Inclusive, equitable, and accessible. These were the principles that fueled the University of Michigan’s approach to emerging generative artificial intelligence (AI). In the fall of 2022, software like ChatGPT started to become widely available. Educators and administrators all over the country had to decide how to respond to this new technology.

Ravi Pendse is the vice president for information technology and chief information officer for U-M. Pendse worked with Provost Laurie McCauley in Dec. 2022 to appoint a faculty committee that would propose an approach to generative AI for the university.

“We should not be talking about banning,” Pendse said.

Pendse compared banning the use of generative AI to banning the use of calculators. U-M quickly decided that this would not be their method. Some New York schools had already banned AI but U-M was looking for another option.

“Our public school students are not just competing with other Ann Arbor public school students,” Pendse said. “They are competing with New York public school students. They’re competing with Boston students. They’re competing with students in China, students in India, students all across the world, right? All of these countries and all these communities are actually using these tools.”

Pendse and the university committee determined that rather than imposing a blanket ban on generative AI, allowing the U-M community the autonomy to discern how best to leverage this technology would be more beneficial. They believe that empowering individuals to make informed decisions fits a thoughtful and measured approach and avoids placing their students at a disadvantage in a rapidly evolving digital landscape.

Bob Jones, executive director of emerging technology and support services at U-M, is a member of the leadership team for generative AI at U-M. As an Ann Arbor parent who attends events like Pioneer football games, Jones sees an opportunity for AAPS to work with U-M to adapt their approach to generative AI in schools.

“Sometimes I volunteer to be on the chain gang and look and I see the Big House there and it’s 150 yards away but I’m not sure that that geographical proximity represents the partnership that it could,” Jones said.”We are enthusiastic about the potential for collaboration and eagerly welcome discussions with AAPS administrators that could lead to endorsing and possibly even encouraging the integration of our platform within the Ann Arbor K-12 system.”

The generative AI platform that Microsoft and U-M developed is called Maizey. Developed with inclusivity, equitability and accessibility in mind, Maizey allows members of the U-M community to use generative AI safely and productively.

To ensure user safety, Maizey does not share prompts with third-party vendors. All uses of their GenAi platform are secure and private. The information and privacy of the U-M community is respected. Any data or questions entered are secure within the platform. At a time when there are many online privacy concerns, securing Maizey was vital to trust within U-M.

“I think we should be highly concerned and we should be paying much closer attention to our data and privacy at the governmental level,” Jones said. He does not feel that AI is something to be scared of, but that we should always be mindful of our online presence and how we share our personal information.

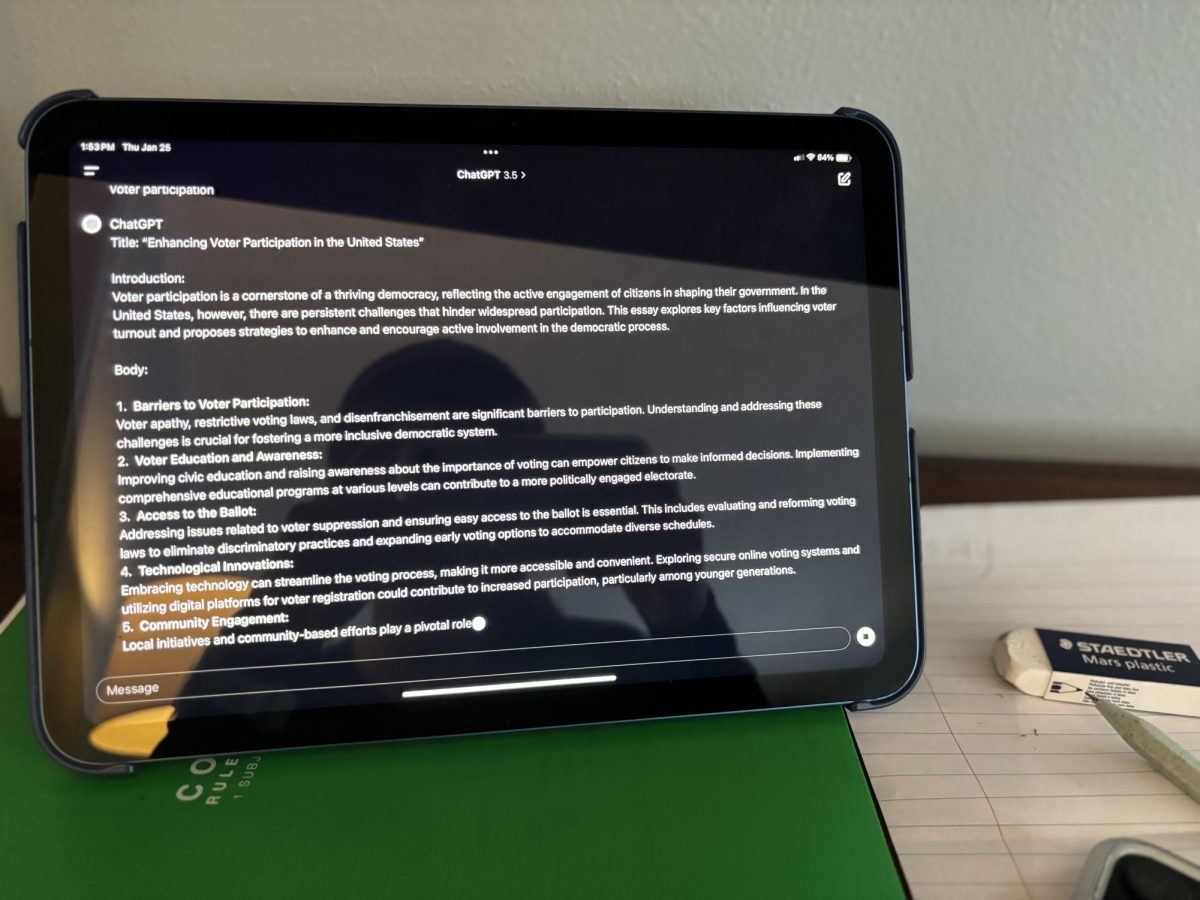

Another known risk of generative AI use in education is academic dishonesty and cheating. This was the main concern school administrators felt they were addressing by banning AI use when these tools started to become widely available.

“This would require training, but I would take a look at how we’re measuring student outcomes and promote the use of AI where appropriate,” Jones said. “I think the risk of AI detection software is that it’s never 100% and I think you potentially put yourself in a position where you don’t have the information appropriate to make any accusations or infer whether somebody used AI or not. It’s an imperfect solution to the problem.”

Traditional methods of measuring student progress such as in-person written exams do not allow for the use of AI. Knowledge demonstration has become increasingly virtual. Although there are benefits to this such as immediate feedback, a more communicative approach would help reduce schools’ concerns when it comes to academic dishonesty.

AAPS, and more specifically Ann Arbor Virtual Academy (A2V), have implemented AI detection tools such as Turnitin. This program analyzes typed essays to try and identify the use of AI. Embedded within Schoology, the process of turning in a virtual assignment is long and complicated.

Banning the use of generative AI in education has another, larger consequence for student outcomes.

“AI is never going to replace humans,” Jones said. “Humans will always be in the loop but humans that use AI really well will replace humans in the workforce that don’t use the tech. Educating youth on how to use the tools available to them can increase their earning potential and improve their outcomes in the classroom.”

“It was very important for us to think globally but then act locally,” Jones said. The goal of public higher education is to prepare students for success in a diverse and evolving workforce. Generative AI is a tool that can aid in this process, but there are equitability issues.

Programs such as ChatGPT can cost upwards of $20 a month to use. In a world where the average annual household income is around $12,000 globally, all students can not be expected to pay for this software, and therefore they lose out on an educational advantage.

Maizey is free to the U-M community. Equitability was a crucial criterion in its development to ensure that all students have the best educational opportunities possible. Accessibility was another critical factor that U-M addressed by making Maizey compatible with screen readers.

U-M has proved that the use of AI in education can be equitable, accessible, and inclusive, just as they set out to. While AAPS has limited academic dishonesty, U-M could be a partner in developing a more empowering approach to the use of generative AI in K-12 education.

Pendse acknowledges the caution exercised by public schools and expresses a genuine willingness to offer assistance, should they desire it.

“I would recommend a thoughtful approach where we avoid outright bans and instead empower students and faculty to use these tools responsibly,” Pendse said. “By collaborating and sharing experiences, we can all grow together. After all, AI programs are designed to complement, not supplant, the creative spirit that drives educational innovation.”

Generative AI doesn’t have to interfere with student learning. It can be used as a tool and in a limited capacity. U-M has successfully launched Maizey with no negative impact on student outcomes.

“What [generative AI] does really well is handle transactional work that’s repeatable,” Jones said. “It can even templatize the big picture thinking but it has no creativity. It has no human voice or human touch. Using AI as a classroom tool would not impact developing independence or executive functioning skills because it cannot replicate the curiosity of a human child.”

“My advice is to become masters of the technology of generative AI,” Jones said. “Why be a violinist or a percussionist in an orchestra? Embrace generative AI and become the conductor and let it work for you for something much bigger.”