The documentary called “Waiting for Superman” has brought a lot of publicity to the public education system, its flaws, and how it can be improved. At the screening I attended in the Michigan Theater, which was followed by a discussion session with a panel of education experts, the main theater was packed. Even before the movie began, it was clear that public education is a sensitive topic to many: teachers, administrators, and school principals made up a large part of the audience.

“Waiting for Superman” told a compelling story. It was centered on five children, four of whom were impoverished, intercity minorities living in Los Angeles, New York City, and Washington D.C. They each had parents who were concerned about their child’s education, and who were searching for an alternative to the local, low quality public school. Eventually, these parents found charter schools with good reputations to enroll their children in but because the limited spaces were assigned by lottery, only one student was accepted.

This narrative was interspersed with interviews featuring Michelle Rhee, the former chancellor of Washington D.C. schools, Geoffrey Canada, founder of a charter school called the “Harlem Children’s Zone,” and other education reformers. They gave the “down-and-dirty” on what they believed was wrong with public education in America and how it can be fixed, aided by infographics galore.

As the movie ended and discussions began, the belief that steps need to be taken to improve education in America seemed to be the only thing everyone agreed on. The movie discussed obvious problems such as failing schools with abysmal graduation rates, called “dropout factories,” and the achievement gap between white and minority students. But when it came to finding solutions, discord abounded.

One controversial suggestion promoted by “Waiting for Superman” is the expansion of charter schools. Charter schools are privately run but publically funded, and by law must use a random lottery to accept students. Charters are more independent than public schools – they employ their own teachers and administrators – and proponents argue that this makes them more effective.

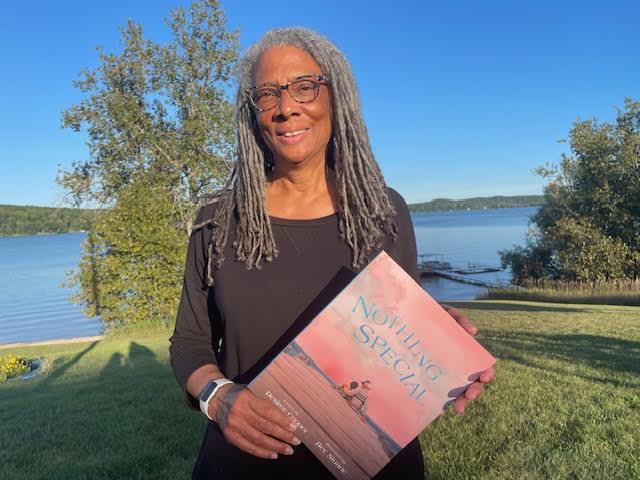

Susan Dynarski, an Associate Professor of Education and Public Policy at the University of Michigan, has done extensive research on charter schools. During the discussion session after the movie, she explained the results of her research on charters in Massachusetts. “The effects that we measured [in these charter schools]…are larger than any intervention I’ve ever seen in education.” Dynarski collected data from charter schools that taught mostly minority students, and found that “Two, three, four years in one of these schools was erasing the achievement gap between blacks and whites, between Hispanics and whites…We’ve got something where we don’t know why it works, but we do know it does work.”

But other panelists argued that, though improvement is necessary, the public education system is not fundamentally broken, and that a dramatic shift to charter schools would be uncalled for. This position is reinforced by a statistic briefly mentioned in “Waiting for Superman”: only 17% of charter schools have academically performed better than similar public schools.

Bob Galardi stands for a different kind of public school. A former dean of Community High, he worked for Ann Arbor Public Schools for 31 years. He is now an educational consultant for the Institute of Student Achievement (ISA), an organization based in New York City that works with struggling school districts to create small, independent public high schools. Specifically, he is helping the Detroit Public Schools with four recently opened ISA schools.

“The interesting thing that anybody at Community would like to know about is that these schools are based… solely on a model that looks like Community,” said Galardi. “I mean exactly. They have distributive counseling…which is forum, there is no separate curriculum, all students are expected to go to college, and they’re not to be enrolled beyond 400 to 450 students.” And, like the dean at Community High, principals at these schools have more authority and freedom to do things differently. “These are all research based principals for creating great schools,” Galardi added.

Another hot topic brought up in “Waiting for Superman” was the need for improvement in teacher quality. The movie asserted that teachers are the most significant factor in a student’s education, because all kids can learn under the right circumstances. According to the movie, a bad teacher can manage to teach as little as 50% of subject matter for one year, while a good teacher can squeeze in as much as 150%. The conclusion drawn from this is simple: teacher quality must improve, whether by firing bad teachers, instituting alternative forms of compensation, or providing more professional development if education is to improve.

Those on the discussion panel following the movie accepted this notion with more than a few grains of salt. Michael Flanagan, the superintendent of public schools in Michigan, argued that administrators also play a large role in shaping a public school, saying, “It’s old research that principals and superintendents make the difference.”

Bob Galardi agreed with this critique. “The problem with ‘Waiting for Superman’ is that they made teachers seem like superpeople, but teachers fit into a whole system,” he said. “If a system is effective, marginal teachers get better when they work around good teachers.”

Regardless of how data is interpreted or issues debated, the fact remains that education is as important as ever. “Waiting for Superman” pointed out that in the last 30 years, America’s education system has fallen behind those of many other developed nations in reading and math, even as U.S. educational spending has increased. According to Bob Galardi, this trend is not sustainable in today’s economy. “In this transition we’re going through from an industrial economy to a smart economy, a technical economy. We have children that won’t have a place, if they don’t learn. There’s nowhere.”