms—from just-rolled-out-of-bed to done up in formal attire. Alternatively, social media content can be edited, revised and even deleted. Individuals can only be seen in the states that they choose to publicize.

“You can take 100 pictures and pick the best one,” Ellison said. “You can really selectively decide what you want to share about yourself.”

The result is a plethora of popular social media platforms that grant individuals full control over their appearance to the viewer and therefore platforms that are full of people looking their best—adhering to whatever beauty standards apply to their demographic.

“What I see as attractive is probably what my peer group sees as attractive,” Ellison said. Although there are a wide range of appearance-based standards, there are also certain blanket beauty standards that are associated with given cultures.

In addition to the onslaught of content demonstrating every individual in your network’s best foot forward are highly quantifiable forms of feedback: likes, reposts, comments. In face-to-face interactions, feedback is much more qualitative and thus harder to directly compare. A number of likes to a number of likes makes for a very clear cut means of direct comparison.

Seeing the best versions of other people constantly was overwhelming and added to the insecurity that Ryan already experienced from feeling as though she didn’t have the classic “dancer’s body.” She also began to notice patterns in which personalities were pandered to social media users: the body types that were always showing up on her TikTok For You page and Instagram Discover page.

“You look at the people who are popular on TikTok and they all look the same,” Ryan said. “They’re all pretty and skinny.”

The torrent of algorithmic beauty led Ryan to have unrealistic standards for herself. She lost herself in a pit of weight loss apps and skipped meals.

“I was so hungry, all the time,” Ryan said. The constant comparisons brought her to a place she didn’t want to be. With time—and concerted effort—she has come to realize that constantly comparing yourself to others is unhealthy and unsustainable.

Different people are affected by their exposure to social media in different ways. Not every social comparison has a negative consequence and not every comparison is of any consequence at all.

“Social comparison is not just that you’re comparing yourself to people who are better than you,” Ellison said. “It also could be that you’re comparing yourself to others and end up feeling pretty good about yourself.”

However, many young women have shared Ryan’s experience. Many studies demonstrate that—particularly for adolescent girls—the social comparison dynamics created by social media can be highly problematic.

“You can’t automatically compare yourself to everyone you see,” Ryan said. Now, she can look in the mirror and accept her body for what it is: a body.

![[Caption]. [] by [Graphic by Sarah Fay] is licensed under [CC BY-NC-].](https://chscommunicator.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/mentalhealth_image-600x450.webp)