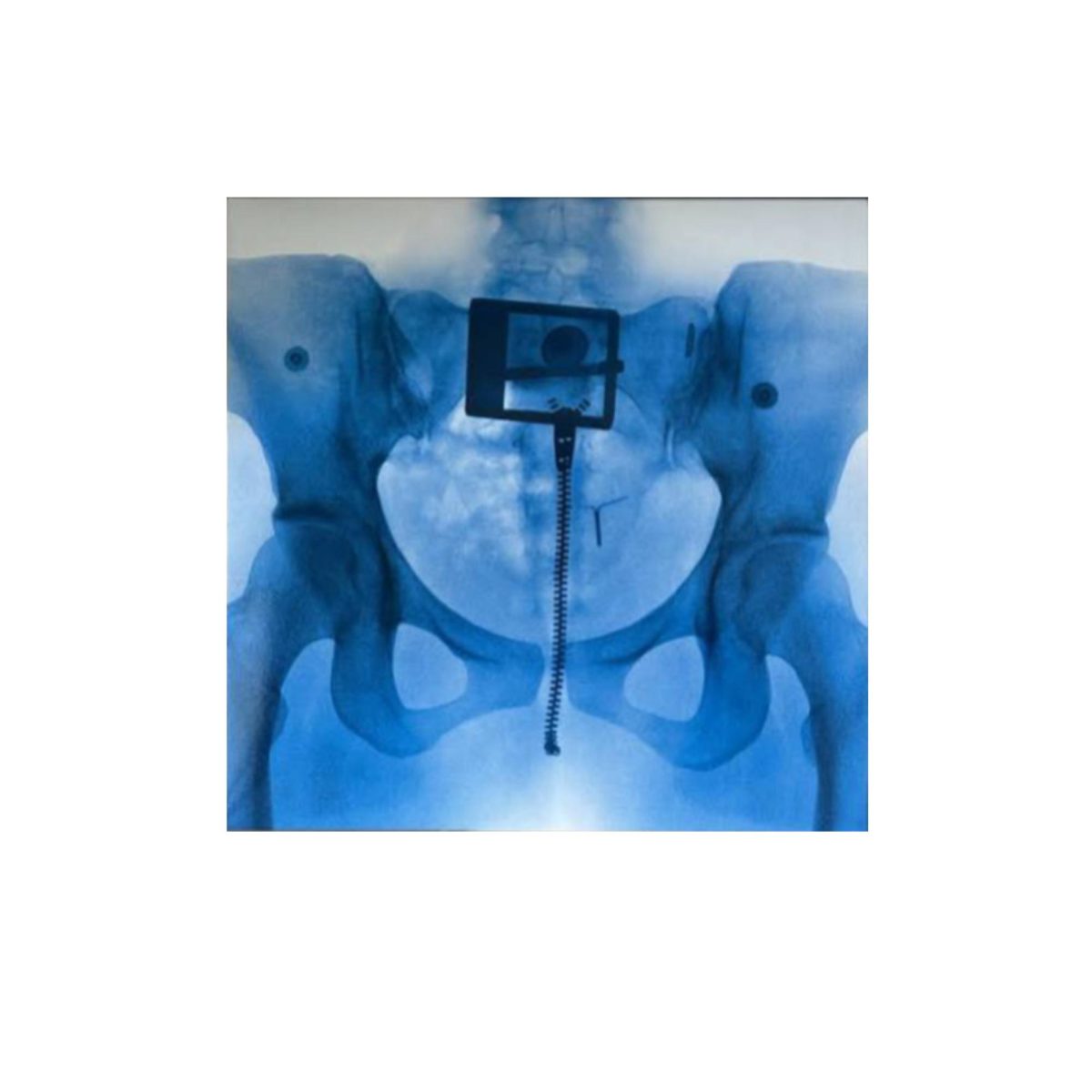

The opening scenes fade in, slow enough for any viewer to take its information to heart, a clip of a newspaper that reads a title deemed shocking for its era — “Suicide Rate High Among Gay Teens”, the story reading an upsetting statistic: 30% of teen suicides are done by such a small, marginalized group outside of any other context.

Produced in 1993, the title itself feels robotic and distant. In 2024, above 41% of LGBTQ+ youths have considered suicide once in their lives according to a survey held by The Trevor Project, anti-LGBTQ bills. As far as we had stepped forward in support, it felt as though the swinging of a pendulum went back rapidly–making the story still relevant, tragically, to this day.

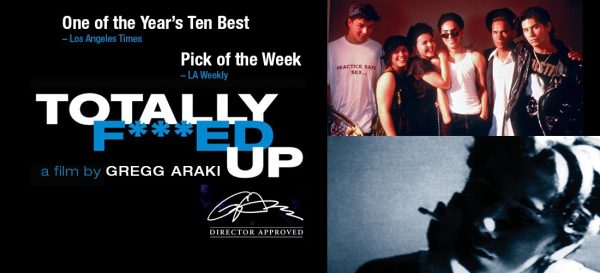

Visually, the film works as a unique piece of art, differing from other works done by Gregg Araki, its director. A mockumentary shot using guerilla style, for example, handheld cameras pointed at the group of 6 we follow throughout the story. This approach to “Totally F***ed Up” and “Nowhere” later vanished from the final film in its Teenage Apocalypse trilogy and other later works. Araki Described the film as “a cross between avant-garde experimental cinema and a queer John Hughes (of ‘Breakfast Club fame’) flick.”

At its core–it’s about togetherness, how unchangeable situations bring people together and the tragedy behind that, behind feeling different from even people you should feel a connection to, politically it is an expression of rage, a rage against indifference.

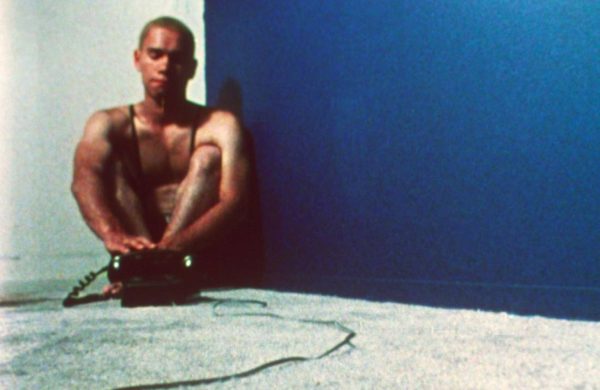

The color itself makes its Los Angeles setting feel alien. It’s rare and infrequent scenes shot in the light–glowing blue skies, matching paved pools with darker grasses framing your vision. Night takes over in the film, the neon lights of L.A. with side streets, it almost lacks its glamor in public shots, satire of the 90s club scene at its time, it feels post-apocalyptic: endless drifting through a climate of hedonism and empty parking lots, human conversations placed underneath bright inauthentic billboards, a symbol of rejected commonality between the main characters.

The stereotypically L.A. vocal fry becomes a noticeable contrast with the interest in togetherness and emotions. They sound vocally unimpacted and robotic from anything around them until it becomes too late.

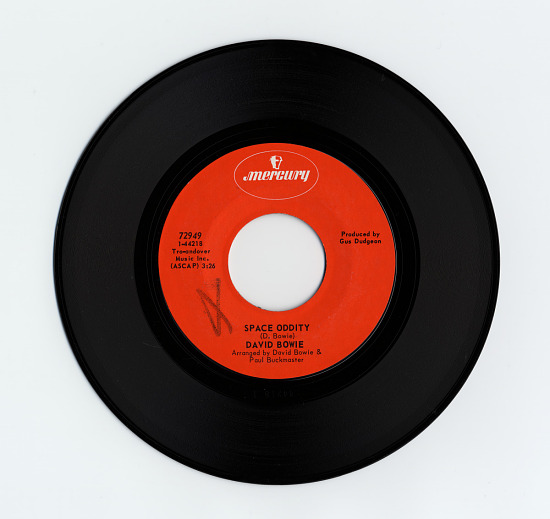

The soundtrack is filled with shoegaze and slowcore icons like Pale Saints, Red House Painters and The Jesus & Mary Chain. The main character, Andy, played by James Duvall, a recurring muse in Araki’s work, often sports a shirt from the 80s industrial metal band, Ministry. Music remains prominent in the story, from the darkened club scenes to its more drone rock-influenced soundtrack, music that was equally a product of its time as the rest of its storytelling.

It follows a rag-tag collective, each of the 6 characters feeling symbolic of the early 90s counterculture and its cautionary tale, the mockumentary style falsely recorded by character Steven, creating an accurate conversation between fictional early-adulthood-late-adolescent characters. Despite the narrator being significant, the most critical character who stuck out as a secondary story is Andy, a depressed and reproving figure in the story which creates a contrast between a slightly more vapid cast and his search for any sign in this world of love. Uptight about all things love, he’s the opening face of the film, smoking as the director, Steven’s voice begins and adjusts the camera.

The other character, Tommy, an immature figure that immediately contrasts the dark and brooding character of Andy, presents himself on the screen in a similar fashion to a confessional in reality TV, a static noise lightly heard in the background, this is not supposed to be professional.

Michele and Patricia are fun loving and retrospectively two of the most positive characters. Unfortunately the characters consist of the most shallow in its writing, using them as comparisons of a healthy couple or for mentor-like advice for Steven and Deric, an introspective and nervous individual going into college. Everyone, besides Steven turning the camera on himself, unframed and reaching for it every few seconds.

This film, notably identifiable to the name, is not intended for a younger audience. It wasn’t necessarily a blockbuster hit when it was released for a reason, plenty of lines haven’t aged the best, but then again, each number flashed on screen with static blue lights shows a new topic; drugs, society or love. But it’s not something we should necessarily avoid. It shouldn’t feel awkward to talk about AIDs or sex, and that was what was entirely intended in this film, whether through a breaking of the fourth wall with a character director, affected by such things or Araki himself witnessing this in the early 90s himself.

Besides it’s harder to watch topics, the plot itself is where the film shines through, diverting into four plots entirely. Each plot, much like the rest of his films, feels tense and uncomfortable, yet not negative. This isn’t a thriller-action movie, this is just with each watch, more and more foreshadowingand building up to a tragedy in the making. Each one feels like a different take on love. Steven, the director, describes his love life with Deric as “a mutual terror of loneliness,” while characters like Tommy claim to fall in love “every 15 minutes” and the direct opposite, Andy claims “love does not exist.”

As I look back at a film, I hesitated initially to watch over 3 years after my first viewing. I have never let a director change my opinions on my life goals and taste in film more than Gregg Araki. If you’re looking for a good introduction to LGBTQ+ cinema that is direct and unapologetic, this film is calling you.