Ji Hye Kim was working in a hospital when she came across a study that stated that a person’s level of happiness is determined by who they work with, rather than their family because they actually spend more time with the people at work than with their family. This idea changed the trajectory of Kim’s career.

“I was working 10 to 12 hours a day in hospital management,” Kim said. “I was beginning to realize that if I am going to spend half of my life doing something, I didn’t want it to be something I didn’t enjoy and I didn’t think it was worthwhile. And food gave me joy.”

Kim’s road to the food industry was long and spanned many countries. Learning how to cook was an expensive feat. With the high cost of culinary school, Kim had to seek out opportunities to learn on her own. She started at Zingerman’s working in the prep kitchen; there she learned how vastly different it was to make food for four people versus making it for 40 people.

She then dove into an internship with a famous chef in Madison, Wisconsin, followed by a stint in New York. Finally, her biggest learning came from the Rome Sustainable Food Project, which is a working and learning kitchen in Rome where she spent about six months and got the bulk of her culinary education.

“I worked in different kitchens and created my own curriculum to learn from,” Kim said. “In some ways, I was getting paid for my own education.”

Although each of these experiences enhanced Kim’s culinary skills, none taught her the art of making Korean food. Kim turned to historical cookbooks written in Korean from the 17th and 18th century, vegan cooking, Buddhist cuisine and local Korean restaurants. Due to the fact that she speaks Korean and can read the language, Kim was able to really take all aspects of her learning and bring them to life in her restaurant.

Missing the authentic Korean food that she grew up eating and not finding many options that tasted like home, Kim saw an opportunity to provide home cooked Korean food for the Ann Arbor community.

“I missed the home cooked meals that I was used to from my mother,” Kim said. “I am from New Jersey and in New Jersey, there’s diversity within the Korean restaurant cuisine, whereas in Ann Arbor, the menus are the same. Or similar enough from restaurant to restaurant. I would say we are feeling like we’re filling a little bit of void and like offering something a little different.”

Kim has hand crafted the menu with an emphasis on making each dish unique. She has created plates that remind her of what she ate growing up.

“My favorite dish changes here and there but I think my most favorite dish that I consistently come back to is the rice cakes dish,” Kim said. “I think we offer different versions that are unique. Most often it’s served sort of like a saucy braised rice cake dish with sweet and spicy gochujang sauce. We make the texture a little more crispy and then we have three different flavors. So you can have your pick on which flavor so I tend to go back to the dish a lot. I know the story of the dish. This is also a dish that I used to eat as a child, after school I would get it from the street vendors. We try to incorporate local vegetables and mushrooms into it whenever we can.”

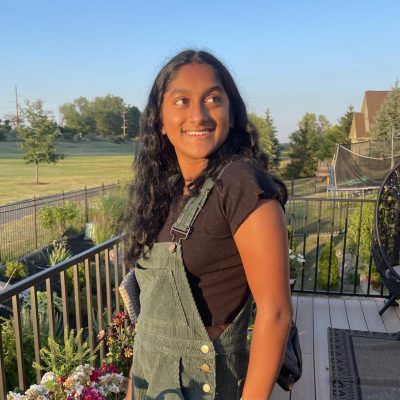

Rani Nathwani, the front house lead, believes that the hard-work Kim has put into curating the menu is shown. The attention to detail and creativity behind all of the food that is made has built a strong sense foundation for the restaurant as a whole entity.

“[Miss Kim] has worked really hard creating all of the different items and doing a little bit of a fusion between different dishes,” Nathwani said. “With the Tteokbokki, the sauce is a lot thinner and the rice cake part of it is more fried. The quality of ingredients is so high. We try to source locally from the best farms and the best places that we can get the best quality of product from and you can really taste it.”

Kim has worked hard to earn a reputation of uniqueness.

“We’re doing a very particular kind of Korean food,” Kim said. “We pay attention to the story of the food and the story of the people who made that food. And that’s I think beyond just understanding like ‘oh my mom used to cook this or my grandmother used to cook this.’ I want to actually know the trajectory of the entire dish, over centuries. And how that dish evolved throughout time and how it plays out when it lands in a different continent, different country in Midwest Michigan with slightly different climate and different seasons. You have to understand the whole arc of the dish.”