The sound of ice skates gliding across the rink echoed throughout while Natalie Serban and her sister stood in front of a vending machine, deciding what to get. Sprite, Coke and Mountain Dew sat on the shelves, but one caught Serban’s eyes, a soda she had never seen.

The sound of ice skates gliding across the rink echoed throughout while Natalie Serban and her sister stood in front of a vending machine, deciding what to get. Sprite, Coke and Mountain Dew sat on the shelves, but one caught Serban’s eyes, a soda she had never seen.

“Dr. Pepper, that’s a weird name,” Serban said.

“You’ve never had Dr. Pepper?” her sister replied.

And from the first sip, Serban has loved the fizzy beverage ever since, craving it daily and this sweet, spiced drink is a constant in Serban’s routine.

“When I go to Kerrytown and there’s Dr. Pepper, and I’m in a chill mood, I’ll get Dr. Pepper,” Serban said. “Dr. Pepper is a subtle drink to have on the side, and I just really enjoy it and crave it.”

Cravings: an intense desire for a specific flavor or texture and can differ from hunger, the brain’s response to the biological need for food.

“Food hunger can be satisfied by any kind of food,” said Tory Fingerle, a registered dietitian. “Cravings tend to only be satisfied by that particular food or texture or flavor that is being craved.”

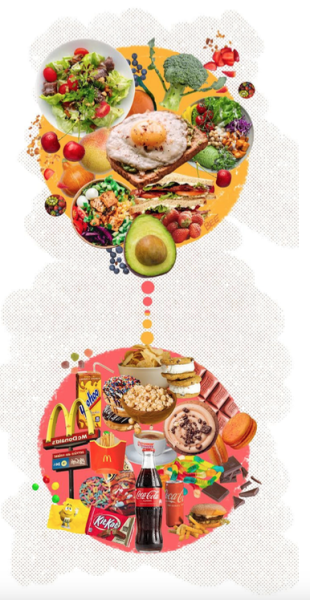

Fingerle has a pool of various clients, from those with nutritional related diseases, like Type Two Diabetes, to those who seek weight loss. Fingerle has seen an array of different cravings, varying in texture and flavor profiles, but there is an evident, occurring theme — the desire for hyper palatable foods, or rich, calorie-dense foods.

A study done by Sheffield Hallam University in the United Kingdom found that people under 25 years old reported more cravings for hyper palatable foods and carbohydrates and those tend to decrease with age. Given that the group studied were young adults, the researchers hypothesized that those in college tend to eat a diet lacking in nutrition or may have changes in taste sensitivity, due to age. But with life comes stress, and food cravings stem from emotions, the environment and hormones. Ghrelin, or the “hunger hormone” is released from the stomach, signaling the brain when hungry. The opposite is leptin: the hormone that indicates fullness. These hormones can be altered, changing hunger levels and cues.

“People who experience menstrual cycles have changes in estrogen levels and estrogen affects your levels of ghrelin, impacting your ability to recognize if you’re hungry or full, and you might crave things,” Fingerle said. “Estrogen definitely disrupts the mechanism because if estrogen is low, then ghrelin isn’t suppressed, and we experience more hunger.”

But fluctuations in hormones are not the sole reason — hyper palatable foods can mess with signaling pathways to the brain, causing the brain to fail to recognize fullness.

“Hyper-palatable foods that you imagine people crave often, so really sweet, really salty, really fatty and calorically dense foods may mess with the signaling pathways of those two hormones,” Fingerle said. “So, we don’t recognize when we’re full and then we continue to crave those foods.”

There are external cues that can influence cravings, such as environmental factors, like commercials and billboard signs, or simply walking past the kitchen or the aisles of the grocery store. Habits, such as nighttime routines, are also contributors.

“It could be a habit of you sitting down, turning on the TV for a couple of days in a row and when you did that, you had something sweet,” Fingerle said. “The fourth day you do that you sit down, you turn on the TV, all of a sudden you’re like, ‘oh, I’m craving something sweet’ because it was from that habit.”

Contrary to external cues, internal cues, including stress and other emotions, exacerbate cravings. Kent Berridge, a professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, observes that many people tend to self medicate during difficult times, leading to binge eating disorders.

But even happy stresses can promote cravings, such as getting a good grade or the job you want.

“There are mechanisms in the brain that we understand a little bit about that accomplish these stress systems when they’re activated,” Berridge said. “They amplify that dopamine craving system, that dopamine wanting system, so it responds more powerfully.”

Whether one craves salty, savory foods or has a sweet tooth, there is no sufficient evidence that people can be predisposed to certain cravings, nor that cravings stem from nutritional deficiencies.

“There are plenty of people that eat a nutritionally balanced diet that still experience food cravings,” Fingerle said. “There is no research that there is a genotype, depicting that one is prone to have specific cravings.”

But there are many hypotheses rooted in the idea that cravings could be based on childhood foods and what one grew up eating or years of restrictive dieting.

Infants who are fed sugary, soda-like water, to relieve pain, can go on to have higher sweet preferences. Conversely, infants were fed a commercially available infant diet, which are bitter by comparison to milk, but infants don’t seem to mind that bitterness, and they go on to have greater likings for foods, like broccoli and spinach.

“Early food exposures shape our tastes and cravings and lead us either into sort of a healthy eating path or unhealthy eating path,” Berridge said.

And restricting certain foods that may be deemed as ‘unhealthy’ can also heavily impact cravings.

“‘I’m not ever allowed to eat candy’ for whatever reason, and then that can intensify their cravings for that particular food because they’re depriving themselves of it,” Fingerle said.

To Fingerle, there’s a harmful connotation surrounding cravings in society today.

“People definitely see them as something they should feel guilty about, but we don’t have to feel guilty for feeling hungry,” Fingerle said.

With Fingerle’s work, she aims for her clients to recognize and understand that cravings, just like any other emotion, such as anger and stress, are not emotions that need to be avoided or ignored. Rather, it’s critical to focus on how to address the cravings.

“How do we kind of experience them? What are our mechanisms for moving through them in a healthy way just as you would with stress or you would with anger?” Fingerle said.

What Fingerle suggests is for people to sit in that craving and experience it. This feeling can be new and uncomfortable, but Fingerle asks her clients to consider questions regarding their hunger and satisfaction levels. She refers to it like a simple, easy-to-follow road map:

“If I’m hungry, is the craving the only thing that’s going to satisfy me right now, or is it any other food?” Fingerle said. “If you’re feeling like that craving is going to be the only thing that satisfies you, I like to say eat what you want, add what you need.”

“Eat what you want, add what you need” is an intuitive-eating practice where you add a food, with protein or fiber, for example, to be more nutritionally balanced.

“Maybe you have some chocolate and you have a few carrot pieces or some fruit or some protein,” Fingerle said. “So you’re making this balanced experience out of it.”

Giving oneself full permission to make certain food choices is another aspect Fingerle emphasizes. When people have deprived themselves of a specific food, overeating and binge eating episodes are common, resulting in more guilt. There’s a way to achieve a nutritionally balanced diet while still enjoying foods one loves without restricting or cutting out certain foods or food groups, like carbohydrates. As Fingerle promotes, mindfulness is key.

“If they give themselves permission, like ‘I can have some of this and because I’m giving myself permission’, I’m not going to feel guilty about it,” Fingerle said. “There’s a positive reinforcement cycle that’s happening.”