Unbound Acceleration

As the country’s math achievement gap grows, public schools are questioning where accelerated math programs fit in. But we need them now more than ever.

When I was in sixth grade in 2016, my grade was the most advanced class my middle school had ever seen. When sixth graders were distributed across math classes, a whole class of us— almost a fifth of our grade— went to Algebra I, a class traditionally taken by incoming ninth graders. Some even went to Geometry, the class after that. Teachers shook their heads and wondered at the newest generation: what was happening with these kids? Now, I’m a senior, and my little sister is entering middle school. In her sixth grade class, almost half the kids start in Algebra I. The trend, even within so little a difference as six years, is staggering, and it’s not stopping.

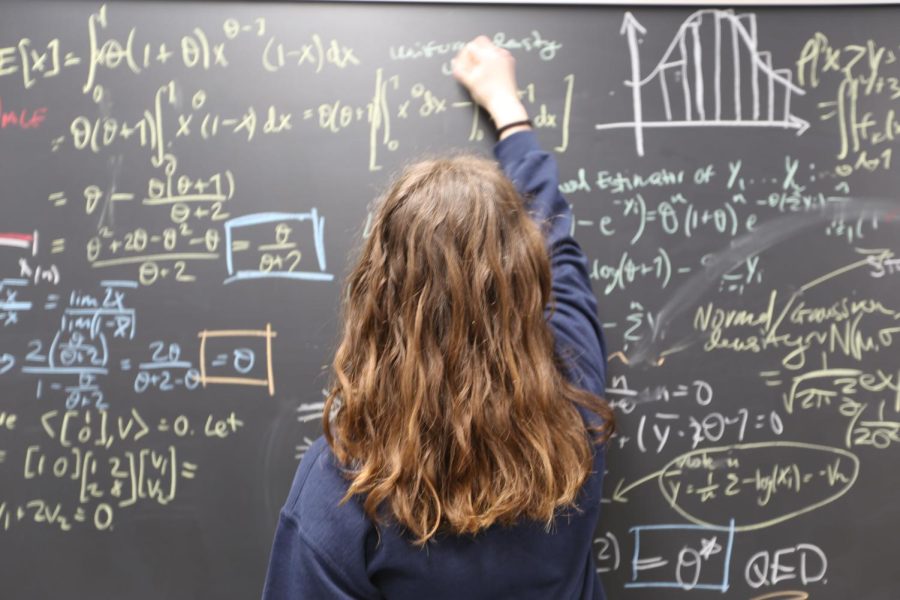

This is because around 2016, right when my sixth grade class was shocking teachers, a shift began taking place in Ann Arbor elementary schools. Fifth graders, instead of a traditional math class, now had the option of learning accelerated math through a virtual service called ALEKS, working on their own with only the occasional proctored exam. If they so chose — and many did — they could steam through three years’ worth of middle school math classes in months: now, they would never enter a middle school math classroom, instead going straight to Geometry or even Algebra II at a high school nearby. These kids circumvented the most common objection that educational authorities like to cite about math acceleration in general and early algebra in particular. They were doing the opposite of parroting back what a teacher said without conceptual understanding: they were teaching themselves, understanding the curriculum at their own pace. That pace just happened to be faster than anyone could have anticipated.

Objectively, this is a good thing! Our children and younger siblings can learn — are learning — math faster and better than we ever did: what’s not to like about that? This is a generation who can learn anything as long as they can find it online, who will take AP Calculus BC and move on to college-level work before any group of kids before them, whose own children and younger siblings might take sixth grade geometry and learn AP Linear Algebra. Their futures are bright.

But their light-speed acceleration is far from universal. And that’s where the problem starts.

We cannot ignore that as with many educational disparities, whether a child is an advanced math student is highly correlated with their background. While AAPS’s precocious ten-year-olds, often with educated parents and a large household income, plan out their ninth-grade calculus trajectories, math students— especially the youngest— as a whole across the country are falling further and further behind, stalled by ill-prepared teachers, ineffective curriculum and years of math on Zoom. Within the country, Black and Hispanic students are underrepresented in top-scoring schools and advanced math programs, as are female students, and the disparity only grows as students get older. Even before the pandemic, our math achievements and scores as a country were dismal, nowhere even approaching the standards of other ‘developed’ countries (and a good fraction of ‘developing’ ones, at that); now, the gap is wider than ever. The top is growing ever-higher, as our middle schoolers are showing us; the bottom is sinking just as quickly from kids being failed by the same system.

Why am I writing about the kids at the top, then? They’re not generally the ones that education legislators and experts are worrying about, after all. They’re not the reason why U.S. math is an international disgrace. But it is programs made for them, and the kids who will become them, who are in danger of becoming the casualties as we try to make math education equally accessible to all.

The math gap can be closed. Why we’re not getting it done is an entirely different question, one of national security priorities and standard of living and educational funding. I’m not writing about any of those; I’m writing about the future of math education as it stands.

So here’s my claim: if we don’t close our achievement gap from the bottom, the system will fall apart.

Let’s go back to our population of AAPS fifth graders, diligently teaching themselves and each other algebra from the beanbags and alphabet carpet squares of their elementary school libraries. Yes, many of them have the privilege of educated parents who will pay their college tuition and encourage math learning at home. The key, though, is that it’s not all of them, and it doesn’t have to be.

We’ve established that there is a real and dire learning gap in math education. Where schools start getting it wrong is when they pin the inequality on the kids who are doing well. Aside from the moral — how anyone looks at a group of ten-year-olds and thinks “how dare they be doing better than their peers” instead of “how can we help the kids who aren’t reaching this standard” is beyond me — trying to stop accelerated math programs in public schools is actively increasing this gap.

You could take the No-Child-Left-Behind approach and teach to the bottom of the class. You could make sure nobody learns anything, treat everyone with perfect equality, and call it equity. But it will never work, because you will be harming the exact demographics who you are so sure you are helping. Public school advanced math programs present an accessibility to learning that no other institution in this country can match; it is a particularly brutal kind of collective punishment to take away accessibility for everybody when the people with privilege never needed that access to succeed in the first place.

Preventing students from accelerating in public school math only means that students — the students who can pay — will find ways to accelerate that do not involve the public schools, leaving their less-privileged classmates to suffer the consequences. These kids are going to be withdrawn and sent to private schools where they can learn all the math their hearts desire. They’ll be sent to Mathnasium and study circles and private tutors. They’ll study from YouTube videos and Khan Academy and MIT OpenCourseWare, whether or not school boards and superintendents think it’s age-appropriate or equitable for them to learn. You can’t stop them. More kids will accelerate in math every year, whether or not the public school system survives to see it.

So that’s about the state of things. Our kids are getting better and better at math, and they’ll keep on doing it if we only let them. Some kids are struggling to keep up, and we should help them. Other kids want to learn math faster than their schools will teach it, and we should help them, too. Whether you like it or not, it’s the modern age: sixth-grade algebra is here to stay.

It’s time for schools to adapt.