A New Chapter for Brick and Mortar

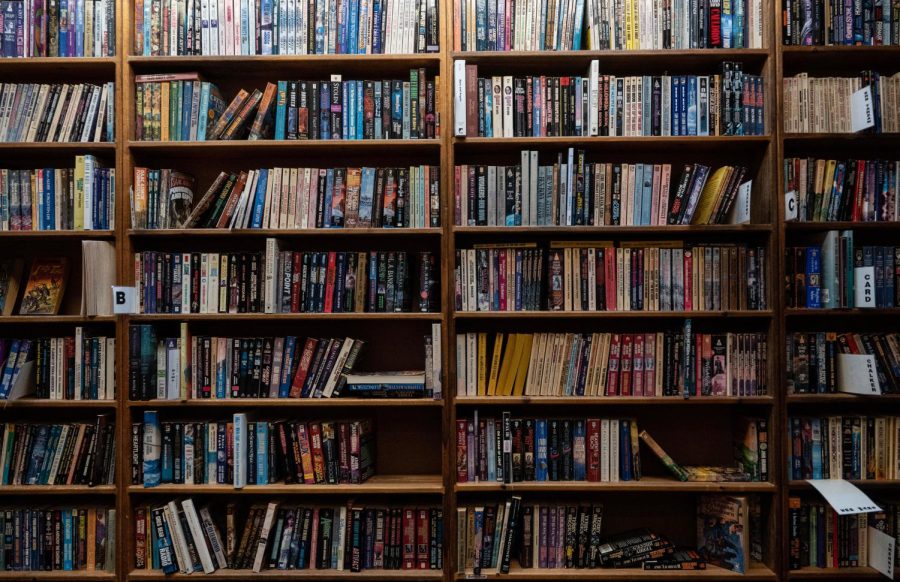

Since the 19th century, Ann Arbor has been known as a book town. It started in 1886, when the town opened its first “reading room;” a place for people to find and read books for free in a comfortable setting. From the used bookstores scattered throughout the downtown area to the well-known local stores like Literati, Ann Arbor is a safe haven for readers of all kinds.

For decades, bookstores have thrived in Ann Arbor, with nine independent bookstores. However, these bookstores have fluctuated over the years — Wahr’s Bookstore, the longest lasting bookstore in Ann Arbor’s history, closed in the 1970s, and Borders Book Shop, the legendary chain born in Ann Arbor, was lost in 2011. As technology increases in strength and reach, many customers are turning to online shopping, including for books. Where does this leave Ann Arbor’s local bookstores?

When Mike and Hilary Gustafson heard that the Borders in downtown Ann Arbor had closed, they were aghast. They knew Ann Arbor’s downtown wouldn’t be the same without an independent bookstore, so they moved back to their hometown from where they were living in Brooklyn and began planning. Literati Bookstore opened two years later, in 2013. Mike Gustafson has noticed a difference in the amount of online shopping since they opened their doors; he recognizes the convenience of it, which appeals to him as well as to his customers. However, Gustafson knows that shopping at an independent bookstore is a completely different experience from online shopping.

“We pride ourselves on a different shopping experience — in-person, with real people, real books, real recommendations, and real customer service,” Gustafson said. “We are always affected by change and the Internet; at the same time, we just can’t compete or change how consumers buy their products. We can only focus on what we love doing, which is helping people find books they love.”

Gustafson believes that the independence of local bookstores sets them apart from other bookstores; they have the ability to choose what titles they stock and what else they sell. Local bookstores are unique in that each one is different, according to Gustafson.

When you have something independent like [a local bookstore], customers can come and surprise themselves,” Gustafson said. “They can find voices and books they never would have found online, things that interest them that they didn’t even know would. Reading is a very special process, an insular and personal one, and I don’t think we should allow algorithms to determine what we read.”

Marci Harris, a CHS French teacher and an avid reader, also recognizes the individuality and specialness of independent bookstores; she recalls fond memories of date nights with her husband, where they would spend hours roaming the shelves of Borders downtown. There are also features of local bookstores that just aren’t present when shopping online or at a corporate bookstore.

“My favorite thing about [Ann Arbor bookstores] are the staff favorites,” Harris said. “I used to always love when a staff would recommend a book and [I could read] what they thought about the books.”

Buying books can be an experience in and of itself, according to CHS senior Zoe Simmons, who has loved reading since she was young. Online shopping takes away from time spent out and about, meeting new people and picking out the perfect book.

“I feel like [online book buying] taking a lot of the experience out of book buying because you can just press a button and buy the book instead of roaming around the store for hours, listening to the music that the bookstore is playing and running your fingers through the books, figuring out which ones you want to read,” Simmons said.

A major component of the online bookselling game is Amazon, which both sells and publishes books. About ten percent of Amazon’s worldwide revenue comes from book sales, which corresponds to $28 billion. Amazon loses money when they sell books; books are priced much lower than the price they usually sell at. Amazon employs the same strategy for shipping — by not charging for shipping, more consumers buy from Amazon. This attracts more customers to their general platform, which is possible due to the monopoly they have over the bookselling industry. However, Gustafson does not see these slashed prices as truly being cheaper than independent bookstores. When Amazon sells books at a loss, it takes money away from authors as well as local bookstores and it influences the kinds of books being published.

“I wish more people would ask the question: ‘Okay, so this is a cheap book. Why is it so cheap? What is the net effect of this?’’ Gustafson said.

Amazon and other online bookstores often have a much wider range of titles than independent bookstores, in addition to their cheap prices and convenience. This can be enough to convince even lovers of local bookstores to turn, in some ways, to Amazon. Harris switched to a Kindle eight years ago — she can take it anywhere, she can look up words when she doesn’t understand them and she can change the font size. There are many reasons for customers to lean on online shopping, and it is difficult for independent bookstores to compete.

However, Gustafson has hope for the future of local bookstores. Throughout the years of Literati, Gustafson has noticed more and more members of the younger generation coming into the bookstore. This is evident in Simmons, who can spend hours in a bookstore and aims to read for five hours every week.

“I’m excited about the future because the younger generation seems to “get it;” they get the value of independent bookstores and independent retail, and they realize the inherent risks companies like Amazon can pose to communities,” Gustafson said. “Watching younger people come into the bookstore has been a wonderful thing to see.”