High-Speed Railways in America and Climate Change

The wheels clanked as they rolled over the tracks. I adjusted in my seat, stretching out the sore spots from sleeping in the train seat the night before. I took advantage of the leg room significantly larger than a plane’s. We had just entered the state of Pennsylvania, riding next to Lake Erie. The 19-hour trip was only about halfway over, and the toilets in our coach were already a mess. We sat for what felt like an eternity on a bend in the track at Schenectady—before we even got to the station. By the time we reached New York City, it was already dark, and the train was about two hours late. It was a stark contrast between the speedy, clean and modern Intercity Express (ICE) we had ridden years before in Germany.

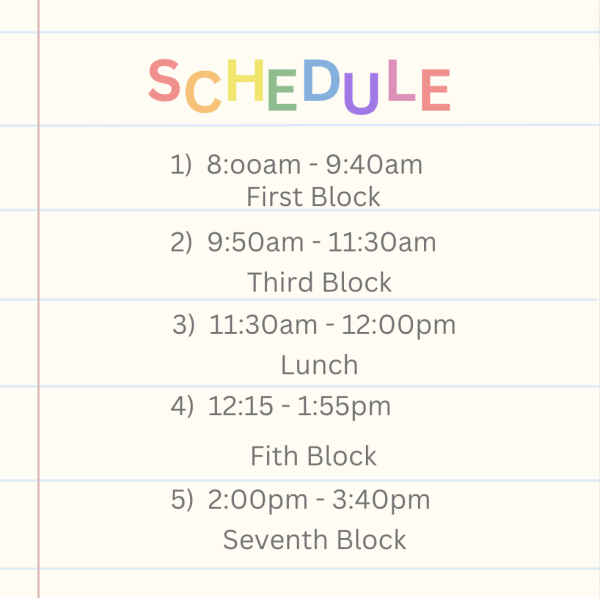

High-speed rail is most ideal for regional distances where flying seems unnecessary but the trip is too long to make by car comfortably. Travel time via plane between Detroit and Chicago is about an hour and a half, not including travel time to the airport or security. The drive is about four and a half hours. The train seems like the perfect alternative. Trains can run faster than cars, and you don’t have to go through the rig-a-ma-roll at the airport. These high-speed systems are widespread on other continents, but not in North America. The Amtrak Wolverine, which runs between Pontiac, MI and Chicago actually travels slower than a car. Taking this train between Detroit and Chicago takes about five hours, providing the train is not delayed. In the four and a half hours it takes to drive between Detroit and Chicago, a train in China can run the distance between Chicago and New York City. The Lake Shore Limited takes about 19 hours to traverse the route between Chicago and New York City.

The climate benefits from high-speed rail can’t be ignored. Most high-speed trains are electric; electric trains powered by renewable energy have significantly less carbon emissions than oil-fueled cars and planes. High speed trains are about 12 times more efficient per passenger than airplanes, not to mention that a single train set can hold around 300 passengers compared to a regional airplane that holds around 100 or less.

Our train to New York City was about two hours late. Amtrak trains are notorious for being delayed. This is mostly due to the right of way on the tracks. Most Amtrak trains run on rails owned by freight companies whose trains get priority over passenger trains. These tracks couldn’t be upgraded to accommodate high-speed rail without the freight companies’ permission. They probably wouldn’t want to have to go through the construction inconvenience unless they were to transition to high-speed rail themselves. High-speed freight isn’t unheard of, but uncommon. Freight tends to be heavy, which doesn’t lend itself to being moved at high speeds. Most freight companies in the U.S. are probably not going to make that change anytime soon. High-speed rail initiatives would have to purchase land and build their own infrastructure, an incredibly timely and expensive process. The Brightline in Florida, which upgraded the existing track, already cost about 7.3 million dollars per mile. The trains would have to have their own track in order to reach the speeds they can in Europe and Asia. This isn’t just for convenience, it is also for safety. Ideally, high-speed trains travel at about 200 miles an hour. Conventional trains run anywhere from about 50 to 90 miles per hour. If a slower train can’t switch tracks fast enough to let the high-speed trains pass, there could be backups or collisions. High-speed rail tracks shouldn’t cross roads either. When a train crashes into a vehicle stuck on the tracks, the damage to the other vehicle can be extreme. Now imagine what would happen if a train going twice as fast were to hit that vehicle. This is an added expense because bridges, tunnels and viaducts would have to be built for new or existing tracks. This isn’t to say that all of the tracks these trains run on need to be designated solely for them. High-speed trains can use conventional track shared with regular trains in order to get to train stations within the cities it services. It’s only once they get out of town that they would transition to the high-speed designated line to make traveling between the cities faster.

The U.S. government passed a one trillion dollar infrastructure bill in the fall of 2021, but Amtrak does not appear to plan to use much of the portion allotted to rail travel for high-speed railways. Instead, they plan to open new lines operating at the same slower-than-car speed. The U.S. will most likely not get the high-speed rail it should solely with the government’s help. The government already has to execute other important initiatives and pay for them. We need a group whose sole focus would be to build and operate the railway in an efficient and ethical manner. There are private initiatives such as Brightline in Florida, but full-privatization of all high-speed networks may not be the way to go. The UK privatized its rail infrastructure in 1993, which led to chaos. Essentially, one private company owned the track, and then other companies would bid for rights to run their trains on that track. The companies running the trains would get a set number of years before they had to renew their contract for those rights. When the contract came up for renewal, someone else could outbid them, and then they would have to remove their trains. This doesn’t mean a private company can’t own both the track and trains, but having the government monitor operations in conjunction with the private company could help make sure passengers aren’t at the complete mercy of the railroad company. There would be more than one voice in ticket costs and services. Perhaps a railroad jointly owned by private investors and the government could work. The federal and state government would still be able to monitor the production, but the majority of the capital could come from private individuals or companies. These private entities would preferably be local to the area the railroad would service so that running the railroad well would be more important to them, in theory. Securing funding wouldn’t have to rely solely on politics.

The U.S. is about 60 years behind when it comes to high-speed rail. The Shinkansen, Japan’s pioneer for the modern high-speed train, was first launched in 1964 for the Tokyo Olympics. Amtrak launched the Acela Express, a high-speed train between Boston and Washington D.C. in 2000, but hasn’t developed another high-speed line since. Having regional systems that can operate at the same speeds as Asia and Europe would be beneficial to the U.S. High-speed railroads in Europe and Asia have made a profit. Even if it fluctuates, it’s still possible. Suppose the government can’t pay for the railroad. In that case, the private sector should, and invite the government along to have checks and balances within the system to ensure that the railways can operate in an efficient manner. If that can happen, America will have a brighter future where the smog is just a thin or nonexistent wisp across the sky.