I don’t care about gun violence.

At least, that’s what my reaction — or lack thereof — might suggest. When news breaks of another shooting, my response is limited to a clenched jaw or a momentary dropped stomach before I return to worrying about tomorrow’s homework or next week’s big game. In a world where violence feels like the baseline expectation, I have learned how to compartmentalize our seemingly regularly scheduled tragedies.

This apparent apathy isn’t disinterest, but rather a wall I’ve built, brick by brick, bullet by bullet, creating a sense of emotional distance, no matter how false it may be. I ran right into it at a recent high school dance. A balloon popped, and I watched as a crowd of glittery heels and slightly sweaty dress shirts instinctively tensed, scanning for exits. For a moment, everything was quiet. As the realization sank in that it was just a balloon, shoulders dropped and dance circles re-formed, but one thought stuck in the back of my mind: in the case of actual danger, there was almost nothing we could have done to protect ourselves.

I thought back to freshman year, sitting in the car with my mom: the white leather seat sticking to my thighs and the green fabric of my backpack resting against my shins as she told me about a shooting at a school barely 80 minutes from mine. Four students died at Oxford High School — though it’s telling that even despite its proximity and relative recency, I had to double-check the school’s name. There have been so many incidents like it that they have blurred together in my mind, each new tragedy layering over the last like sediment, building the foundation of our new normal.

This pattern of violence extends far beyond school walls, threading its way through every aspect of American life. On Dec. 4, 2024, Brian Thompson, the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, was fatally shot outside the New York Hilton Midtown Hotel in Manhattan. Less than a month later, on Jan. 1, 2025, Shamsud-Din Jabbar, a 42-year-old army veteran inspired by ISIS, drove a rental truck into a crowd, killing 14 and injuring 57 in the process, before being killed in a shoot-off with police. Each incident adds its own brick to the wall of desensitization.

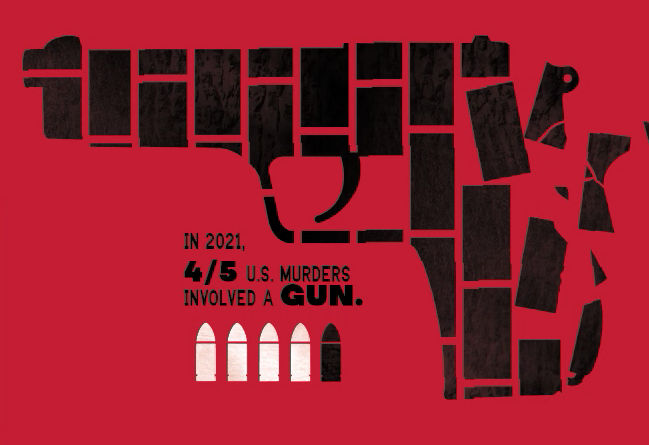

The statistics paint a picture of an American crisis. According to the Pew Research Center, about four in five U.S. murders in 2021 involved a firearm — the highest percentage since at least 1968, when the CDC’s digital records first began. Moreover, more than half of all lives lost to suicide in 2021 involved a gun — the highest percentage since 2001. Since 2019, we have seen a 23% increase in gun-related deaths, with a gun-murder-related spike of 45% during the pandemic.

As a nation, we’ve created a culture of destruction. According to The Gun Violence Archive, “mass shootings are, for the most part an American phenomenon.” We’ve normalized the unthinkable, routined the horrific. This way of being isn’t new, it isn’t some outlandish theory; it’s the way we are. But it doesn’t have to be.

The reality is that guns have become more constitutionally protected than my ability to make healthcare decisions. We live in a world where the opening of a bag of chips in a cafeteria could trigger panic, where mental health resources remain scarce while access to weapons grows easier, where socioeconomic status and race influence both the perpetration of violence and the way we respond to it.

I live in a world where, in order to protect myself, I have to build walls to block out the lurking thoughts of bloody backpacks and empty desk chairs. They allow me to function in a world where my classmates are simultaneously keeping up with algebra homework and updates about the latest school shooting.

But here’s the thing about walls — they don’t just keep pain out: they keep us trapped in a cycle of inaction. It’s time to stop accepting this as our normal. Each brick we lay to protect ourselves unintentionally becomes an obstacle to change. It’s time to tear them down and feel again, fully and deeply, even though it will hurt, because that’s what it will take to finally create change.

The truth is that I shouldn’t have to publish a piece like this. No student should have to develop coping mechanisms for recurring violence. No teenager should know the best hiding spot or fastest way out of their chemistry classroom. No child should have to distinguish between a popping balloon and a gunshot.

And yet, here we are. Until we decide that the well-being of our children matters more than an individual’s ability to possess a weapon, this will remain our reality. The question isn’t whether there will be another school shooting — it’s whether we’ll care when it happens.