In the heat of summer, Moose Gultekin recognized a red flag, witnessing a car back up into a stop sign. Deciding to knock on the car’s window, they saw that there were needles in the passenger seat. Gultekin promptly identified the situation as an overdose and called 911. Gultekin defines this as one of two situations that made them consider how many people really know what, when and how to use naloxone.

“It’s one of those things that has always been a huge proponent of harm reduction,” Gultekin said. “Things like needle exchange, safe injection sites and naloxone need to change. We criminalize people with illnesses like substance use. It’s an issue in which it’s a disease that needs to be seen and treated, but instead, we’re criminalizing these people that need our help.”

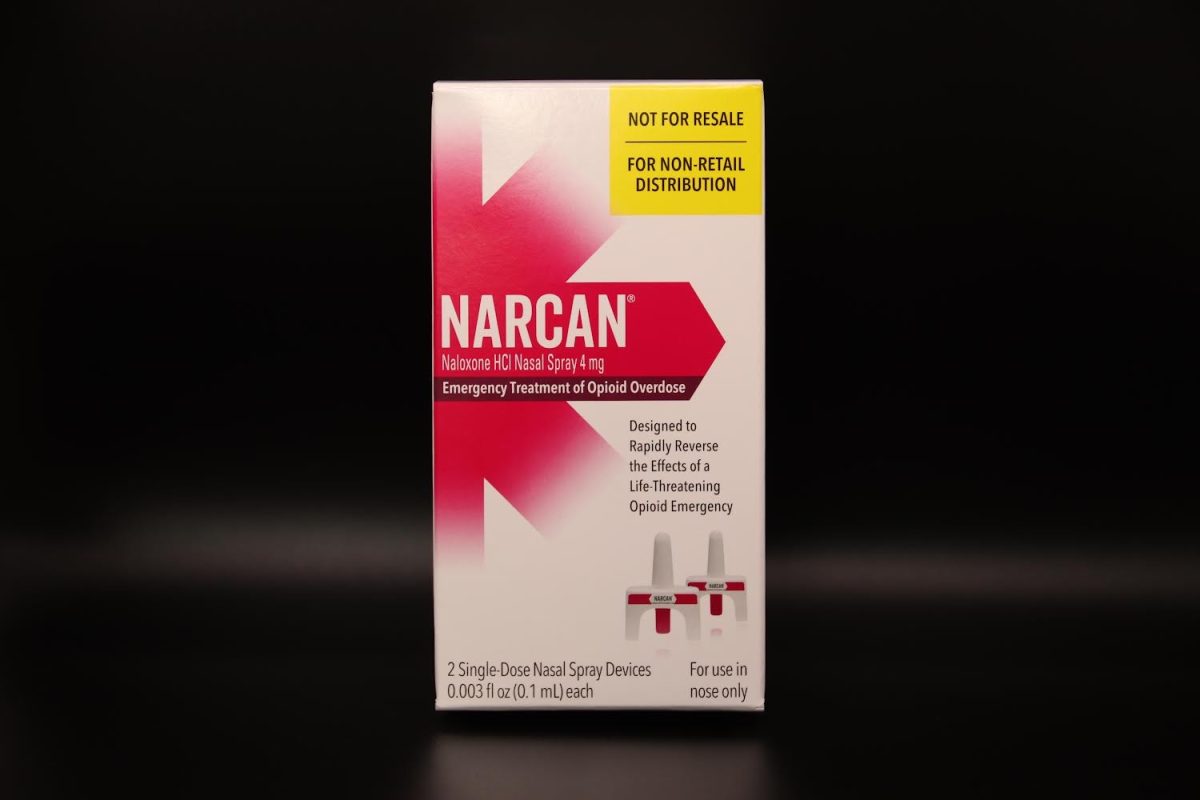

Naloxone, a nasally or intravenously ingested drug, works by attaching to the same receptors that opioids do, effectively blocking and taking them off of the receptors.

“It stops an overdose immediately,” Gulketin said. “It has no negative side effects aside from coming down from your high really fast, which means you’ll experience withdrawal symptoms.”

Now, Gultekin wants to make a change. On April 10, Gultekin along with Becky Brent, a health teacher at Community High, and U of M’s OPEN (Overdose Prevention Engagement Network) provided a special opportunity for Community High’s students. They are getting Naloxone into their own hands, making sure they know how to use it, what to do with it and how to respond in emergency situations that might involve naloxone.

“Somewhere between 15 and 20 students attended,” Gultekin said. “I know that we did it on a day where not a lot of people were around and it was also not a required thing but if more people are interested in this training or just figuring out what naloxone is, we would absolutely be willing to hold more training sessions, especially next year if people are interested in it.”

When considering the usage of naloxone on an individual, you will want to look for a few indicators that this person has indeed overdosed and is in need of naloxone.

“There are three major signs that you look for when someone is overdosing,” Gultekin said. “That is shallow or Labored breathing, unresponsiveness to pain and extremities getting significantly less blood. So you start to see blood loss in the fingers and lips so bluish or grayish lips and fingernails is where you will like to look.”

While it can be very simple to observe someone breathing shallowly and experiencing blood loss in their extremities, it can be challenging to determine whether or not someone is sensitive to pain. Gultekin recommends a method called the sternum rub.

“You take your fist and rub your knuckles along the sternum. It’s really uncomfortable and it hurts really bad,” Gultekin said. “Most people will react to it in pain or discomfort. So, if they’re not reacting to that or they are unconscious, that’s a problem.”

Gultekin notes that even if there’s a chance that the individual is not overdosing and doesn’t require naloxone, you can still apply it.

“There is no downside to giving someone naloxone,” Gultekin said. “Before you give naloxone, 911 is step number one. You let them know where you are, that you think it’s an overdose and that you’re going to give naloxone.”

Properly taking care of an overdosing individual with naloxone is quite simple. First, you take naloxone out of the package and put it up to the individual’s nose. There is no need for a test spray as it only sprays once. Once you’ve sprayed it up their nose, that’s it for the naloxone. After that, all you have to do is keep the 911 dispatcher updated on what’s going on and what you’re doing. After those two steps, the next best thing is to put them in recovery position, check if they’re breathing—and if not—perform CPR every 3-5 minutes.

Gultekin recognizes that many people are concerned about laws in Michigan; however, there are regulations that specifically protect minors from being in possession or in an emergency requiring medical assistance.

“Even if you are not a minor, the likelihood that you will ever be charged with possession if you are around someone who is overdosing is extremely low,” Gultekin said. “In those circumstances, our EMTs, police, and firefighters all understand that the person who is dying is more important than any possession charges.”